OUR HISTORY: The Murray Darling floods of 1956 were one of the worst disasters in our state’s history. Greg Barila spoke to several South Aussies who remember the year the rivers rose up.

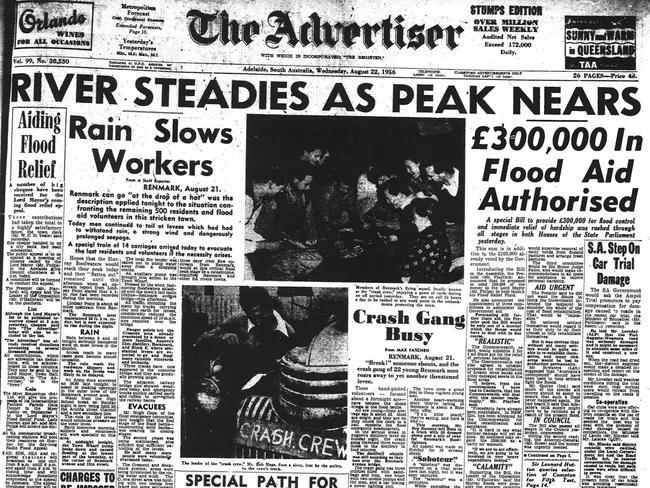

The “Great Flood” of 1956 was the worst on record and an event described as “the greatest catastrophe in the state’s history”.

The disaster displaced thousands of people, wiped out crops, crippled local industries and left a damage bill in the millions of dollars.

The flood was the culmination of a La Nina that began in 1954, bringing heavy rainfalls in Queensland, Victoria and NSW through until the first half of 1956, filling not only the Murray, but the Darling, too - a rare event.

The rivers joined forces at their junction in Wentworth, NSW, and from there, there was only one way for the water to go - down to SA.

The Murray would peak at 10.2m in Renmark and a staggering 12.3m at Morgan.

Some areas reportedly were flooded up to 100km from the normal flow of the river.

The water almost touched the first floor balcony of the Mannum Hotel and rose to nearly the same level down the street at the Pretoria.

According to Riverland author Graham Irwin in his book A brief history of Barmera, at the height of the flood, in late August, the river and Lake Bonney “merged to form an unbroken sheet of water, stretching from Barmera to Moorook” - 17kms away.

The Big Wet impacted on ordinary life in unexpected ways.

As local historian Alison Painter later wrote: “One side-effect of the floods was reported from near Meningie where a dairy farmer killed 1032 tiger snakes driven on to his property from their normal swamp habitat as the waters spread inland.”

But the people took on the water and won.

For months on end, from the time the alarm bells started ringing in early May, communities up and down the river worked 24/7 removing logs from the locks, filling sandbags, building levees - anything to hold the water back.

Command centres were set up and “crash gangs” - teams of young men, with trucks stacked with sandbags and emergency equipment - were put on standby to respond quickly when the river, inevitably, broke its banks.

Volunteers patrolled the banks under hurricane lamps using phone lines laid by the army.

“By early August, more than 300 men were engaged on flood work in the Barmera/Cobdogla area, together with 50 tractors and scoops, 5 dozers, 5 front-end loaders and 35 trucks,” Irwin wrote.

It was, he wrote, a time of “organised confusion, with predicted levels being changed almost daily. It did however create a unifying force in the district that had not been evident before, or since.”

COBDOGLA

YVONNE “Vonnie” Fletcher was 34 and running a trucking business with her husband, Syd, in Cobdogla when rising river levels put the town on a defensive footing.

“We were taking all our good furniture up to places out of the way where the flood wouldn’t be reaching,” Mrs Fletcher, 94, says.

“We still lived there but most of the good furniture had gone and carpets rolled up, things like that.”

“The Cobby (Cobdogla) school kids were bussed off to Barmera every day.

“Most of the elderly ones went off to live somewhere else so there weren’t so much worry to be looking after them.”

She says there was a general sense of worry across the district.

