World War I SA pilot Thomas Baker was killed in a dogfight — 100 years ago

FIGHTING on after most Australian troops took a well-earned break from the battles of World War I, SA pilot Thomas Baker was killed in a dogfight — 100 years ago today — tragically close to the November 11 Armistice that ended the Great War.

HIS name is Thomas Baker but everyone calls him Richmond, just like his dad. He sits at the kitchen table of his Smithfield farmhouse, concentration etched into his young face, carefully piecing together a model plane.

The Wright brothers have taken to the air for the first time near Kitty Hawk, South Carolina, just a few years earlier but already the world has fallen in love with flight and all that it promises.

The globe is shrinking rapidly as the aircraft promises to one day link the continents of the earth, and little Richmond — like many kids of the day — is fascinated. He wants to fly.

But before the plane can prove itself in peace it’s forced to prove itself in battle as the world is plunged into history’s most terrible war. As men battle in the mud to capture a few yards of precious ground, the air above becomes a battlefield of its own as both sides realise the devastating possibilities of waging war from the skies.

It is in one of these planes — a Sopwith Snipe — that the boy who dreamed of flying died, shot down by enemy aircraft near the town of Ath, Belgium, on November 4, 1918. He is just 21 years old.

Captain Thomas Charles Richmond Baker was one of the very last Australians killed in battle during that terrible war but not before he demonstrated a level of skill and bravery rarely seen.

He was, in the words of fellow ace pilot Lieutenant Leonard Taplin, “one of the most brilliant boys”.

Thomas Charles Richmond Baker was born on May 2, 1897, to farmer and schoolmaster Richmond Baker and his wife Annie. Now a busy residential suburb, at the end of the 19th century Smithfield was very much rural South Australia, 30km north of the growing capital of Adelaide.

Baker attended St Peters College from 1911, embracing the sporting side of high school. He rowed for the school and played tennis in the summer and football in the winter, and after finishing in 1914 he was employed as a clerk at the Adelaide branch of the Bank of NSW.

On July 15, 1915, Baker — with his mother’s consent — signed up to serve his country.

In November he shipped out for the Middle East as a reinforcement gunner for the 6th Field Artillery Brigade. Soon after his battery was moved to France, arriving in time for the first battle of the Somme.

Despite his young age Baker was a born warrior, showing considerable courage on the battlefield.

On December, 15, 1916 — deep in the European winter — the South Australian won his first Military Medal. Near the commune of Gueudecourt, Baker was part of an observation team sent forward to secure an area for bombardment.

While doing so he repeatedly repaired broken telephone lines — vital lines of communication for the Allied forces — all the while being shot at by enemy troops.

Not long after he added a Bar to his Military Medal when, ignoring the obvious danger to his own life, he extinguished a fire in a gun pit packed with around 300 highly explosive artillery shells.

Despite his skill as a soldier, Baker never let go of that dream he’d had since the days he used to glue together models on his Smithfield farm.

In August of 1917 he remarked that he was “almost green with envy” on seeing Allied aviators in action. He knew his fate lay in the skies.

Securing a spot as a mechanic in September, 1917, Baker was soon singled out for flying duties and, after training with the No. 5 Training Squadron, he made his first solo flight in March, 1918.

On June 15 he graduated as a Sopwith Camel pilot and joined the No. 4 Fighter Squadron.

With a grand total of 57 hours and 40 minutes of flying time under his belt, Baker was off to battle.

The young Australian took the bravery he showed on land into the skies, and quickly earned a reputation as a fearless and skilled pilot.

In just four months — June 23 to November 4, 1918 — Baker shot down no less than 12 enemy planes from the cockpit of his Sopwith Camel and Sopwith Snipe.

On July 31 he took out a Fokker D. VII, and one week later destroyed an Albatross D.V. On August 24, he shot down an enemy balloon, followed by DFW C. On October 1, he brought down another Albatross, followed by two more Fokkers on the 2nd and 26th. On October 28, 1918, Baker is credited with shooting down no fewer than three German planes during two patrols into Belgium. The next day he brought down yet another German Fokker, and another the day after that.

It was an incredible run in an incredibly short time, but it was about to come to a tragic end. A prolific letter writer, Baker’s last note home was a Christmas card to his mum. Written in October, it is filled with optimism and hope for the future.

