IN the late 1920s, thousands of furious waterfront workers stormed the docks at Port Adelaide, armed with baling hooks, pipes and iron bars, and attacked non-union labourers. Twice in one day. The police were ready for them the second time.

But the striking workers, raging over changes to their award and government legislation that opened dock work to non-union members, wouldn’t give up so easily.

A couple of months later, they did it again, this time prompted by their women.

The time was 1928 and the scene was Australia’s heavily unionised waterfronts. High unemployment was rife. Jobs were hard to find — and keep. The Communists were biding their time, and they used this to push their agenda.

That September came a new waterfront workers award by Justice George Beeby, one that was basically everything the Waterside Workers Federation — one of the nation’s first and most militant unions — didn’t want.

Not only did it remove overtime restrictions to speed up ship turnaround times, it toughened smoke-o rules, lessening break time. This infuriated the men, whose shifts could range from 16 to 48 hours.

It also strengthened the bull system by introducing two daily pick-ups.

The bull system allowed for a foreman to pick his bulls, or favourite workers, each morning from queuing hopefuls. The system was open to corruption — some foremen demanded wage kickbacks.

Unions wanted the pick-ups abolished. But the award simply standardised them to two a day. While some cities already had two daily pick-ups, Adelaide did not.

It meant hopeful workers had to wait around for hours if they missed their chance on the first one, but still could miss out later that day.

The day after the award came into force, September 11, shipping at Port Adelaide came to a standstill as waterfront workers refused to show up.

Heavily laden ships sat in the harbour, with food, wool, grain, produce, building materials and more sitting unused in holds.

Quickly, the strike began to affect other industries — The Advertiser at the time reported seamen and carters were put on notice, or had no work.

The strike became a national response. The first instance of free labour was used in Tasmania to unload food. Seamen were beginning to be paid off and sent from their idle ships, while other ships left Australian ports with their cargo still on-board.

So the ship owners responded — by calling for volunteer workers, for which the Beeby award allowed. At first, the ploy worked.

On September 16, the WWF voted, by a majority to end the national strike. Newspapers reported that the “red element” — the Communists — protested.

And so did the workers. Chaos erupted across the country, as workers defied the union’s vote. As the strike continued, the Government acted. It introduced, during an all-night sitting, what became known as the Dog Collar Act — forcing anyone who wanted to work on the docks to first obtain a licence.

Aimed at opening the docks to non-union workers, for the unionists it was a (probably red) flag waved at a bull.

At the same time, volunteers were enrolling to help unload the ships, many in the hope of getting paid work later.

The stage was set for violence as unionists sought to protect their jobs from the “scabs”.

Uneasy calm

The first sign of trouble brewing was when the SA police force began to strengthen its force in Port Adelaide. Sudden doubling of police in cars, on horses and foot patrols tends to suggest someone is worried.

In Parliament, questions were asked — succinct answers given that, yes, there more police in Port Adelaide.

Strikes continued across the nation. By September 20 all police leave was cancelled. Country stations were closed or reduced to one man. Barricades were erected at the port to protect the docks, and the volunteer workers on the ships.

The press also reported special constables — more volunteers — were appointed to bolster police numbers.

Then, a sensational twist — the reds emerged. At the weekend of September 22, in Adelaide the WWF unionists held a secret ballot to decide if they would return to work.

Two men stormed into the hall while the vote was taking place and grabbed the ballot box, throwing it to the ground.

Later identified as the “red element” by newspapers, they cast the votes around, and threw them out the door.

Quite conveniently for the Communists, a gale was blowing at the port that day. The votes were gone in seconds.

By now, 350 volunteers were unloading ships at Port Adelaide, with few disturbances and arrests. The strike broke in Melbourne, Brisbane and Newcastle, but not in Adelaide.

The anger was growing — and now the Government’s Dog Collar Act came into force.

It broke the uneasy calm.