“Everybody was very concerned about it because had the bank broke that was in front of our house we’d have had about four or five feet (up to 1.5m) of water through it.”

“They built the levees around a lot of the fruit blocks, trying to keep the water out, but I think in hindsight they did the wrong thing because a lot of those blocks were not much good afterwards, because they got so salty.”

Mrs Fletcher, now of Barmera, says while mostly men were at the frontline of efforts to protect the town, the women, too, instrumental.

“The women all along (the river) used to take afternoon tea, morning tea, out to all the fellows that were building the banks.

“And I used to have to go down to the pumping station and see what the measurement was and ring and let them know.”

“Also around our area, there were three different sections, with one person in charge of each section in building the banks and I used to write articles in for the (Murray) Pioneer on what was being achieved with each section.”

Mrs Fletcher isn’t sure “catastrophe” is the right word to describe what happened 60 years ago.

But she says one thing’s clear - the 1956 flood was a once-in-a-lifetime event.

Every few years there’d be smaller floods but never like the 1956 one.

“I’ve made a book about my life, and only just a little while ago I was flicking through it and came across a few pictures of us rowing a boat on what was the Cobdogla Bowling Club.

“I don’t think we’ll ever see it quite as bad again.”

RENMARK

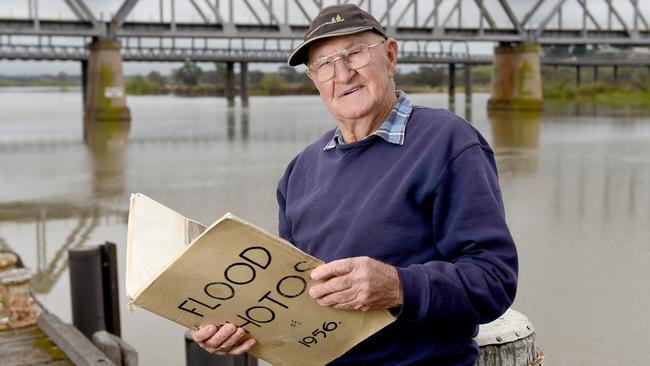

COLIN Roy was just 18 when the river came to swallow up his home town of Renmark.

Locals knew there was water on the way but Mr Roy says the seriousness of the threat took many by surprise.

Renmark was ultimately saved but the town was surrounded, homes inundated, businesses crippled.

“It wasn’t considered dangerous at the beginning,” the 78-year-old recalls.

“They thought it might flood some of Renmark but it wasn’t considered to be a super flood until it came on later on in July and just kept on rising.

“Every day it would peak and then rise again, so the job on the banks was continually to increase the height, and every day there’d be water lapping over.”

“It was all hands to the deck.”

“We still had First World War guys who’d been over in the floods in France and Second World War people, most of them were in their prime actually, so it was interesting timing.

“The Second World War guys had only been out of the army 10 or 11 years and here they were combining a force and we just joined in.”

There was what they called a “Crash Gang” too, which was made of young fellas that slept all in the one building and if there was any alarms went off they were the first on the scene.

Writing in The Advertiser on August 22, 1956, journalist Max Fatchen called the gangs “the shock troops of the flood battle”.

“Break! Someone shouts and the crash gang of 22 young Renmark men roars away to yet another threatened levee,” he wrote.

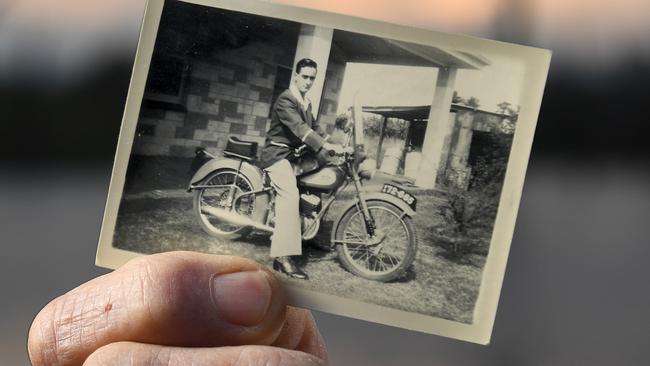

Mr Roy had an important job of his own - motorbike messenger.

