University of Adelaide research to predict Parkinson’s disease risk after head injury

Hard knocks to the head cause lasting damage such as Parkinson’s disease in some people and scientists want to understand why. Now a $2 million SA study is developing a new forecasting tool to predict a patient’s long-term prognosis.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Mark Mickan’s second chance after surgery to slow Parkinson’s

- How to get the most out of your Advertiser subscription

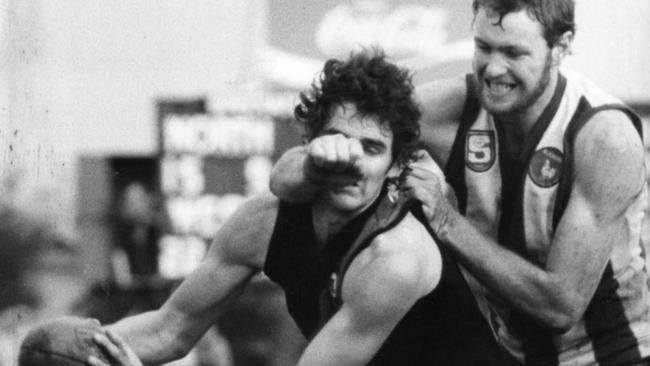

In a football career spanning more than 200 matches, Mark Mickan was not immune from blows to the head.

“I got hit in the head several times during my time in the game, but I can’t remember any one instance in particular that would be the deal-breaker,” the 59-year-old, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2016, said.

“There were times when you’d get hit in the head and you’d feel a bit dazed for a few minutes, then someone would come out and say ‘How are you going?’ and I’d say ‘I’m all right’ and you’d keep going …

“Then the clubs just went with what they knew at the time and treated you accordingly.”

University of Adelaide researcher Associate Professor Lyndsey Collins-Praino is now on a $2m quest to investigate any links between head knocks and Parkinson’s.

She has received Federal Government funding (Medical Research Future Fund) to develop a new forecasting tool to predict a patient’s long-term prognosis after head trauma.

“Right now, if you have a head injury, because we don’t know what your ultimate outcome might be, it can feel really scary,” Dr Collins-Praino said. “That’s why research like this is so important, because it helps us to identify risk and take that critical first step to being able to do something about it.”

Following a promising pilot study funded by the NeuroSurgical Research Foundation, the new three-year study will soon recruit patients with traumatic brain injury.

Imaging techniques will be used to see how the brain and body is functioning. Blood tests will check for various biomarkers of brain inflammation, over time.

“This is significant, as we can then compare this to the same markers in both healthy individuals and those who have an established diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease,” Dr Collins-Praino said.

“This will allow us to generate a unique brain injury neural signature. Then, using machine learning, we can generate a risk prediction algorithm,”Dr Collins-Praino said.

If all goes to plan, Dr Collins-Praino said, neurologists will be able to intervene earlier and offer much more targeted clinical management of people deemed most at risk of degenerative disease.

“It gets toward personalised medicine, where we know if person A has a head injury and they meet these criteria that say they are at increased risk for Parkinson’s, then there are things we can do,” she said.

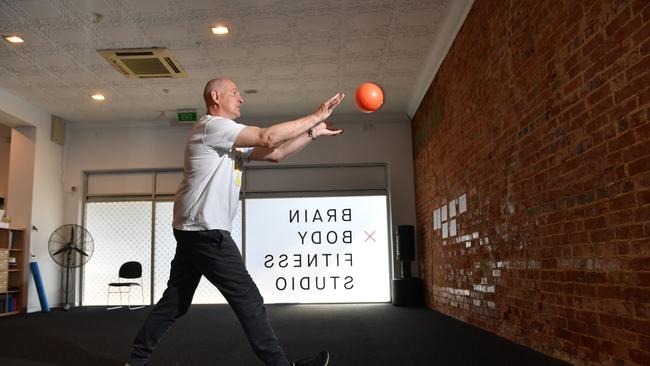

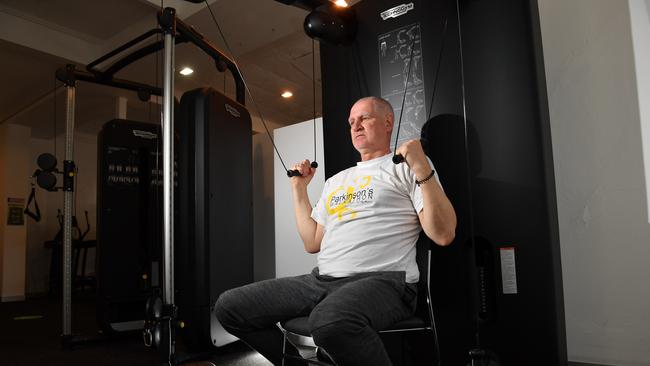

“That might include identifying them as a participant for clinical trials, helping to get them involved with different rehab strategies like cognitive training and other programs that we know can be really beneficial in delaying onset of neurodegenerative conditions.

“It opens up the idea of tailoring a program based on their risk profile.”

Mickan’s Parkinson’s diagnosis came 14 years after the end of his AFL and SANFL career.

His country upbringing (it carries a higher risk of chemical spray exposure), football career and a family history of Parkinson’s put him in a higher risk category.

“Footy gave me the best years of my life, and you sign up knowing there’s a possibility you’ll get hit in the head I suppose,” he said.