Two adopted boys reshaping child protection in SA

The fate of twin boys adopted in London is helping SA take the first step in long-overdue child protection reform that will result in fewer kids separated from their families and being moved into foster and state care.

The most momentous event in Peter Sandeman’s life is one that he can never recall.

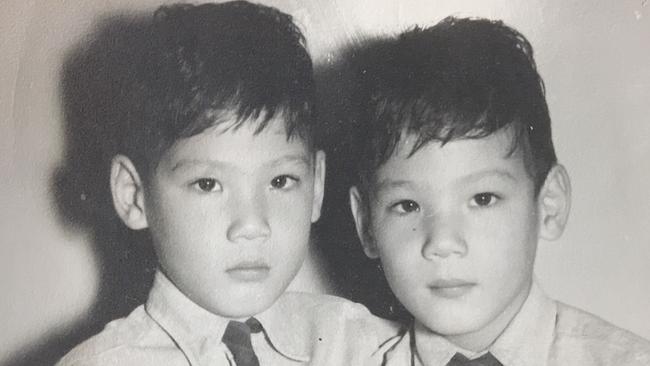

Shortly after his birth, Peter’s mother was forced to abandon him and his twin brother, John, at an orphanage in London in 1955.

The ripple effects of that pivotal moment 64 years ago however have reverberated deep and wide across Peter’s life as a child, and now CEO of AnglicareSA.

“I was never able to reunite with my mum,” he says.

Peter discovered when he was 15 that he was adopted, but it wasn’t until his 40s that he attempted to find his birth mother.

“By the time I went looking, my mother had died, so I knew very little of her.”

Closed adoption — when the records of biological parents are kept sealed — was common and actually peaked in the decades after post-World War II when Peter and John were placed into Barnado’s Orphanage in Tunbridge Wells after their birth in March 1955.

Today, closed adoption is no longer supported due to the detrimental psychological effects on the adopted children and their parents.

From what Peter and John have been able to discern through records and family letters, their mother was Toshiko Ohtani.

She was a Japanese woman in post-British Commonwealth occupied Japan in 1954 who fell pregnant to a US Army engineer while she was betrothed to a British Army major.

The American soldier left her.

She coped with the aftermath of their affair alone. Her British fiance, Major Peter Simon, ignored the infidelity but refused to be a father to the twin boys.

Toshiko, riddled with cultural shame, was forced to choose between a life as a single mother in Japan or one with her future husband in London.

“To this day I have a conflicted understanding of my identity, because my race and upbringing are totally unrelated to each other,” Peter says.

He has never visited Japan. John has. “I haven’t been able to follow up on my relatives in Japan,” he says. “There will come a time when it is important I do that.”

Toshiko died aged 56 in Tokyo. She never became a mother again.

Peter’s experience is the driving force behind a child protection pilot program set to break new ground in SA.

AnglicareSA’s Safe Kids Families Together pilot program starts on Monday.

Its ambitious aim is to keep 92 at-risk families from Adelaide’s northern suburbs together — ultimately preventing 276 children from entering out-of-home care (OOHC), like the orphanage where Peter and John spent the first several months of their lives.

“If children can remain safely with their birth family, then that is the best place for them,” says Peter.