The first riot

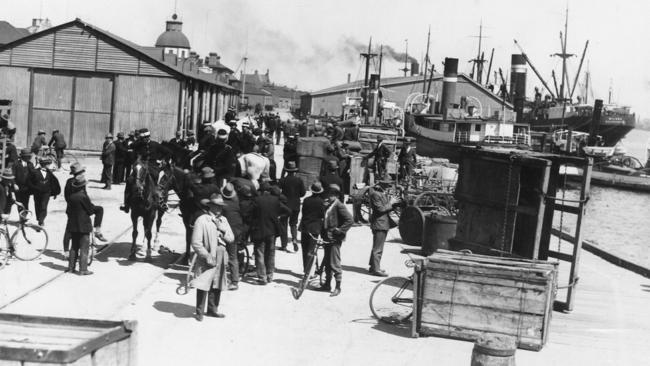

On September 27, the dog collars themselves — the licences — came into effect. Furious, four thousand dock workers marched towards the now-demolished Robinson’s Bridge (think McLaren Parade), which crossed over the No. 1 Dock at Port Adelaide.

Their numbers swelled — the unemployed, idle members of other unions joined the march. The huge crowd, as many as 5000, stretched all the way back to Commercial Rd.

They said they had been advised to present themselves for work — but upon hearing they had to apply for a licence, they swarmed across Robinson’s Bridge and on to McLaren Wharf, aiming to force the volunteers to leave.

“We had to do something,” one of the union members told The Advertiser. “We could not allow these men take our jobs like this.”

In the thick of 5000 angry men, many volunteers couldn’t escape the chaos. Some were offered the chance to leave safely, but most were not — as the violence grew, some jumped overboard and hid in the water, under the docks.

One climbed the funnel of a ship, others sought refuge up in the cargo nets.

Volunteers were assaulted; some workers used pipes, iron bars, lengths of wood, and even baling hooks or pelted volunteers with stones.

Volunteers were thrown to the ground, kicked repeatedly. Several men had the vicious baling hooks driven into both buttocks and both thighs.

Quickly, the police moved into action, and eventually dispersed the rioting workers, but not without trouble — the officers were vastly outnumbered.

Many volunteers were taken to hospital with broken bones, damaged kidneys and wounds from hooks.

But the riot wasn’t over.

The second riot

That afternoon, 2000 men marched six miles to Outer Harbor to try to scare off the volunteers there.

Just why they left isn’t clear — some of the workers wanted to “clear up Outer Harbor too”, while others claimed that, in clear sign of the crazy-brave actions only present in 1928, the volunteers at Outer Harbor reportedly sent a telegram to the unionists.

It said, The Register reported, “Come and get us if you can. We’ll fix you up.”

Clearly, they hadn’t heard about the baling hooks.

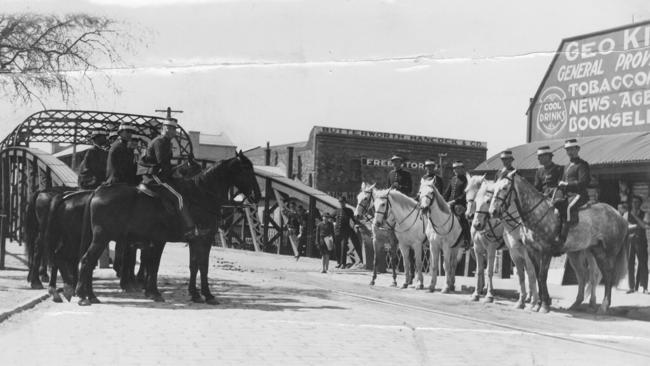

The taunt worked — the march was on, but this time the police were ready.

The 2000-strong mob neared the southern end of the wharves at Outer Harbor, they were met by decorated World War I hero, Police Commissioner, Brigadier General R.L. Leane.

He walked out to meet them, pleading that they leave.

The mob ignored him and ran on towards the ships, but General Leane had his plan in place.

First, mounted officers moved towards the stone-throwing mob. Horses, struck by thrown rocks, reared through the clouds of dust as their riders deflected the mob towards an area behind Outer Harbor railway station.

It was a scene “probably without parallel in the history of the state”, The Register wrote.

Some rioters climbed on to the platform and hurled rocks at the troopers — suddenly, from behind, they were attacked by a cordon of baton-wielding plainclothes police, who “speedily routed them with the attention from batons”.

One police officer’s hat saved him from serious injury when a burly dock worker hit him in the head with a stone — the cap’s peak took the force of the blow, tearing it off the hat.

Running from the batons, the mob headed towards the wharves between two buildings.

