South Australia Governor Hieu Van Le relives his harrowing escape from war-torn Vietnam

A SINKING boat, no compass, croc-infested waters and threatened by machine guns – SA Governor Hieu Van Le relives his escape from Vietnam with wife Lan and the moment he feared he’d lost her.

HIEU Van Le bursts into ironic laugher as he describes the calamitous situation which caused a family acquaintance to have little chance of escaping the punishment of the North Vietnamese.

His name was on the delivery manifests of millions of tonnes of US munitions when the rampant communists overran his regional airforce base in 1975 towards the end of the Vietnam War.

“Because he was so senior, all the US bombs for the area had to have a name on them for delivery, and when the North Vietnamese found the paperwork it all had his name on it,’’ Hieu explains.

“They found this officer had taken possession of all these tonnes and tonnes of bombs, and they said ‘who is this guy?’ and they chased after him and he went on top of the wanted list.’’

It is the sort of laughter you hear when the alternative would be tears for the man who, after the end of the Vietnam War and discovery of the damning paperwork, went on to spend more than a decade in a North Vietnamese “re-education camp”.

I hear the same laughter later when Hieu recalls how wife Lan was crippled by toothache at a crucial moment during their escape; when he describes how the overloaded boat which was to take them on their open-sea voyage capsized immediately they boarded; and again when he explains the hopeless optimism of their refugee escape plan, to sail out into international waters where they would “inevitably” be picked up on a mythical container-ship super highway.

It is spontaneous and genuine laughter, but somehow out of place. It is as though, sitting in his luxurious Government House home on North Tce, Adelaide, the memories of those desperate days have become so surreal he can only process them with humour.

Recollection of the family friend’s ordeal at the hands of the North Vietnamese seems to give His Excellency the Honourable Hieu Van Le AO, Governor of South Australia, pause for thought. Spontaneous laughter is one of his most defining characteristics, but darkness quickly falls and his head drops a little when he recalls the war.

“Somehow I feel extremely lucky,’’ he announces in matter-of-fact fashion, before trying to condense the horror of his chaotic childhood.

“Growing up there all I saw, all my memories were about killing, about shootings, about bombings and there was not a single day I could feel safe. But for some reason I came out of that quite all right,’’ he explains, now in sombre tones.

“Sometimes the violence would just appear next to your house in the village, or during school times when suddenly the school would be full of refugees fleeing the fighting in the countryside.

“One day we all had to stay home because some rockets had destroyed part of the school. I had a lot of childhood friends who were just gone, very often, many of the others were disabled and lost limbs.’’

It was the sort of detail I had come to Government House to hear, but I feared these words would at any moment be extinguished, smothered by international diplomacy, royal protocol or an over-zealous staffer. An hour and half later they were stopped only by repeated text messages from social worker and wife Lan Le, wondering when the overdue lunch with her husband would finally start.

My frustration, I tell His Excellency from the beginning, is that the legend of Hieu Van Le – embraced by the Australian public and media – always begins in 1977 when his refugee fishing boat limps into Darwin Harbour and is greeted by the dinkum Aussie who holds up his can of beer in salute and says “G’day mate’’. South Australians seem to have a sense of ownership over Hieu’s life if they focus on his arrival, integration, rise to be a multicultural spokesman and then the Queen’s man, or the fact that his two sons, both pharmacists, are named after Australian cricketers Sir Donald Bradman and Kim Hughes.

MY INTEREST begins much earlier. Forty years ago I was just nine years old when Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War ended.

I grew up between the propaganda fairytale of John Wayne’s The Green Berets and the American self-loathing of Oliver Stone’s Platoon. The war was a large part of an Australian childhood of the era, but the closest I came to the reality was being conscripted by my parents as police baton-charge fodder in anti-war protests in Brisbane. Since becoming aware of the public Hieu Van Le, when he was appointed chair of the South Australian Multicultural and Ethnic Affairs Commission in 2006, I have wondered at his place at the epicentre of one of the great ideological conflagrations of the 20th century. The “running away” from his homeland, as Hieu calls it, also fascinated me. At last I have an audience with the Governor to hear the stories first-hand.

I had always assumed Hieu was simply a creature of the south, who fled political persecution following the communist victory in 1977. Reality is far more complex. His life story is more south by circumstance than design, sandwiched as his birthplace was between north and south in the ill-fated province of Quang Tri. “I was born in the harshest part of Vietnam that nature can create for anyone,’’ Hieu explains. “It is the narrowest part between north and south where the climate is very extreme. We have floods, storms, cyclones every year. The soil is terrible and is all rocks and clay so there is only agricultural industry, and living off the land.

