Quest for answers in the chemotherapy bungle is over, but the victims and families’ wounds will never heal

Imagine you’re diagnosed with a disease that will likely kill you. You put your faith in the specialists and prepare for the fight of your life, but you’re failed by lapses in treatment — do you sue? Penelope Debelle examines this shameful chapter of public health.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- March 2019: The chemo blunder inquest findings

- November 2017: Inquest opens

- June 2015: When the story was first broken

Imagine being diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia, a disease that will very likely kill you. You put your faith in the hands of the specialists and prepare for the fight of your life.

The treatment is hard and unpleasant – you must be poisoned enough to kill the cancer without it actually killing you. Once this ordeal is over, you are told – in some cases clumsily and in one case maybe not at all – that you were given only half the recommended chemotherapy during a critical phase of the treatment.

Do you sue?

The 10 Adelaide leukaemia patients and their families caught up in this nightmare faced one insurmountable hurdle and it brought the story to me in the first place. It was never going to be possible in a courtroom to prove that a less than ideal chemotherapy dose caused any one of them to fall ill again, and in four cases, die.

The day in August 2015 that my story about the underdosing scandal broke, the then head of cancer services for SA Health, Dr Peter Bardy said – correctly but to the enormous hurt of those who were ill – that the cure rate was only 30 to 40 per cent. What he was saying was that if all of them got the treatment they should have, six or seven of them would still get sick again and perhaps die.

With odds like that, court-ordered compensation was unlikely. Maybe the media could help? As it turned out, the resulting public attention was the reason the patients were looked after properly at all.

In early May 2014, Chris McRae, a marriage celebrant and member of a bush band that played for cruise ships (he was on tea-chest bass) went to the doctor after suffering dizziness two days in a row. He had blood tests and a bone marrow biopsy and went back expecting to be told he was iron-deficient.

“The doctor turns away from the computer screen, looks at me, in prayerful pose, and says ‘it’s not good news, it’s bad news. You have acute myeloid leukaemia’,” McRae told me in May 2015 at his Vale Park home.

By then, he was sick again and had so many grievances, it was hard to know where to start. In mid-2014, he went through chemotherapy at the RAH, signing waivers that acknowledged he may well die.

“Obviously we wanted to fight as hard as we could and we went into it knowing we would give this the best shot that we had,” his daughter Rebecca Emery said.

McRae struggled during treatment but by November 2014, he was in full remission. He was told that patients often relapse but it was possible he would live a relatively normal life. He had lost a lot of weight but started rebuilding fitness, walking on Linear Park and planning a cruise in the Pacific islands with his wife.

In February 2015, his blood count started showing troubling signs and he went back for bone marrow biopsies that confirmed something was wrong.

In March, the family met at the RAH with a junior specialist they didn’t know, Dr Anya Hotinski, who told him he had relapsed.

“Then she concluded by saying, ‘unfortunately I have to share some other information with you’,” McRae told me. “I was thinking, have I done something wrong?”

In a state of some distress herself, Dr Hotinski told the aghast family that McRae was one of 10 patients over seven months who had received only half the intended dose of chemotherapy during the consolidation phase of treatment.

He received the correct measured dose but it was administered daily instead of twice daily, a factor of timing that not only reduced the overall amount but prolonged the gaps between treatments, which diluted its effectiveness.

No one knew it then but from mid-January when the mistake was uncovered, there was turmoil behind the scenes at both the RAH and the Flinders Medical Centre, which used the same database for the drug. The head of haematology at the RAH, Professor Ian Lewis, was in a career-damaging meltdown and on the day the McRaes were told, he went to Sydney and left a junior doctor to deal with the mess.

Four years later, Deputy Coroner Anthony Schapel would say this about Prof Lewis and his actions on the day.

“Associate Professor Lewis acknowledged, appropriately, that he feels ashamed and embarrassed,” Schapel said. “Indeed, it smacks of a complete abdication of responsibility and of an avoidance of a difficult issue due to a lack of fortitude.”

In other words, he froze – like a kangaroo in the headlights, in Lewis’s own words – and was too scared to tell McRae himself.

