Truth about the Repat Hospital’s World War II air-raid shelters

HISTORY MONTH: Buried under the ground at the Repat is a long-lost relic of our wartime past — air-raid shelters, complete with a stainless-steel, ready-to-go operating theatre. So say the stories, anyway.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

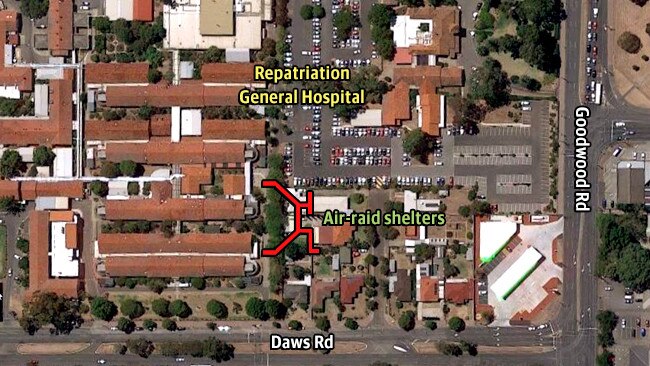

BURIED below the ground near the Repat Hospital lies a remnant of Adelaide’s wartime past — World War II air-raid shelters.

They’re long gone, of course. Filled in, supporting timber and iron removed sometime after the war, with the ground now sold off. Houses and carparks cover what was once a bolthole for the Repat’s staff and patients in World War II.

But the stories remain, handed down by Repat staff, taking on a life of their own — witnesses steadfastly maintain they have seen stainless steel operating theatres and hospital beds that experts say “can’t have been there”.

The shelters were built by the military in 1942, and the entrances probably sealed off and filled in after the war, probably during the early 1950s. But their exact locations were never recorded

A 1947 article in The Mail on the day the hospital was passed from the military to the Repatriation Commission, talks about a “huge air-raid shelter built to accommodate about 300 patients”.

“Barred and deserted, the air-raid shelter remains today,” the article says. “It will shortly be dismantled to make way for the foundations of a new chest hospital.”

It appears to be the sole reference to the bunkers in Trove, the national newspaper archive.

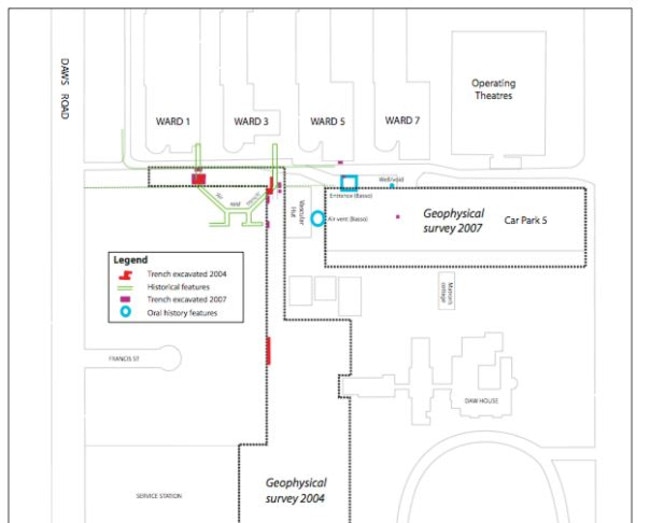

A three-year Flinders Uni archaeological survey that ended in 2007 found the entrance to one of the shelters, but little else.