But here was the second line of defence — foot police. Meanwhile, the mounted officers blocked their escape at the rear.

The ship’s crews had been ordered to haul up the gangways — and watched as the 2000 rioters were quickly quelled.

Some of the union leaders tried to rile the men up, but they didn’t bite. For a while, they waited around hoping to get delegates in contact with the union, but it wasn’t working. Slowly, the men drifted away.

The press at time reported few arrests, and those arrests that happened were largely for assaults on police officers — people who had attacked police officers often said afterwards they hadn’t realised they were an officer.

Many of the arrests were for smaller, single events — rocks thrown at a car or train. The rioters appear to have been largely allowed to leave.

In the days that followed, there was serious rioting in Melbourne; a Gallipoli veteran was shot when a police officer decided not to use blanks, while the Citizens Defence Brigade was formalised in Adelaide.

It grew to more than 2000 special constables. Rifles were issued, as well as army service kits. They left their ordinary lives and went to man the barricades along the wharves, living in tents near where the Diver Derrick Bridge is today.

Smaller, occasional riots occurred in Port Adelaide, but nothing like the previous one. By October 8, nearly all unionists were back at work across the country.

The march of the women

The rioting was not completely over, nor was the use of volunteer labour, which continued. At one brief riot, the woman were heard to say they’d do it right, if their men kept getting it wrong.

And on Friday, January 18, 1929, a couple of days after that was reported, a march went very wrong.

The march of the women began after an afternoon meeting of the wives of unemployed men.

During the meeting, a man outside stood on the back of a truck and began to regale the men standing around, saying only a general strike across the nation would see better pay and working conditions for workers.

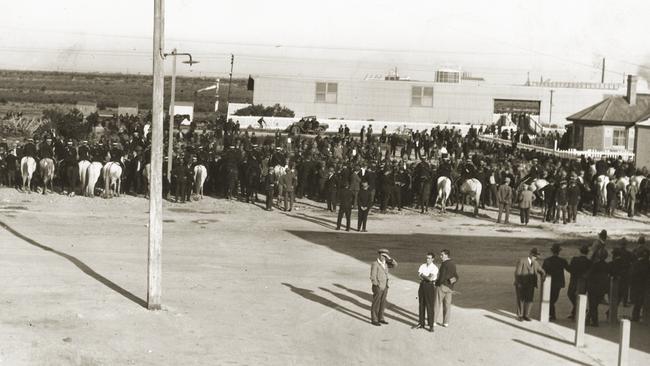

About 800 women, many with children and infants, then began a peaceful march along Commercial Rd, but were joined by about 900 men.

As they marched, one woman grabbed and waved a red flag — a Communist symbol, but the press reported that she was joking.

She was urged to put it down by the march leaders, but another man grabbed another one.

It wasn’t long before the march split — near Divett St, marchers rushed the steamer Van Spilbergen, where volunteer workers were loading wheat. Many of them climbed the rigging to escape.

Police on horses moved in quickly, and the riot was on — batons used on “freely” on women, children and men as wood, stones and bottles were thrown at the officers.

As the rioters fought to get on to the steamer, the police fought back.

A child was hit by a police baton, and lost two teeth — a mother thrust her child into the arms of a nearby reporter and presumably rushed back into the riot.

In the rush, many people tried to hide in nearby shops. Others dropped their shopping parcels in the street and ran away.

One newspaper reported this eyebrow-raising fact: “An inspector was severely handled and scratched by hysterical women.”

Peace slowly returned to the streets of Port Adelaide, and by mid-October, the waterfront strike was largely over. While sporadic, spontaneous strikes continued, volunteer labour was slowly abandoned.

More reading

LOOK BACK: Nine of the biggest blazes in Adelaide’s CBD

GALLERY: And more historic photos of life in SA in the 1930s

PHOTOS: Everyday life in SA and Adelaide in the 1920s

References

Information taken from Trove

Special thanks to the SA Police Historical Society: this report from former chief superintendent of the SA Police Force Wallace B. Budd and two reports from Detective Senior Sergeant Barry Blundell — which you can access here and here.

Stanley Bruce — Australian Internationalist, by David Lee, Bloomsbury

Waterfront: Graft, corruption and violence — Australia’s crime frontier from 1788 till now, by Duncan McNab, Hachette Australia