When Dr Hotinski became overwhelmed during the meeting, she asked another senior doctor, Dr Agnes Yong, for help. Dr Yong entered the meeting and told the family that the dosing error (which she had helped to uncover because she knew the correct dose) probably didn’t matter in terms of whether he had relapsed.

Behind the scenes, Dr Yong, like Prof Lewis, was also doing little. She told Schapel during the inquest she was from a patriarchal Chinese culture where women didn’t raise problems with their bosses. Schapel rightly dismissed that as professionally unacceptable. “She was on the back foot and had her guard up,” Emery said of Dr Yong in 2015. “We felt right from the get-go that she was enormously defensive.”

McRae said he remembered Dr Yong reciting to him the high chance of fatality with acute myeloid leukaemia, which made the family upset and angry. Cancer patients live with the odds every day but it’s not what you focus on when you are fighting to recover.

“She didn’t apologise,” Emery said. “I kept going back to the fact that the relapse rate did not address the breach that had happened.”

As McRae became sicker, the family began private negotiations with the RAH about compensation that would acknowledge the mistake and its possible impact. Emery said she was flabbergasted that an error of such gravity could even happen.

How was there not a three-step process that would have spotted the mistake at the outset? There was but nobody followed it for long enough to read the line that omitted the vital but innocuous initials “bd”, meaning bi-daily infusions.

It was clearly a horrendous stuff-up with potentially life-threatening implications and the McRaes sought legal advice.

After reviewing the circumstances, a no-win no-fee firm turned them down because a court case would not succeed. At that point, they decided to bring the media in so at least the public would know.

Having spoken to the McRaes in May 2015, I held the story until August after they were offered – insultingly, I thought – $5000 by the RAH, which they clawed up to $9000. When I approached the office of Health Minister Jack Snelling in late July, no one was surprised to receive my call; they had been ready for months waiting for the story to break.

“We are very sorry,” Snelling said in a statement while pointing out that incidents such as this were rare.

At this point, the Government hoped that was it.

Early the following week, my phone rang and a voice said “Hello, I’m one of the 10. My name is Andrew Knox.”

Initially, he wanted to say only how upset he was at the dismissive way the Government had responded, which deepened the distress for him, and his wife Jayne.

“I am disgusted with the way the politicians have handled this, the way they have politicised it and made light of it,” he said.

In conversations the next day, he mentioned in passing that he was given the wrong treatment at Flinders Medical Centre on January 22. That triggered an alarm because by then I knew the mistake was discovered on January 19. Did you keep diaries, I asked? He did, and sent through a personal record of treatment that showed beyond doubt he was treated at least two days after his specialist at Flinders should have known.

Chaos then broke out. The Government had lost control of the story. The narrative shifted from the initial mistake to how it was managed – was there a cover-up? – and an inquiry was ordered, headed by Professor Villis Marshall, the chair of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare.

Knox was personally devastated to think the mistake should have been corrected before his final treatment. “That clearly has to have put me at much greater risk,” he said.

The response of the doctors and clinicians was now a focus and it would take almost four years and seven inquiries for the dust to settle. The Coroner’s report delivered last month said, sensibly in retrospect, that there should have been a royal commission at the outset.

After the inquiry was launched, the question of compensation fell to the Government. Snelling, who said later his biggest career regret wasn’t coming clean on the chemo bungle when it happened, promised to make sure any claim would be quickly and readily settled.

Premier Jay Weatherill undertook that his government would be a model citizen, meaning it would meet its compensation obligations respectfully and without delay.

What a joke. There was a total disconnect between what the Government was saying and what was going on. I discovered from Knox, a former industrial relations advocate who kept meticulous files, that apart from a general reluctance by the Government to disclose information and documents, its insurers were playing hardball. They were telling the patients and their families – Chris McRae had lost his battle in November 2015, six months after I first spoke to him, Johanna Pinxteren was also dead – to “lawyer up” and make a case for compensation.

This meant tracking down medical records and arguing a legal case for damages. It was daunting, arduous, expensive and cruel, and the opposite of what the Government had promised.

In my conversations with Knox, he told me about another of the 10, Bronte Higham, who had been treated at Flinders Medical Centre at around the same time as him.