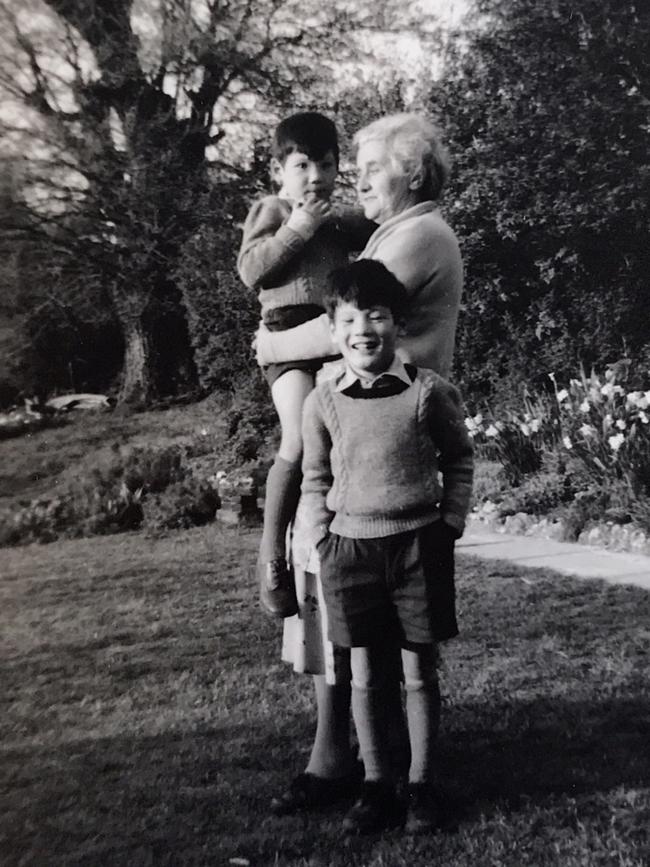

The brothers were adopted by Colin James Sandeman and Ethel Mary Sandeman in 1956.

They were lucky not to be have been separated at the time of their adoption. Many orphan siblings were adopted individually — losing complete touch with their family ties for many years, if not forever.

Colin Sandeman — a British Army captain who had fought against the Japanese in World War II — chose to welcome Peter and John into his home over twin girls of similar age who were of African-American descent.

Colin had spent five years away from Ethel Mary and their daughter Sylvia while deployed in India and Myanmar. The couple, who had married late, were then unable to have more children and so decided to foster and adopt.

While her husband was serving in British India, Ethel Mary had opened her home to evacuee children during World War II and began informal fostering.

It was a humanitarian act that received honorary appreciation from The Queen, who sent a personal message to Ethel Mary, who sacrificed much of her own comfort to share her home with those in greatest need.

The family’s strong sense of social justice stemming from deep Christian devotion left a lasting imprint on the twins.

“We had an idyllic upbringing,” says Peter.

“It was a loving, conservative upbringing and it was our second chance in life.

“We were extremely fortunate compared to the life we could have had in that orphanage and the discrimination we could have faced as half Japanese orphans after the war in the UK.”

In 1961, Colin and Ethel Mary packed their children — Peter, John, their older brothers Anthony and David, and older sister Sylvia, to migrate from Sussex to Australia. Colin had been recruited as an architect to Adelaide.

The boys were six years old when they settled in Hillcrest — avoiding the White Australia policy of the 1960s through some creative passport photography.

Despite the obvious physical differences to his adopted family, Peter says he was oblivious to his Japanese heritage.

“We were never told that we were adopted — it wasn’t the done thing at the time,” he says.

“I grew up thinking I was a blue-eyed, blonde child of the Empire and had no awareness of being half Asian at all. And then high school hit.”

It’s here that the racial taunts began and Peter was forced to wonder where he belonged.

“The other kids knew, but I was clueless,” he says. “They nicknamed me Tokyo Joe.”

The teenager eventually confronted his parents over his birth origins. “It came to a head when I was 15,” says Peter.

He found documentary proof of not only his and John’s adoption but also that of Anthony and David.

He says the knowledge of his adoption sent shockwaves through him. He rebelled at school, while his brother John preferred to pour his focus into books.

“It was a life changing time.”

Today, Peter is an Anglican deacon who has spent over 40 years in social work, social justice and welfare services at Anglicare in SA and NSW, Mission Australia and federal and state governments.

John, who is based in Sydney, is editor-in-chief of the Bible Society of Australia’s monthly publication, Eternity newspaper, and is also the society’s publishing and digital manager.

This follows 27 years as a Fairfax Media journalist and art director, including at the Sydney Morning Herald and Financial Review.

“I think Peter took the adoption much harder than me,” John says.

“Both of us have been marked by adoption. It’s true that adopted people worry about their identity and sense of self — that is true of me.”

John suspects his anxious and nervous tendencies are a by-product of closed adoption.

But he also recognises their fate could have been one that many children from foster and state care live through at a significant cost.

Studies have repeatedly shown children in state care are more likely to experience homelessness, unemployment and mental health issues.

“We were extremely lucky,” John says.

“I also think that Peter and I are comparatively unscathed because we had each other — we were not separated — that is incredibly powerful.