“So life in the beginning was harsh.’’

But if nature was bad, geo-political circumstances were worse. One day early in the mid-1950s Hieu’s mother Hanh was contacted to say his father had been killed fighting the French colonial forces.

“One day Mum, who was fully pregnant with me got the message that he was gone. That was all we knew. Thousands of people were killed every day and there was no regular army organisation,’’ Hieu says. “He was in the resistance and it wasn’t a regular army to get more information from.

“For every young man and some young women, you were either on one side or the other fighting against the French or working for the French.

“We were all very proud of him but as happens there were so many people dying that the country just took their deaths for granted and they became victims of the circumstances.’’

The death of the family breadwinner pitched Hieu’s mother and two brothers into a daily battle for survival. “We struggled through with all sorts of labouring and works and selling things,’’ Hieu explains. “Even people with good intentions and a lot of land could not survive on that land.’’

The exit of the French and the safety of being declared in the demilitarised zone between the battling ideologies of the north and south by the Geneva Accord of 1954, was short lived.

Within years Quang Tri was again brutalised by war. If Vietnam was a football oval, Quang Tri was the centre circle, mauled continually as both sides contested the small patch of dirt.

The Americans based their operations there because of the strategic central location, and as battles raged the cities and towns of the province, like Khe Sanh, became household names in far off countries which knew little of them.

Beginning as part of the south, the province was the scene of intense battles with communist troops by 1967. During the 1968 Tet offensive battles raged throughout, and again during 1972, which was dubbed the “Summer of Fire” by the Vietnamese people. The guns only fell silent in March 1975 when the north pushed south and soon won the war.

Quang Tri also has the dubious distinction of being the most contaminated after the war by unexploded ordnance. This included some of the 7.2 million kilograms of unexploded bombs out of 707 billion kilograms dropped on the country. The national death toll from this alone is more than 7000 since the war finished.

The Our Lady Mother of La Vang church, several kilometres from where Hieu lived – and later recognised as a Basilica by the Vatican – became a metaphor for the failure of the DMZ.

“There is a hill and top of that hill is a church built to mark the appearance of the Virgin Mary back in the 1600s. And that church became very famous during the war because it became the centre of much conflict,’’ Hieu explains. “It was completely destroyed except for the crucifix and the bell tower.’’

The war was ever present in the village. “It was so bad that you didn’t even have to get the information from the media because it was your friends and neighbours. On your way back from school there would be a funeral, ambulances flying past and so on,’’ Hieu says. “We had BBC radio and the Voice of America, but the reality was all around with friends, relatives and neighbours dying today, tomorrow and after.’’

Older siblings, a 10-years-older brother, and a 15-years-older brother (names withheld), provided some relief for the family when they became old enough to work.

“Mum worked very hard as a labourer and she had a little stall selling food, and we had relatives help us out with family savings but we were very poor,” Hieu explains. “But when my brothers were finishing school, and while they studied, they tutored other children and then one became a teacher and the breadwinner of the family.

“However, like all young people in the south, both my brothers were eventually made to do military service. Mum always pushed us to try hard in our education and taught us that it didn’t matter how poor we were as long as we got a good education, and it was the only way to achieve in life in those circumstances.”

There were other motivations.

“By Year 10 if you didn’t pass the exam you were sent off to the army, and came out six months later dressed up in the sergeant’s uniform, and if you didn’t pass Year 12 you became an officer. The class just became smaller and smaller,’’ Hieu says. “Some would then disappear, be killed, or come back in wheelchairs or with scars.’’

From the hundreds who had attended the school only around 30 remained when Hieu returned in 2009 for a reunion.

MIRRORING the history of the Vietnam war, Hieu and his family gravitated southwards to the relative safety of a large regional city by the time he started high school. “Mum was getting older and life harder and harder as the war escalated in Quang Tri, so if you could run and had anywhere to run to, you ran,” he chuckles.

University in 1971 was another change of scenery, this time at the private campus of the central-southern highlands city of Da Lat. As a star student, school captain, and student representative for the last three years of school, Hieu knows he could have made a more economically sensible decision on study topics at university than the path he chose.

“It disappointed my mum and family,” he admits. “Most people with good marks wanted to be a doctor or a dentist or a pharmacist but I chose economics simply because I saw the devastation of poverty and I wanted to do something to improve the economic conditions for the Vietnamese people. That was my dream.

“I was a leader within the student movement, but it wasn’t party politics. We organised social activities, did charity work and helped the refugees running away from the war.”

