Tiger Mum murder trial: Why Wei Li was found guilty of manslaughter, not murder

IF law student Wei “Daniel” Li has told the truth, he killed his demanding mother in a fight to the death at their Burnside house. Colin James reports.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Stroke of luck that led to Wei Li’s conviction

- Accused murderer hired male prostitute days after mum’s death

- Wei Li went to China to ‘forget about’ killing mum

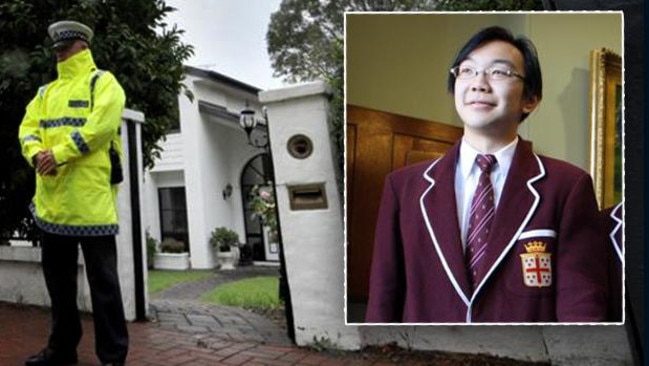

IF Chinese law student Wei “Daniel” Li has told the truth, he killed his demanding mother in a fight to the death at their Burnside house.

His evidence has been enough to convince a jury not to convict him of murder but instead find him guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter.

There was no dispute Li, 23, had killed his mother. It was whether he had done it deliberately or with premeditation.

Last week, he stood in the dock of the Supreme Court for almost two days describing how he had no clear memory of what happened on the day Mrs Tien died or what he did for four days before he flew to China.

Li, a former University of Adelaide law student, told the jury of six men and six women that he could only remember his mother charging at him, yelling abuse for not practising the piano in their Burnside home.

He gave sworn testimony that his mother — portrayed by his lawyers during the trial as an archetypal Tiger Mum — was hysterical as she started hitting him with an iron rod.

Telling the jury he acted in self-defence, the former high-achieving student at Prince Alfred College and accomplished musician said the pair violently struggled until his mother stopped moving with his hands around her throat.

Under intense cross-examination from prosecutor Jim Pearce, SC, Li insisted he had not “killed” Mrs Tien but instead had “caused her death” defending himself.

Mr Pearce accused Li of lying, being evasive and fabricating his version of events pefrom before his mother died to when he flew out of Melbourne for China four days later — accusations he vehemently denied.

In her summing up, Justice Trish Kelly explained to the jury that even if a person lied during their evidence, this was not enough to convict them of murder.

Neither could a person be found guilty of murder if they killed someone by using lethal force to defend themselves.

It had to be proven, beyond reasonable doubt, that Li deliberately intended to kill his mother.

The jury, she said, had three verdicts to consider — guilty of murder, not guilty of murder or guilty of manslaughter.

They could not begin to deliberate about manslaughter, she told them, until they had decided if he was guilty of murder. If they did, such a decision had to be unanimous.

If they found him not guilty of murder, only then they could consider whether he was guilty of manslaughter.

Justice Kelly told the jury that along with self-defence, provocation was one ground for finding someone not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter.

The jury had to consider, she said, if Li was provoked by his mother, who had constantly demanded he achieve the highest possible academic results, speak multiple languages, play three instruments to perfection and work in the family’s furniture shop in the Adelaide CBD.

According to Li, the fight was the latest in a series of violent confrontations which had been happening since he moved from China to live with his parents when he was 11.

It was commonplace, he told the jury, for his mother to verbally, physically or psychologically abuse him if he failed to meet her demands for perfection.

This time, he said, he believed she wanted to kill him.

In his evidence, Li said he never wanted to hurt his mother, telling the jury he loved her.

He said the morning of Friday, March 18, 2011, had started normally at their family home on Lockwood Rd.

“My memory of that day is very blurry and obviously it is very traumatic for me,” he said.

“It was a normal day, nothing out of the ordinary.

“I was supposed to go to university for lectures and tutorials so I didn’t need to go to the shop. I got up, I was supposed to play the piano and I knew that. My mum wanted me to play the piano every morning. I didn’t want to.”

Instead Li said he wanted to do some exercises, as suggested by the instructor at the University of Adelaide aikido club he had joined a couple of weeks earlier.

“I put on my uniform before she got up and did some exercises. I knew I should have been practising. I should be at the piano already.

“At some point she must have got up yelling and screaming. I tried to appease her. There was nothing I could do. There was nothing I could say that would calm her down.