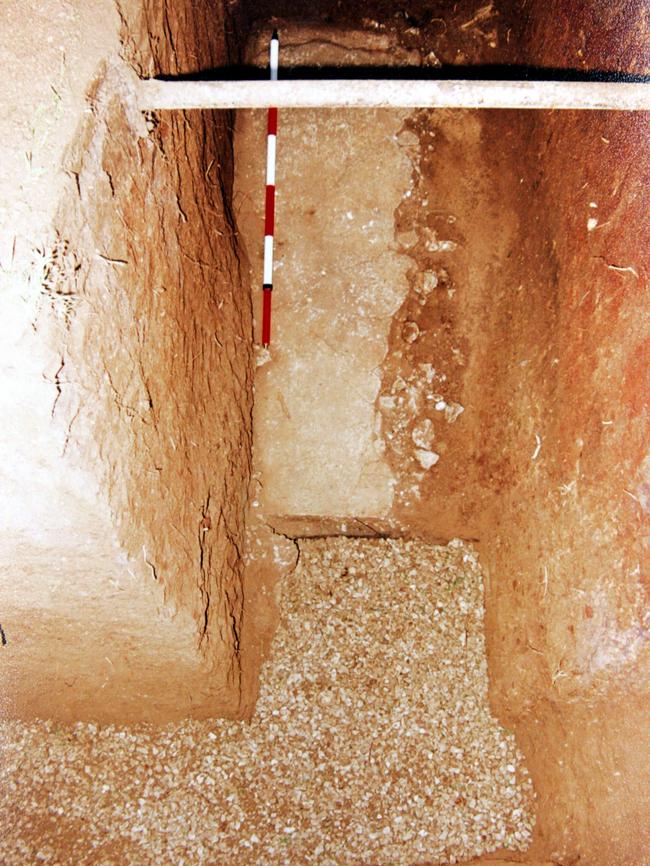

Buried under 1.5m of hard-packed dirt was a cement, a gravel walkway, and remains of timber — probably one of the entrances.

Found in 2004, and re-excavated in 2007 for more study, it’s the only tantalising remnant of what used to be there.

Much of the land where the shelters were thought to be is now private property — or housing, preventing further exploration.

THE STORIES

Even before the war ended, the shelters were become a nuisance for Repat supervisors. Staff and patients would sneak down there for a smoke or privacy with girlfriends — or their not-girlfriends.

Exactly when they were filled in is unknown, but the Flinders study found an earthmoving contractor called Kerry Simpson who delivered truckloads of dirt to the area of the entrances from 1960, and later a bulldozer. He had played in the shelters as a schoolboy.

Aerial photos from 1950 show the entrances, but in 1958 photos they aren’t visible.

However, and here’s where the contradictory evidence begins. Long-time Repat staff member Steve Basso told the Flinders Uni survey that he was shown an open entrance when he began working there in 1970.

“There were no lights, when they opened the door there was no electricity, no anything else … it was just all black,” he said.

“I remember there was a trace of water in front of me on the floor. He [the old orderly who

showed Steve the shelter] brought out his big standard torch [and] shone it down the end and I can remember that the torchlight didn’t reach the end of it. It seemed to just go on and on.”

Mr Basso didn’t go any further into the shelter, fearing more, deeper water.

Fellow staff members Ken Mayes and Darren Renshaw said that in 1985, a contractor digging a trench for a water pipe uncovered stairs leading into a room.

“It was filled with dusty old beds and furniture,” Mr Mayes said.

“It was bricked up the next day and the trench refilled. Unfortunately, we do not know exactly where that was.”

A former orderly, Dennis Stopps, said that in the late 1970s, construction broke through a brick wall to reveal an entrance to the shelter. Inside were steel bunk beds, bed pans and instruments.

Other former staff members had even more elaborate stories, and over time, those stories have grown, to tales of a fully equipped surgical theatre buried under the ground — an air-raid shelter large enough to take 300 people, with a dining area and beds.

Mr Basso told the survey of the “stories that were told when I first started here”.

“That … there were four theatres down there, the corridors were wide enough to hold a hospital bed and have another hospital bed pass them at a push.

“That there were ancillary rooms as well, that they were all fully equipped with instruments for surgery, with trolleys, supposedly [they] had kerosene lanterns, I think, rather than any electricity.

“That they could hold 300 and something patients between three units at any one time. … We were told very clearly by some of the older senior nurses when I first started here, too, that if needs be they could use them because everything was set up, the instruments, the trolleys, the trays, were all there.”

Some of those stories were intended to frighten, or impress new staff.

“You wouldn’t believe the sort of stories we used to get told — [that] there are probably some bodies here from the war, [that] this is where they put the people that died that shouldn’t in surgery, all these sort of things that they tell young people when they first start in a hospital,” said Mr Basso.

“And you never really knew what was true and what wasn’t, and you didn’t want to really take the chance, just in case there were some bodies!”

But those later, more elaborate, stories are very unlikely to be true.

THE REALITY

Dr Heather Burke, associate professor in archeology who led the Flinders Uni survey, says she found no evidence to prove the existence of operating theatres or hospital beds.

