UN IPCC releases most comprehensive climate change report since 2014, SA scientists say situation has gone from bad to worse

The most comprehensive climate change report to date shows Earth will warm beyond agreed limits. An SA scientist details what the bad news means for us.

South Australia is facing more extreme heat, drought and catastrophic bushfires with drastic consequences for health, agriculture and biodiversity, the most comprehensive climate change report in seven years reveals.

The report finds the planet is very likely to warm by 1.5C in the early 2030s.

Hundreds of the world’s top scientists analysed the evidence and projections to update policymakers on the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) came out in Geneva on Monday.

Interpreting the report for South Australians, Flinders University’s global ecology Professor Corey Bradshaw said the situation had gone from bad to worse.

“It’s no longer just about our kids or grandkids, it’s about us, if you’re alive today, you’re already experiencing climate change,” he said.

“What frightens me more is that the IPCC employs conservative language in these certainty statements, so the trends are in reality much worse than stated.”

Professor Bradshaw said it was clear South Australians should expect:

More frequent and longer-duration droughts that will reduce our agricultural production;

More intense bushfires, making the 2019-20 fire season appear modest in comparison;

More frequent and intense heatwaves that will kill both vulnerable and healthy people alike;

More intense winter storms that will lead to localised flooding, property damage, and deaths;

More extinctions of plants and animals across the state than are caused now by feral predators and forest clearing;

More flooding of built-up areas along our coasts as sea levels rise combined with more intense storm activity.

Scientists have observed changes in the Earth’s climate in every region and across the whole climate system, but warming has been greater on land than at sea.

The report by the IPCC’s Working Group 1, which will set the terms for the international climate conference in Glasgow this November, also shows global warming will likely break through the internationally-agreed two degree target limit by 2060 even with big cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

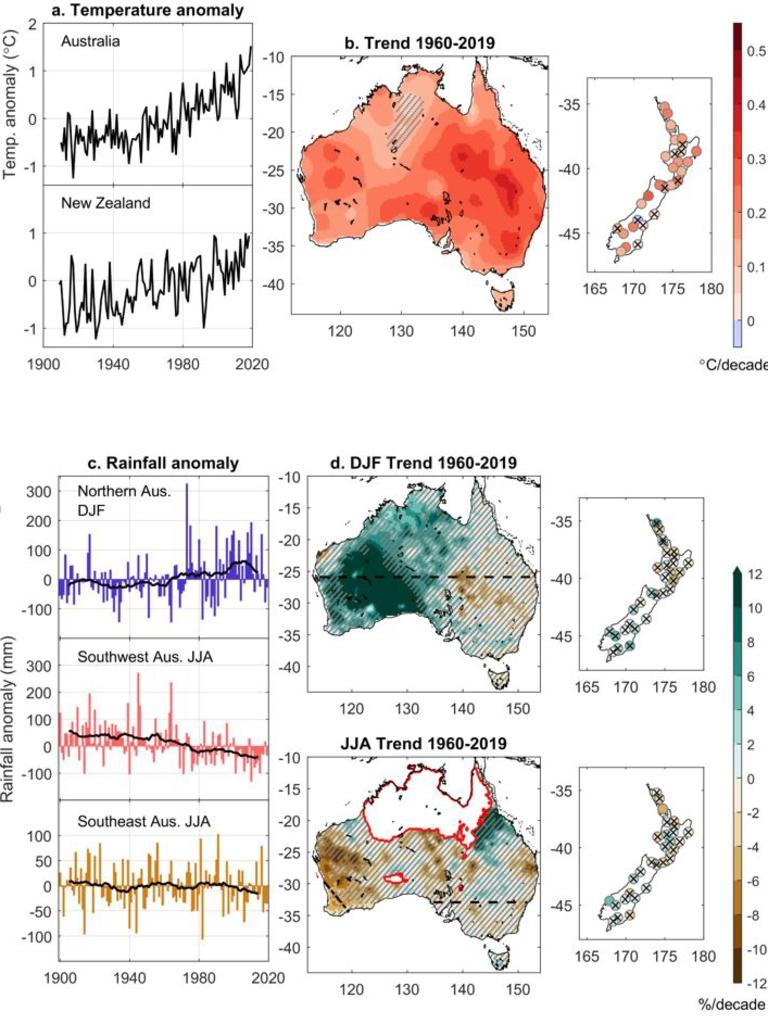

Australia is racing ahead of global averages for both land warming and sea level rise.

While global temperatures have risen by 1.09C, land areas in Australia have warmed by around 1.4°C.

Seas are rising an average of 3.7mm a year (more than doubling the rate observed between 1971 and 2006), but the rate in Australia was “higher than the global average in recent decades,” the IPCC stated.

IPCC projections show temperatures will continue to rise, regardless of what agreements are struck at Glasgow, although the rate of that rise will depend on how much greenhouse gas continues to be pumped into the atmosphere.

Even under an intermediate emissions scenario, which allows for very small global increases in greenhouse gases over the next two decades before massive cuts, the planet will be 2 degrees hotter around the middle of the century and 2.7 degrees hotter towards the end.

Under that same scenario, sea levels will be around 50cm higher by 2100 and as much as 1.3m higher by 2150.

One of the Australian lead authors, Dr Pep Canadell from CSIRO’s Climate Science Centre said to think of it like the planet hurtling down a slippery slope at great speed, with no end in sight, but we can put on the brakes.

“There’s no bottom end to how much damage we can create,” he said.

“But we’re still in control over where we want to take the future of this planet … it really shows the incredible (need) for humanity to take action.”

Australian lead author of Chapter 3 of the report (Human influence on the climate system), Associate Professor Shayne McGregor of Monash University said every little bit of warming averted would make a difference.

“It’s not too late,” he said.

“Every action is beneficial, every half degree or 0.1 of one degree makes a difference so it’s time for large scale, sustained reduction in greenhouse gases.”

Dr Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick from the Climate Research Centre at UNSW said there was “still a chance” for the world to pursue the intermediate emissions scenario, but warned Australia would continue to be at the upper end of temperature projections.

“We’ll always be a bit hotter than the global average,” she said.

“We don’t have that much wiggle room in terms of our current annual emissions.

“They can increase it a little bit over the next couple of decades, but then we really need to be drastically reducing our emissions. We need to sort it out now.”

The report’s summary for policymakers includes the bold claim that under any emissions scenario, the Arctic will experience one ice-free summer before 2050, but it makes no statements about the future health of that other canary in the climate coalmine, the Great Barrier Reef.

Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said the report’s predictions of increasingly intense heatwaves was “really bad news” for the reef.

“Kiss it goodbye as we currently know it,” she said.

The IPCC’s Working Group 2 report, due in February, is expected to look more closely at climate impacts on individual ecosystems such as the Great Barrier Reef.

Director of the ANU Climate Change Institute Professor Mark Howden said much of the data from the report was not new, but the “strengthened language” and “increasing confidence” around claims was significant.

That strengthened language is apparent from the very beginning of the report, which stated: “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred.”

Prof Howden said he had been involved in drafting IPCC reports since 1991 and seen them move from the margins to a position of centrality in policy terms. The reports were coming under more scrutiny than ever before, with the summary for policy makers “approved word by word and line by line,” by governments and scientists, he said.