“She just came at me out of nowhere. It happened so fast. At some point I realised she had something in her hand, just going at me. I was totally overwhelmed.

“Although this had happened many, many times before, I knew there was something different about her.

“She seriously wants (sic) to hurt me for what I had been doing, and nothing I could say could reason with her.

“This time I knew she wanted to kill me. I had to fight back. I had to stop her.

“Then everything happened after that. I just can’t remember.”

According to a forensic pathologist, the struggle ended when Li strangled his mother to death, either with his hands or a cord.

He then wrapped her body tightly in three white sheets and left it in the lounge room before mopping up blood from the white marble floor.

Li put his martial arts uniform in a bucket to soak before taking his parents’ Mercedes-Benz sedan to two service stations, where he put in $70 worth of petrol.

The next morning he drove up the South Eastern Freeway but the car developed mechanical problems, forcing him to return to Adelaide.

Li then rang a bus company and Great Southern Railways before going to Flight Centre at Burnside where he waited patiently until he bought a one-way flight to Melbourne.

Li flew to Melbourne at 4pm on the Saturday afternoon and spent the night with a friend he had met through online gaming, Xian Ji.

The next day he booked an apartment, where he met with a male prostitute he found online.

On the Monday he rang Ji, hysterical and incoherent. Ji told the trial his heavily intoxicated friend said he wanted to kill himself.

The following day Ji took Li to a travel agent in Melbourne’s Chinatown, where he tried to buy a one-way ticket to Singapore but was told he could only fly return.

As Li was paying $975 for his ticket, police and forensic experts were swarming over the crime scene at Burnside.

They had been alerted by his father, Jian Lu Li, who had called a friend from China to ask him to check on his wife and son.

The friend climbed through a kitchen window to find Mrs Tien’s body. He called Mr Li, who told him to call the police.

Within hours Li was the prime suspect and a nationwide alert was issued.

However, because of a bungle involving a detective’s mobile phone, Li flew out of Tullamarine Airport early on the Wednesday to Singapore.

A few days later he flew to China.

There he met up with his father, who had tried 120 times to ring Li while he was in Melbourne but got no answer.

Li spent three years with his father, other relatives and on his own before his visa ran out and he was apprehended by Chinese authorities.

He was deported back to Australia in July 2014, and met at Sydney Airport by NSW detectives dispatched by South Australian Major Crime Investigation Branch detectives.

Among the evidence gathered by the homicide detectives was a laptop used by Li in Adelaide and Melbourne.

Along with multiple searches for methods of killing somebody, committing suicide and gay escorts in Melbourne, the laptop contained search terms such as “avoid police” and “track mobile”.

Justice Kelly told the jury that none of this — from Li cleaning up the house, to leaving Adelaide for China, to the search terms found on his computer or his concealed homosexuality — could prove that he had murdered his mother as defined by the law.

The case against him, she said, was entirely circumstantial. It was the role of the prosecution to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Li had deliberately killed his mother or had wanted to cause her serious bodily harm.

In his closing address, Mr Pearce told the jury Li had told a litany of lies during his evidence, “which was, by and large, a nonsense.”

Li had pretended to have lost his memory about what had happened “so he didn’t run the risk of being pinned down on anything specific”.

“By saying he had no memory was a convenient way to avoid being tested on the nuts and bolts of what was going on,” he said.

Mr Pearce said the forensic evidence clearly showed Li had taken at least four minutes to strangle his mother to death during a “prolonged struggle” which inflicted 53 injuries to her arms, neck and throat.

“Has he told the truth? He has he told us the truth about why it was they ended up in physical conflict in the lounge that morning?” he asked the jury.

“Has he told us the truth about the circumstances that led to the altercation that saw a multitude of injuries inflicted on Ms Tien?

“Has he told us the truth about how it was his hands, or indeed a ligature, was put around her neck and compressed around her neck until she died?’

Mr Pearce said the objective facts told the jury that Ms Tien “fought for her life”.

“She fought for her life as her son held either his hands or a ligature around her neck until she died,” he said.

In his address, Li’s lawyer, well-known criminal barrister Kevin Borick, QC, told the jury that there was “no clear evidence of intention”.

“There is no direct evidence of intention to kill in the sense that Daniel had ever said to anyone ‘I am going to kill my mother’ or he took a gun or knife or anything like that,” he said. “No one knows what really happened.”

Nobody, that is, except Wei Li.

He will face sentencing submissions on Thursday, when it is expected a psychiatric report will be requested by Justice Kelly.

Unlike murder, which carries a minimum sentence of 20 years in prison, manslaughter sentences can range from suspended jail terms to life imprisonment.