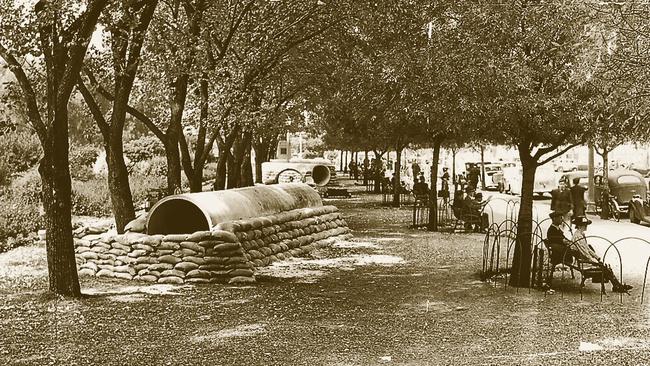

The air-raid shelters were a “simply made” connected series of covered tunnels, constructed of iron and timber — nothing like what the later stories made them out to be.

“We saw what they ordered when they made those bunkers (for World War II),” she said. “It just had to do its job.

“After we spoke to Repat staff, the stories of the shelters after the war didn’t match with the physical evidence.

“They said they saw beds, but far as we can tell, none of those stories can be true — and even some of those people told us they were eyewitnesses.

“Some were second, third-hand, some of these stories are handed down. But there is just no historical evidence, archaeological evidence, It can’t be true.”

But Dr Burke says that makes the stories about the Repat shelters “even more fascinating”.

“People tell us these stories — when everything shows they can’t be true.”

She said that as soon as the air-raid shelters disappeared, the stories “started to get increasingly elaborate”.

Some of the older people who spoke to the uni’s investigation played in the shelters in the 1940s as children, and talked about “big long tunnels” with wooden ceilings and walls reinforced with timber of corrugated iron — a far simpler set-up than later tales.

“A stainless-steel surgical complex underground could never be true, ever — no one has ever invested that kind of money in the Repat,” Dr Burke said.

“It was much simpler and less exciting than the later stories of surgical equipment and hospital bunks and an underground operating theatre.

“Something to do with that being lost, it started that chain of storytelling — I can’t explain that, but there’s interesting human psychology going on there.

“These bunkers, they aren’t there (now) — but they’re an important way for people to identify themselves, so important that they took on a life of its own.

“The stories shouldn’t be dismissed — it how they’re being part of that community.”

THE DIG

The Flinders Uni project excavated several sites around the Repat — one in 2004, and more than a dozen in 2007 and in between, spoke to about 25 current and former staff and community members about their memories of the shelters, some of which were second-hand stories.

It found the walls of the shelter had probably been formed by the natural hard clay, reinforced by a timber framework and galvanised iron to create walls.

Iron formed a roof, with a wooden ceiling, and dirt covered the top.

The paddock under which the shelters ran was sold off and subdivided for private housing between 1954 and 1959, so it’s likely the structures were removed before that, and the trenches filled in.

Some stories indicated one entrance was located in Dawes Paddock — Kerry Simpson recalled as boy finding his way into the shelters, exploring them, and coming out the other end to find himself in the hospital grounds, suggesting they were extensive.

Little is known of the shelters’ ultimate fate. There’s nothing documenting their removal or demolition, but the Flinders study found it unlikely they lasted much longer than the end of the war, because they attracted “a congregation of undesirables” engaging in “drinking and unseemly conduct with ... women”, according to the Adelaide Military Hospital War Diary.

It’s probable the bunkers were filled in sometime between 1949 and 1958.

THE OUTCOME

The entrances were on hospital grounds, but the bulk of the bunkers were under the field to the back of the Repat, which was sold off from 1954 for private housing.

Some of the staff recall the army blocking off the entrances with concrete, while others remember the tops being knocked off and the empty tunnels bulldozed.

Later, voids and holes were found during work on carpark five, where once a square brick construction emerged from the earth — a possible air vent, which was called “The Thing”.

Mr Basso told the Flinders interviews that “things started falling down into two holes” during construction.

“They found two holes and so they kept pouring rubble and crap in it to fill them up because they thought they were wells and they couldn’t have those in the carparks.

“I remember talking to one of the contractors who was working at the time telling me how many tons of stuff he had to pour down the hole to fill the damn thing in before they could actually bitumenise over the top.”

Asphalt had been poured over the likely original spot where “The Thing” emerged from the earth — and a trench dug nearby in the hope of discovering more holes found nothing.