In fact, Higham’s second to last and final chemotherapy were on January 16 (the day the mistake was discovered by a pharmacist at the RAH but not confirmed by the senior doctors) and on January 18 (the day before a correcting email was sent and ignored).

Bronte was painfully sick again and in April 2016, he was told he had between a couple of weeks and a few months left to live.

He decided to do something that was heartbreaking and brave; to appear in public before the SA Parliament’s Select Committee into Chemotherapy Dosing Errors.

He was an ordinary man with no public profile but after discussing it with his wife Ricki and their adult children, he would speak up before the committee. He shared with me first what he planned to do.

The headlines that Saturday were so confronting I felt dreadful when I saw them, wondering how he and his family must feel seeing in cold, hard print “Say Sorry Before I Die” with the poster “Dying Victim Blames Hospital Error”. He took it with courage and stood up the next week before the parliamentary select committee, calling himself “a dead man walking”.

He asked for two things – an apology, and compensation for his family before he died.

Within 24 hours, Weatherill had intervened (from overseas, he was in Malaysia) with a promise that offers of compensation would be made to the victims or their families. There would be no need for lawyers, arguments, or bundles of documents.

The figure solidified over the next couple of days; $100,000 for each of the 10. Bronte died a few weeks later, in August 2016.

Most of the seven reports and inquiries that followed (not all were made public) condemned the management and culture in sections of the RAH and to a lesser extent the FMC, as dysfunctional, appalling and woefully inept. Safety procedures weren’t followed and when mistakes were made, few people did what they were meant to.

Schapel rightly called out the utter hypocrisy of those who tried to blame their shoddy behaviour on lack of training. “It does not require any training to know that when an error has been committed in any professional walk of life, frank and immediate disclosure is called for,” he found.

In other words, if you’re a half-way decent human being, you use your common sense and report it.

His report did not dwell for long on the failures of Prof Lewis and Dr Yong, who were stood down in May 2017 from the RAH after SA Health received recommendations from the professional regulatory body AHPRA.

Their failings were made apparent during the inquest and at some point – we don’t know when and SA Health still won’t tell us – they left their government jobs for private practice. Schapel focused on the effect of the underdose on the four dead patients, which had grown to include Bronte Higham and Carol Bairnsfather, and also encompassed the living Knox, who relapsed on his birthday in late 2016.

The complexity of the pharmacological and medical evidence the inquest dealt with seemed overwhelming and the court’s ability to manage it was a credit to them.

Schapel’s findings about cause and effect were nevertheless like the closing of a circle. He was unable to conclude that any of them relapsed or died because they were under dosed.

“I do not believe that it is possible for this court to conclude in any of the five cases … that any remission period, or period of overall survival in the case of the four deceased, was significantly foreshortened,” he found. It was also equally impossible to conclude that they were not.

Ironically, it was Knox who was the fittest at diagnosis, who probably lost the most by missing that first opportunity for full treatment and possible cure. Knox went to Melbourne last year and underwent a gruelling stem cell transplant, courtesy of a German donor, and recovered, but with residual nerve and other damage.

Even in his case, Schapel could not say more than there was “a very grave suspicion” that it acted to his detriment. But of all of the 10, Knox was the one with the best chance of being cured at the start. That didn’t happen and he will forever blame the substandard chemotherapy dose.

Acute myeloid leukaemia is a devastating illness that necessitates drastic treatment.

That of itself should have demanded from all the treating doctors and clinicians the utmost standard of care.

A specialist from Melbourne who has been treating patients like this for 35 years told the inquest he found the treatment no less scary now than when he was a young doctor. “It’s a dramatic intervention,” Dr Stephen Vaughan said. “You wipe out their normal bone marrow for two to three weeks and you have got to undertake to keep them alive during that period.”

Without it, the patient will certainly die and with it, they might live, but the doctors had to be at the top of their game.

“When you do scary things you have got to assure yourself you are doing – you are following the rules exactly. And attention to detail is important,” Dr Vaughan said.