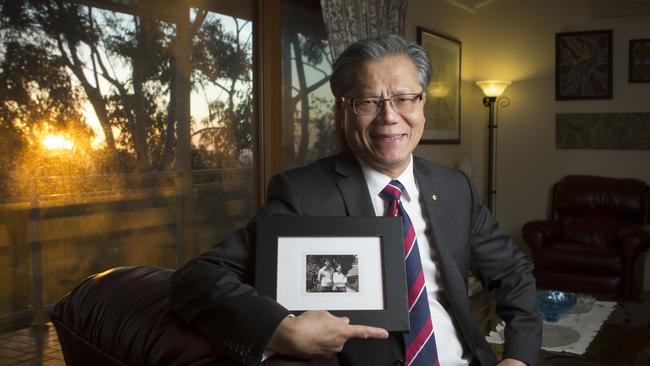

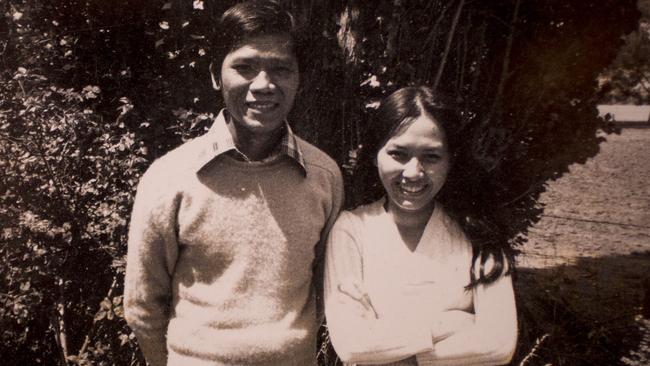

Surprisingly love had found a way in the relative calm of secondary school life in the late 1960s and 1970s. At university in Da Lat it flourished. Hieu had met Lan at high school. They married in 1977 in secret when it had been decided they would make the perilous journey to Australia.

“Because I was active in the student movement and she was into musical things, a singer, we met at some of those performances,’’ Hieu remembers. “Lan was full of life. I had a group of friends and one of them was a boyfriend of one of Lan’s friends so we had get-togethers.”

Nothing was easily organised in the chaotic country in the early 1970s, and even a get-together for friends was lucky to happen. “I remember it was Christmas 1972 and we had a musical Christmas party, and Lan was there. It was the peak of the Vietnam War and we were so lucky to get together in one spot, and I sang John Lennon’s Imagine.

“It is so poignant and in fact he had written that song because of the war in Vietnam, and I think that is how Lan fell for me.’’

Forty-two years later at Hieu’s swearing-in ceremony as Governor the song was played as a reminder.

After university, Lan and Hieu returned to the larger city where they had attended high school together to be with family, but as the war ended it too was over-run.

“We all fled separately. It was such chaos,’’ Hieu explains. “I arrived in Saigon not knowing what had happened to Lan. There was no communication and the battlefront was right in the city.

“I was lucky enough to get a seat in the plane, which was the last one out. I took my mother to get her out but the rest of the family stayed. It was all done within a day, and the military pressure was building around Saigon as well.

“There was no way to communicate with Lan so we didn’t even know if she was alive for about a month. Lan’s family was eventually evacuated and we were reunited.’’ With the war ended, the young couple again set about trying to survive.

“It was very difficult because the entire civic system had completely changed. The uncertainty was so big a lot of companies left and it was very chaotic,’’ Hieu says.

“It is amazing how you survive in that chaotic post-war period. You cannot plan for the future.’’

IT IS easy to imagine how what was left of his homeland was never going to be able to contain Hieu Van Le’s future. Highly intelligent, personable with an infectious laugh, he is a natural leader of people. Square-jawed, big-haired, and with a ready smile, his official photographs look like the cross between cover art for an Asian Mills & Boon novel and a portrait of royalty.

He is articulate in his adopted language in his own way. Hieu has a turn of phrase that transcends language barriers to make him an impressive orator. His official speeches are smattered with moving oratory more suited to US politics than Australia, like this description of childhood at his swearing-in ceremony: “War was part of my life and it has left me with a painful and ever-present soundtrack of my childhood – rockets firing, roaring helicopters hovering overhead as we ran for cover, endless firing of weapons … and the haunting sounds of people suffering.”

Details of Hieu and Lan’s flight are likely never to be revealed, except perhaps in his memoirs, when many of the characters have passed away and his time at Government House is part of history.

He picks up the story again when he embarks upon the boat journey they hoped would take them to safety. Exhaustion from weeks of worry, not eating, a night in hiding and immediate crippling sea sickness set in as the night dragged on.