“Greetings from the 4th Squadron AFC France” the front reads, above an etching of a biplane in action. “This card was designed by a couple of air mechanics as a Xmas greeting to the ‘mob’,” Baker writes.

“I hope that it will be a jolly happy one. I am sure mine will be after the great victories we have had. Much love to you all, Rich xxxxxx.”

Baker would never see another Christmas. On November 4, just a week before the end of the war and 10 years to the day since his own father died, Baker led a formation of Sopwith Snipes as part of an escort for a bombing raid on a German aerodrome near the Belgian city of Ath.

Returning from the successful mission, the Australians came across a larger number of enemy aircraft and a fierce dogfight ensued. The Snipes took out four German planes but when they regrouped they realised five of their own, including Baker, were missing.

The South Australian was initially reported missing in action after other pilots reported seeing his plane crash land behind enemy lines, but air and land searched failed to turn up any trace of him or his plane. In February of 1919 a court of inquiry determined he was killed in action.

It later emerged that Baker’s plane, and that of one of his colleagues, was shot down by Commander Rittmeister Karl Bolle, a famous German pilot credited with no less than 36 aerial victories.

It took an ace to take down our own ace.

Retired Army Colonel and creator of the online Virtual War Memorial, Steve Larkins, says Baker’s story is an important one for South Australians.

“He was just 21 when he died but he’d already earned two medals and a Flying Cross (awarded posthumously),” Mr Larkins says. “It really beggars belief.

“In terms of our history, South Australia produced a number of great aviators, but Baker was certainly up there with the best.”

Perhaps the final word should go to Baker’s old St Peter’s schoolmate Stanford Howard who served with his friend.

“From the outset he showed abilities as a pilot far above the average,” he wrote for the school.

“His sterling qualities were soon recognised. After very little experience he was leading patrols.

“He was the friend of all inexperienced pilots because they knew Baker would not leave them long in any predicament … his machine could be seen darting here and there, always to the help of those in difficulties.”

He was, Howard said, “the most gallant airman that left these his native shores.”

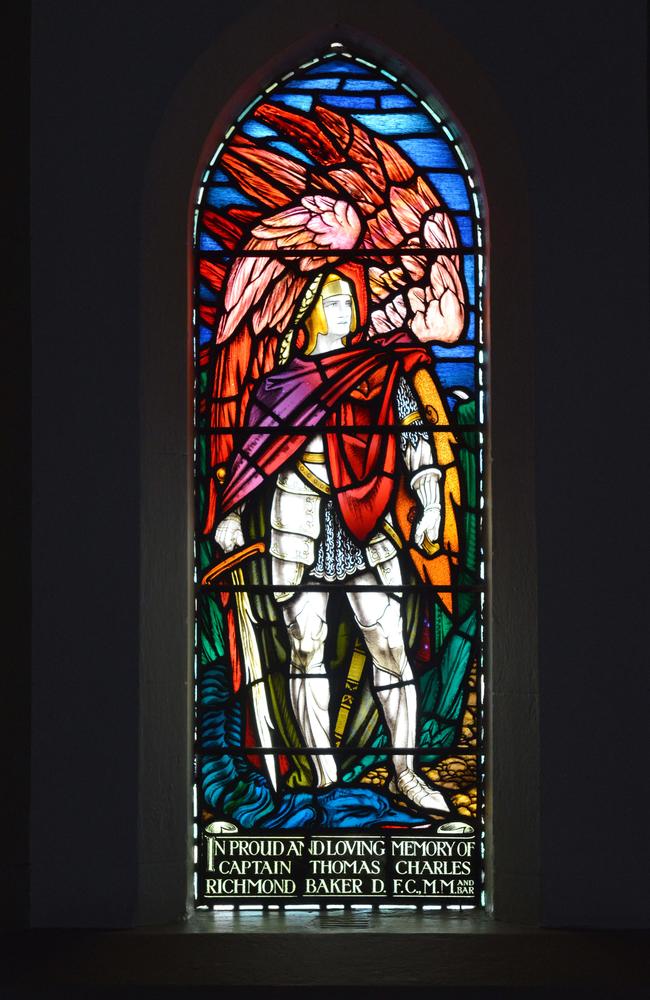

Thomas Charles Richmond Baker is now remembered by two stunning stained glass windows in St John’s Anglican church on Halifax St, a permanent reminder of a life that ended too soon.