“I had a little Bantam BSA, little two-stroke, and my job at one stage was to ride along the banks to deliver messages from one person, you know from the boss, the leader of our area to the banks. It was pretty slippery, because a lot of the time it was raining and very cold.”

Later, he was tasked with trying to protect some of Renmark’s biggest buildings.

“It was of concern that the floors of the buildings would expand and push the walls over so our job was to go and break every, god knows, fifth or eighth board on the floors, especially the old high school, then the hospital.

“The floorboards still swelled up and became like a trampoline afterwards; you could walk on them and bounce up and down.

“Whether we did any good I don’t know. I mean, most of us had never been through a flood of that type.”

Mr Roy says the water sat around for months, long after the peak had passed.

“They had to get these big water harvesters in, most of them run by tractors, and they pumped the water from one side of the flood bank back into the river again.

“It would never have dried up. It would have taken years.”

He says whether SA could see another flood as bad is anyone’s guess.

“Maybe we’ve got a better handle on it now with, you know, satellites and all that sort of thing, we can perhaps understand it more. But I don’t want to see another one.”

MANNUM

WHEN the Murray flooded the main street of Mannum, John Banks just went with the flow.

Mr Banks, then 23, was an avid amateur rower but when swelling floodwaters threatened the local rowing shed, members were forced to move the club to higher ground.

“We used to then carry the boats out over the sandbags and put them in the water, in front of the Pretoria Hotel and row them down the main street as part of our training,” he says.

“We had to do that because the river was flowing so fast and in among it was debris of all sorts.

“It could be logs, it could be timber from shacks; at one stage there was a whole roof of a shack floating down; it was too dangerous to go out on the water.”

A now-iconic photo preserves the moment.

In 2006, for the 50th anniversary of the flood, Mr Banks, 83, and the foursome snapped rowing alongside him, were invited back to Mannum to re-enact the moment.

“We rowed past the crowd down and back again just to say we could.

“It was a big day,”

Like Renmark, Mannum copped the full force of the flood and many businesses paid a heavy price.

“All of them on the river side of the main street closed, they just got flooded out,” Mr Banks says.

“The Bank of Adelaide, which it was then, they had to close because people couldn’t get in and do business.

“The flour mill kept operating most of the time, the bakery, Bormann’s Bakery, which was right alongside of the Bank of Adelaide, they actually got flooded out on August 24.

“It breached the sandbags and flooded his bakery so he then had to take all of his equipment and go up Adelaide Road and bake up there.”

Water, water everywhere but there was still time for a drink.

“The hotel managed to scrounge up enough of their gear, took it upstairs and they did a roaring trade up on the balcony,” Mrs Banks recalls.

“That’s where they carried on their business, on the balcony of the Pretoria Hotel.”

There was another small blessing - the fishing was good.

“There seemed to be fish everywhere and we used to catch them in nets - and of course in those days we could - and every Sunday we’d put them in a pound, clean them of a Sunday morning and go up Adelaide Rd and sell them to the people coming up from Adelaide in the afternoon,” he says.

Mr Banks recalls one particularly eventful fishing expedition.

“We were down one night running our nets and we could hear this noise, and it just sounded like a storm coming, wind, and we sort of got out of the boat, went up on the hill to my brother’s place and I said ‘I bet you I know what that is, the bank’s gone’ and sure enough, it had,” he recalls.

“So we rang one of the dairy farmers across the river, Rathjens, and told them about it and the next thing there were lights going everywhere, people getting their cows off of the swamp.”

Mr Bank says says the flood left locals with a “big, big clean-up job”.

“The Murray’s black mud was everywhere - in the shops, in the main street, wherever you went there was this black mud,” he says. “It was certainly a Wellington boots job!”