“We have always known someone who is connected genetically, which is very important for adopted people.”

Right now in SA, there are almost 4000 children aged up to 17 separated from their families and some from their siblings too, according to the latest figures from the Child Protection Department.

And it’s not a figure that’s abating either.

In the past 10 years, the number of SA children in OOHC has almost doubled. While states like New South Wales and Victoria have reduced the rate of kids entering OOHC in the last two years, SA maintains the highest rate of all the mainland states.

Peter says it’s just not good enough. “We need to reverse this trend,” he says.

“We need to strengthen and empower families to enable them to keep their children safe at home — now and over the long term.

“There is much to be done to turn around a system in crisis but supporting vulnerable families is a vital first step.

“We are absolutely committed to driving change and having a real impact on families and children at risk of removal.”

While he acknowledges there are some children for whom removal is the only option, he also wants greater emphasis on more permanent, stable OOHC with open adoption as an option and reunification as an end goal to better the life outcomes of kids separated from their families.

“Children should be able to have all the benefits of an ongoing ‘forever family’ while retaining their identity and sense of self and ideally rebuild a relationship with their birth family when it is safe and possible to do so.

“If my mum would have been able to keep me and my brother, it would have been much better for us all. It was not possible for her.

“But we should try and make it possible for so many mothers forced into the sacrifice of giving up children or having their children removed and for fathers to be supported to be great dads.”

SUPPORTING CHILDREN, PARENTS IS A ‘NO-BRAINER’

Investing in preventive child protection measures that keep families and siblings together is a “no-brainer” with immeasurable social and economic benefits, child advocates say.

“It’s not just about the immediate cost saving but also the long term social and economic welfare costs — because kids in care tend to have poorer life outcomes,” AnglicareSA community services general manger Nancy Penna said.

Ms Penna said research had identified up to 46 per cent of male youth in state care were involved in the juvenile justice system and 65 per cent of youth in state care did not finish Year 12. From tomorrow, she will help manage a team of specially trained social workers in a new trial aimed at diverting children from out-of-home care (OOHC) by better supporting their families.

The Safe Kids Families Together pilot program responds to Royal Commissioner Margaret Nyland’s findings in 2016 that SA’s investment in intensive family support services was well below the national average.

Meanwhile, spending on OOHC — despite lifelong negative impacts on kids — continues to rise.

The Productivity Commission’s latest Report on Government Services states that under current policy settings, the SA expenditure on OOHC and child protection services over the next five years is estimated to increase by $382.1 million per annum, with $851.3 million to be spent in 2022/23.

Jacqui Read, CEO of advocacy group CREATE Foundation, said preventive investment in keeping families and siblings together when it was safe to do so was a “no-brainer”. “We need to increase preventive programs to decrease the number of children in OOHC and increase the quality of OOHC to ensure kids have positive outcomes,” she said.

CREATE’s latest report shows SA, while improving, had the highest rate of sibling separation in care of the mainland states. In 2015, 53 per cent of children in care in SA were separated from their siblings, compared to 43 per cent in 2017.

Uniting Communities CEO Simon Schrapel estimates that at the current rate of increase, the number of children in OOHC will reach 4500 by the next state election in 2022. “Jurisdictions around the world have shown when families who need it receive the support and intervention required to keep children living safely at home and enable them to return home safely after being in care, that the rates of OOHC and the associated public expenditure can be significantly reduced,” Mr Schrapel said.

He said in NSW and Victoria the number of children in OOHC had reduced after major investment in early intervention, prevention and reunification. “Unless we have the courage to make these investments (in preventive measures), I think we will continue to be overwhelmed by the number of children ending up and remaining in care,” he said.

“While there will always be some children for which there are no options, we must stop relying on out-of-home care now as almost a default system for our failure to adequately support families.”

The State Government is currently consolidating services and staff across departments to create a new intensive support system to stem the flow of children entering the child protection system.

CHILDREN IN STATE CARE

63% of homeless young people have been in state care

46% of male youth in state care involved in juvenile justice system

65% of youth in state care do not finish Year 12

30% of youth in state care are unemployed as young adults

SOURCE: Various Australian and overseas research