Why we need more male teachers in SA schools

AS THOUSANDS of students head back to the classroom this week, some will be walking through the gates of schools that have no male teachers.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AS THOUSANDS of students head back to the classroom this week, some will be walking through the gates of schools that have no male teachers.

Numbers of men in the profession have continued to decline over the past five years, leading to calls for a public education campaign to promote the profession to men who see teaching as “women’s work” or are fearful of accusations of child abuse.

The added complexity of more single-parent households and higher divorce rates also has highlighted the importance of a male influence in a child’s life.

Australian Education Union state president Howard Spreadbury says there is a need for a closer gender balance.

“It wouldn’t hurt to have some sort of campaign to represent the benefits of having both genders well-represented in the profession,” he says.

At independent school Trinity College, about two in every five primary years teachers are men, compared with fewer than one in five on average across the public system.

Principal Nick Hately backs the idea of a public campaign, saying it is time for men to realise that being part of a “very caring industry” could be “a strong part of male identity”.

The proportion of male teachers in the public system has fallen from 35 per cent at the turn of the century to well below 30 per cent. State Education Department figures show:

MORE than 50 schools — about one in 10 — had no male teachers in a snapshot taken in June last year. Most were small country schools;

MEN comprise just 17.4 per cent of the primary school workforce, but a fairly healthy 43.1 per cent in secondary schools;

OVER the past five years, the number of women has risen by 909, or 7.8 per cent, to 12,555, while male numbers are down 125, or 2.6 per cent, to 4693;

MEN are slightly better represented in city than country schools overall;

THE proportion of male university enrolments in teaching courses rose from 25.7 per cent in 2010 to 28.1 per cent in 2014, but the proportion of male graduates did not improve over that period.

SA Primary Principals Association president Pam Kent says the gender imbalance will remain until the status of the profession is restored, and the culture of fear around accusations of child abuse is addressed.

“These days, teachers are fair game for criticism from parents who tend to be overprotective. That would never have happened 20 years ago,” she says. “It’s seen by men and women as a tough job without much status.

“The big block at the moment is the fear and vulnerability of young men with child-safety (issues).”

Education commentator and former Education Department executive Graeden Horsell says there appears to be no “targeted strategy” in making teaching in public schools more attractive to men.

“Teaching in the community is seen as a low-status job, the wages they earn are not what they could earn elsewhere,” he says.

“There’s significant pressure to make sure there are as many female principals as there are male principals — it seems (gender rebalance) is more important at that level then at a teaching level.”

He says the flow-on effect is that there is also a lack of male teachers taking on roles as coaches of school sporting teams.

In 2000 Mr Horsell, as president of the SA Association of State School Organisations, wrote a submission to a federal standing committee investigating the education of boys warning that departments have “failed miserably to redress the feminisation of the education workforce”.

In the paper he wrote that boys have higher school dropout rates and poorer academic outcomes compared with girls, suffer more learning disabilities and behavioural problems compared with girls and that there should be the development of a gender education strategy.

Education Minister Susan Close says the low proportion of male teachers is disappointing given family circumstances mean some children have no male role model at home.

The idea that teaching was primarily a female profession “seems to have quite a grip even on the younger generation”, she said.

In his acclaimed book Raising Boys, author and psychologist Steve Biddulph said the 6-14 age range was a period when boys “hunger for male encouragement” and role models.

“So it’s vital we get more men into primary school teaching, not just any men, they have to be the right kind of men,” he writes.

“Something has to be done about boys’ motivation,” he says. “It’s clear that schools can and must change if they are to become good places for boys.”

Heading bush to make a difference

ANYONE who thinks teaching is a cushy job should consider Josh Jenner’s chosen career path.

Straight out of university, the 25-year-old’s first classroom will be in an indigenous school near the Northern Territory border, where he will have responsibility for up to 25 students spanning six year levels.

And unlike many who don’t last long teaching in remote communities, he’s determined to be in it for the long haul.

Originally from Watervale in the Clare Valley, where he attended Clare High School, Josh moved to Adelaide in 2010 to study for degrees in Aboriginal studies and middle and secondary education at UniSA.

He is of Aboriginal background but said he had no exposure to Aboriginal history at school, so is determined that indigenous children under his wing won’t miss out. What he did have was a teacher who guided him along the right path.

“I had a media studies teacher in Year 12 who was a good influence on me and got me to look at Aboriginal education and Aboriginal studies (uni courses),” he said.