MU RRAY BRIDGE

ACCORDING to Ken Wells, people in Murray Bridge plot history at two points on the spectrum; “Before ’56 and after ’56”.

“Oh, that happened before ’56’, ‘Oh, no it didn’t, it happened after ’56,” Mr Wells, 81, explains.

“Fifty-six is like a dateline, you know.”

Mr Wells was 21, living and working on the family market garden and orchard, south of town.

Murray Bridge, perched on a hill, was never in danger of inundation.

But there was still much to be protected – machinery relocated, hay sheds shifted.

The scariest part about it was nobody could tell us when the water would get to its peak.

“You just had to keep going and when the low-lying areas were being threatened, or when one levee went, say, north of Murray Bridge, well you went and did what you could to help,” Mr Wells recalls.

“It was three or four months of solid flood work.

“We had a terrific lot of volunteers from Adelaide, interstate, the Mid North; they would come here in busloads. We even had, at one stage, the wharfies come up by bus at weekends.”

He says authorities, too, did what they could to support the local effort.

When water flooded the Wells’ farm pump house, the pump and motor were floated in a dinghy across a swamp, propped up on 44-gallon drums and plugged into a neighbour’s pipeline.

“They brought a wire down to the starter motor, connected it, and away we went,” Mr Wells says.

“Now, you’d never do that in a hundred years today - occ health and safety wouldn’t allow it.

“But they (flood authorities) shut their eyes and did what they could to help the people out.”

Mr Wells says the floods seriously compromised farming in the area but growers soldiered on.

“We were growing citrus and stone fruit, the same with like Mypolonga - a lot of their orchards were flooded out. Some of them had to pick their fruit by rowing boat,” he says.

But it was the dairy industry that was hardest hit.

“From, say, Mannum down to Wellington to the lakes, there were about 14,000 dairy cows. Well, they had to be re-agisted to other areas of the state and interstate.

“The factory got flooded, so other factories around the Adelaide Hills and interstate had to be taking more milk where the cows were up in the Adelaide Hills, down in the south east, interstate and some of the dairymen had to go with their cows to milk them.”

For many in the district, it was a long road back to normal.

“By the time the river come down it would have probably been 18 months to two years before we got back into real production along the river.

He says “catastrophe” is not too strong a word to describe the flood’s impact.

“I think it would have been, because it was such a long, long drawn out affair and it went from the top of the state at Renmark, right down through the Lakes and further afield.”

“It just spread and spread and spread.

“And the force of the water going out the mouth - it was recorded that the brown mud that was coming down the river was about 40km out to sea”.

“I mightn’t see it in my time but I do believe that we’ll have another one.”

Greg Barila was born and raised up the road from the Riverland, in Mildura.

This article was first published on Advertiser.com.au in September, 2016

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

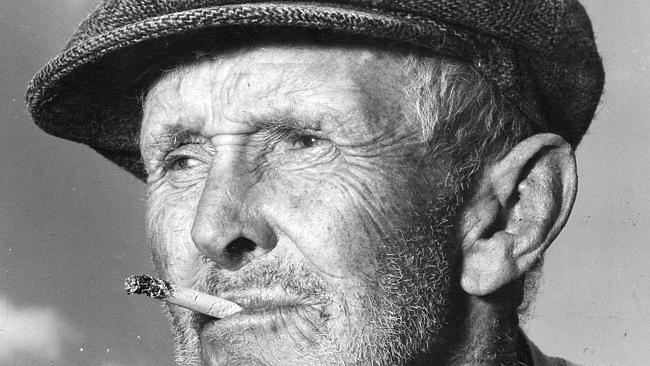

Mugshots: Faces of South Australia’s criminal past

These are the haunting faces of South Australia’s rich criminal history. From murder and theft to the “crime” of fortune-telling, delve into these fascinating records of our villainous past.

Discover a dream family holiday

FROM exciting new water parks and resort-style swimming pools to picnics under the trees, Discovery Parks at Tanunda and Lake Bonney will make your summer holiday one to remember.