Truro murders: Former detective reveals why he broke the law to ensure justice in notorious SA serial killings investigation

FORMER senior detective Ken Thorsen, who led the Truro serial murders investigation in the 1970s, breaks his silence to reveal why he had to break the law to ensure justice.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Truro murders — the untold story. Read Nigel Hunt’s special investigation

- How Niki found out about the murdered mum she never knew

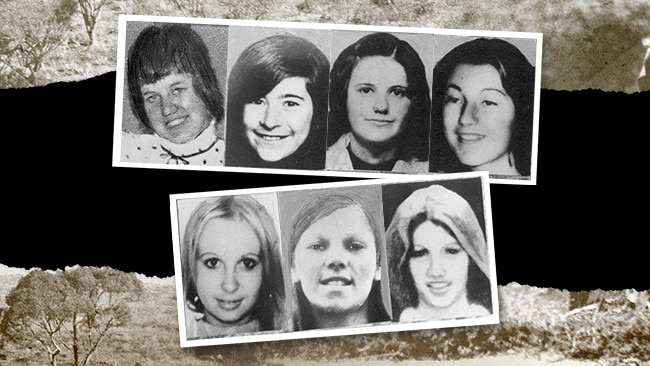

- Gallery: The Truro murders

SENIOR police were aware they were deliberately breaching the law when they took suspected serial killer James William Miller to Truro to locate the last three victims’ bodies, it has been revealed.

Breaking his silence on the controversial move on the eve of the 40th anniversary of the abduction of the first Truro victim, retired detective Ken Thorsen — the senior officer who made the crucial decision — said he believed doing so was “the only way to recover the missing girls’’.

While the illegal actions could have resulted in the entire prosecution case against Miller being thrown out of court, they were instead the catalyst for legislative change that legalised such police activity in serious cases.

Police have never before spoken about their unorthodox actions in the case, which were the subject of an unsuccessful defence challenge prior to Miller’s trial and his subsequent failed attempt to overturn his six murder convictions on appeal to the Full Court of the Supreme Court.

Although the three appeal judges all found police had acted unlawfully, they said the action was justified because of the gravity of the crime being investigated and the fact Miller had volunteered to assist.

“I want to reiterate it was my decision and my decision alone,’’ Mr Thorsen said.

“I knew what we were planning to do wasn’t legal under the legislation as it stood at that time, but to this day I firmly believe that if we had not acted as we did that night Miller may have changed his mind.

“If he did, those girls would still be missing today. It was the only chance we had to find their bodies and return them to their parents.

“And I had a gut feeling that because of the gravity of this crime, it would be a very brave judge who would exclude the evidence that flowed from our actions.’’

Under Section 78 and 80 of the then Police Offences Act, once a person was charged with murder they had to either be released on bail or put before a court “forthwith’’.

But in Miller’s case, after being formally charged with one murder — that of the sixth victim Connie Iordiannes — he was released into the custody of Major Crime detectives and voluntarily went to Truro and later other locations at Port Gawler and Wingfield to locate the three missing victims’ remains.

He was subsequently charged another six counts of murder — the killings of Veronica Knight, Tania Kenny, Julie Mykyta, Sylvia Pittmann, Vicki Howell and Deborah Lamb.

When Miller faced trial in the Supreme Court in 1980, his barrister Kevin Duggan, QC, argued that evidence gained after Miller was taken from the City Watch House should be excluded — which would almost certainly have seen three of the seven murder charges withdrawn.

However, trial judge Roderick Matheson used his discretion to admit the evidence, later stating “the probative value of this evidence clearly outweighed its prejudicial value’’ even though “removal of the accused from the custody of the watch house sergeant was illegal.’’

Miller, who died in custody in 2008, subsequently appealed his convictions to the Full Court — with one ground focusing on the evidence and confessions obtained after he was charged with the first murder, taken from the watch house to locate the three bodies and further questioned at police headquarters.

In the Full Court judgment, Miller’s appeal was dismissed by majority, despite the three Justices finding police had acted unlawfully the night he was charged.

In the judgment, then chief justice Len King said he had “no doubt that the action of the detectives in taking the appellant to the places mentioned were unlawful’’.

“If the suspect has not been arrested and he is willing to accompany the police officers, no problem arises,’’ he stated.

“The law is stringent in its requirements as to the management of arrested persons and those requirements must be complied with strictly, however inconvenient and difficult that may be in the course of carrying out an investigation.’’

Justices Andrew Wells and George Walters, who dismissed Miller’s appeal, also said his “removal immediately after being charged was unlawful’’ and he was “unlawfully in custody’’ while being taken to search for the three bodies and while being further interviewed afterwards at police headquarters.

“The balance of the competing public interests ... lead firmly to the conclusion, in our judgment, that the police officer’s infringements of S 78 and 80 are dwarfed by the enormity of the crimes which they were then in the course of investigating,’’ they stated.

Mr Thorsen, who was Superintendent in charge of the Major Crime Squad during the Truro investigation, said he was “acutely aware’’ of the ramifications of his decision because a murder case had been dismissed only months earlier because two uniformed officers had contravened the same section of the Police Offences Act.

In that incident the officers attended a domestic murder at Croydon and encountered the offender on the footpath and he had made partial admissions. At trial all evidence gained from his confession was excluded because it was obtained unlawfully under the Act and the charge was dismissed.

Mr Thorsen said following that case he had a meeting with then crown prosecutor Kevin Duggan, QC, shortly before he went to the private bar, to discuss the limitations of the Act and it was resolved to “wait for the right case to test it in court’’.

A senior silk acutely familiar with the Miller trial said in his opinion the move could have resulted in all seven of the murder charges against Miller being dismissed — not just the charges in connection with the last three skeletons located by Miller.

“If the charges over the last three bodies and the confessions post charging had been successfully challenged and ruled inadmissable because of what took place, then the remaining charges would have been tainted,’’ the silk said.

“My feeling is they were very, very lucky. Despite the gravity of the offending in the case the evidence could quite correctly have been excluded by the trial judge.’’

Former Major Crime detective Peter Foster, who was one of Miller’s arresting officers, said he recalls the discussions over removing Miller from the watch house after he had been charged.

“The law wasn’t clear. We were not sure of the ramifications and there were discussions about what we should do seeing he had been charged,’’ he said.

“It bothered us because we just didn’t know. There was no doubt we were getting into a grey area. We had progressed whereby we had an offender, it was one of the more serious crimes that had occurred in the state and you wanted to do the right thing.

“It was a real problem, you didn’t want to get caught out late in the proceedings.’’

- This is an edited version of a story first published in December 2016.