“I enjoyed the Aboriginal studies subjects because we didn’t learn anything about that at school — nothing whatsoever.”

In his uni classes for becoming a teacher, he was one of just a few males.

“Probably 10 per cent of the classes I was in were males so it’s definitely a big gender gap,” he said.

“I think it’s because of the stigma over the years that only females are teachers and males do hands-on things like the trades.”

At Murputja Anangu School, Josh will be teaching students from Year 7 to 12 in the one class — 14 to start with, but likely to grow to as many as 25 — with the help of two or three Anangu support workers.

“It was always my goal to go out there. My plan is to stay up there for at least five years, and if I like it I’ll probably stay there indefinitely,” Josh said.

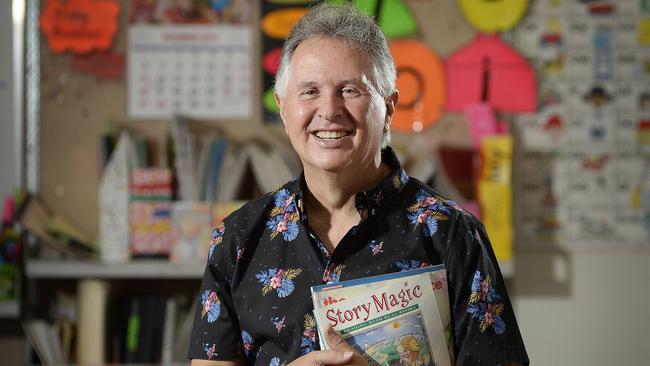

Tough times worth the effort

STEVE Campbell can understand why many young men shy away from teaching, but he would never dissuade anyone from the profession he has loved for the best part of four decades.

He knows it’s difficult getting permanent jobs.

Teachers start off doing relief work, then have potentially years of contracts before a secure job becomes available.

“If you are at the stage when you’re getting married and buying a house, that can be difficult,” he said.

“But I’d still encourage anyone to go into (primary) teaching. The kids are at an age when you can mould them a fair bit.”

Mr Campbell, 59, began his career at Redwood Park Primary in 1978 and spent most of the 1980s in country schools at Coonalpyn, Mypolonga and Murray Bridge, followed by Adelaide and the Hills.

Next month, he officially retires from Woodcroft Primary, where he has taught since 2007.

Mr Campbell said much had changed over the course of his career.

Technology has made “chalk and talk” teaching “a thing of the past”, and the job was now “a lot more interesting, a lot more visual, a lot more instant”.

However children’s constant exposure to technology has changed their behaviour and made teaching more demanding.

“They don’t tend to concentrate as much as they did in the past,” he said.

“You can talk to them for about five minutes before you start to lose half of them. That’s not a bad thing. You have to be organised and get them to do things”

Then there’s the introduction of the Australian Curriculum, much more data collection to be done and, of course, NAPLAN testing.

“Society holds us a lot more accountable than it did before,” he said.

And these days he wouldn’t dare think of giving a student a cuddle or putting one on his lap without parental permission.

Trent strikes chord as male role model

IT’S not unusual for mums to ask for their children to be placed in Trent Stafford’s reception classes.

“In this day and age there’s a lot of single-parent families or split-parent families where a lot of kids don’t have a male role model,” he says.

“I’ve had single mums request their sons or daughters be in my class because of that very fact, just to have a positive male role model in their life.”

Trent, 41, has taught at Trinity College for 21 years.

, currently at the Trinity North campus at Evanston South

“I was one of four males in the state in my year who graduated from junior primary teaching at university,” he said. “When I first started at Trinity I was one of the only males but that’s growing.” I’ve been able to see the growth of (male teacher numbers) through the college.

About 45 per cent of Trinity teachers are men, principal Nick Hately says. In the primary school, it’s roughly 40 per cent.

Trent, who is also a qualified music teacher and makes use of his guitar skills in the classroom, says some young men still see teaching in an outdated, stereotypical way as a “female job”.

He said they needed to know it was a rewarding career that allowed for creativity as well as satisfying outcomes — such as guiding reception students with no literacy skills at the start of the year, to writing their own stories by the end.

Trent said gender was not a determinant of teaching style, but there were differences between male and female teachers.

“As a male, I think we bring a different mindset in dealing with problems,” he said.

Trent said he would not support any discriminatory incentives for young men to become teachers, because that would risk “attracting the wrong people” without the necessary passion for the job.

But he backed the idea of a public education campaign to promote the profession to men.