This heightened need for care passed our doctors by. In Adelaide in 2014, a mistake was made by someone on a Friday afternoon who was in a hurry to go on leave and the procedures designed to pick the mistake up failed because people around her couldn’t be bothered or were too impatient to do their job and check. When the mistake was found at the RAH, a disturbingly banal correction was emailed to the FMC – whether intentionally downplayed or not, we cannot say for sure – and at the other end, no one at Flinders bothered to read it either.

The welfare of the patients came a poor second to laziness, arrogance and self-preservation.

The emotional strain of falling sick and then discovering you weren’t given the best shot at recovering was an immeasurable burden on the people we know of like Bronte Higham, Chris McRae, Andrew Knox and their families.

Of the 10, it appears at least seven relapsed and of these seven, four died, in line with Bardy’s original prediction. It was of no comfort to know this because each one feared they were sicker than they should be because the South Australian specialists had so badly let them down.

“This in and of itself is a truly dreadful thing,” Schapel said.

It was a shameful episode in South Australian health care which you would like to think will never be repeated.

But then who would have thought it could even happen at all?

TIMELINE TO A TRAGEDY

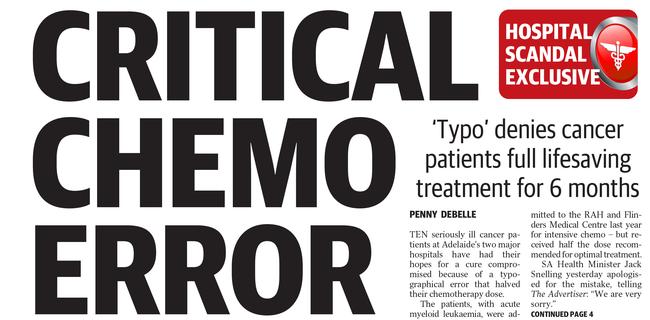

JANUARY 19, 2015: A clinician discovers that chemotherapy doses for leukaemia patients are incorrect due to a typographical error. Ten patients have received only half doses between July 2014 and January 2015.

JUNE 23: Patient Johanna Pinxteren, 76, dies.

AUGUST 1: The Advertiser reveals the underdosing bungle.

AUGUST 3: Health Minister Jack Snelling says “no one has died’’ and Professor Peter Bardy says “they’re all still with us”.

AUGUST 5: Inquiry ordered after The Advertiser reveals one patient wrongly dosed at FMC three days after the mistake was uncovered at RAH.

NOVEMBER 27: Inquiry finds significant clinical governance failures, failure to follow guidelines in using non-standard protocol, inadequate supervision, failure of certain clinical staff to report and lodge the incident, tell patients what happened, or respond clinically.

NOVEMBER 27: Andrew Knox reveals he was one of the 10 patients.

FEBRUARY 8, 2016: Eight clinicians involved in the scandal are referred to the national regulator for potential disciplinary action,

FEBRUARY 24: Legislative Council select committee established.

MAY 28: Bronte Higham tells The Advertiser he has weeks to live and is still waiting for an apology and compensation.

JUNE 1: Premier Jay Weatherill promises offers of compensation will be made.

JUNE 6: Offers of $100,000 sent to victims with the promise that legal fees will be paid.

JUNE 8: One family docked $18,000 for previous settlement, legal fees not paid.

JUNE 11: The head of SA Health, David Swan, resigns. RAH head of cancer Dr Peter Bardy has also resigned.

JUNE 30, 2016: Deputy State Coroner Anthony Schapel announces a hearing into the deaths of Mrs Pinxteren and Christopher McRae, 67, who died on November 22, 2015.

AUGUST 8: The inquest is broadened to include the death of Mr Higham, 67, who died on August 6.

SEPTEMBER 15: A report by the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care finds that the bungle was a “disturbing and indefensible failure in clinical governance”.

DECEMBER 13: Mr Knox, 68, learns that his cancer has returned, meaning that all victims of the underdosing have either relapsed or died.

NOVEMBER 2017: Parliamentary Select Committee slams SA Health for its culture of blame, fear and inertia. Later that month clinicians start giving evidence to the Coroner’s Court about their role in the scandal.

MARCH 2019: Coroner’s report handed down.