“There were huge waves when we tried to get from the little boat to the big boat and we just collapsed when we got on the boat. It was a real struggle and I can’t even remember how I got on,’’ Hieu says.

“The next day I started to wake up and I wasn’t really conscious. I couldn’t see Lan and everybody was lying on top of each other, and I thought she had died in the night. I thought she had probably gone and I cried out her name but nobody responded. Later I saw someone pinching my leg and she was laying right there at the bottom on my legs. We were delusional.”

Hieu’s understated version of the ordeal leaves you thinking it must have been much worse than described. “It was a long way”.

“They cooked rice and noodles and we had bread, but there was no toilet,’’ he explains. “We went east for two days. The skipper said ‘I’m just a fisherman – this is as far as I have gone on my fishing trips and I don’t know where to go any more’.”

It was then Hieu realised, as trans-oceanic escapes go, there wasn’t much of a plan.

“The rumour was that once you got out off the coast for three days roughly, you would reach the international waters and it was like a superhighway on the open sea with ships going up and down all the time. So you would be picked up no worries,’’ he says.

“So after three days we thought ‘that’s it, we will start seeing ships now’. Well we circled around for three days. Then the arguments started and everyone had an idea because we had architects, teachers, ex-servicemen, accountants, peasants, and the boat was circling endlessly.

“Nobody had any equipment or maps because if they found out you had bought a compass or something they would be on to you. So I grabbed a piece of paper and drew a map of Vietnam and South-East Asia.

“The skipper showed me where we were roughly and I said ‘look we have been here for three days now and we can’t stay here because we have no fuel and no water and all the kids were crying’. I told them ‘from my geography lessons I think it is about time we moved west because if we keep going west we will run into Thailand or Malaysia’. Oh, what a sight – two or three days later, we started seeing fishing boats with Malaysian flags.’’

B UT their ordeal had only just begun. “We thought, ‘we have done it’. But when we got close to shore a coastguard boat rushed out and pointed their guns at us. We told them we were refugees, and they acted as though they couldn’t understand what we were saying,’’ Hieu remembers.

“We waited and waited and waited and nothing happened so at about midnight they came on the boat and said we could not stay there and had five minutes to leave. I said ‘no’ but they pulled us out for three or four hours out to sea. We kept going back along the coast hoping for more luck but the same thing happened six times. We even went to Singapore, which was worse. They sent a warship with cannons instead of guns.

“Eventually we were out at sea again and the boat gave up and started to sink, the fuel was gone and the water had run out, and by that time I had been nominated as the navigator of the boat.

“I said ‘look if we go on like this we will all die soon. Our last action is to abandon the boat and swim because it will soon be a trap for all of us’. With the last fuel we steered the boat and got into shallow water 50-60 metres from the shore and the coastguard came out again and I gave the order to jump.’’

The boat had left Vietnam 10 days before, and now – within sight of their goal – the Malaysian coastguard had been given an ultimatum to either stop the refugees, arrest them or let them swim for it.

“I remember very clearly the captain of the coastguard telling them to load and fire warning shots into the sky. They became quite panicked,” Hieu remembers. “The boat was almost half way into the water.”

Inexplicably, it was only then that Hieu found out Lan could not swim. “She was the last one in and she was standing there crying. So I grabbed her and jumped in.”

Shallow water ensured all survived, and the defeated coastguard surrounded the landed refugees with barbed wire where they stood. By chance the Red Crescent, (the equivalent of the Red Cross), was operating in the area because of another refugee landfall. Two weeks later a stint of several months at an island refugee camp began. “The local people said to me ‘we were praying for you when you jumped from the boat because that water is heavily infested with crocodiles and only a day before a girl was taken’,’’ Hieu says.

AT THE island camp a boat owner who wanted to sail to Australia heard of Hieu’s navigational skills. “I said ‘I know nothing about navigation, that was just luck’,’’ Hieu says.

“His boat was horrible, it was tiny and the passage is very dangerous, and I told him I would rather stay here. But I ran into a guy who had been a navigator in the navy and he explained to me how to do it.

“I spent about two weeks with him, and Thang (who owned the boat) collected spare parts and materials from all the abandoned boats along the coast. And off we went again with 42 people and a lot more supplies. It took us more than two weeks but everyone survived.’’

The boat first ran into Melville Island and from there Darwin.

“We waited for the coastguard to come out like they did in Malaysia and tell us to go back out to sea,” Hieu says. “But all we heard was the buzzing noise of an outboard motor and the little tinny came out.

“We went past a big ship, I think it was an oil tanker, and I stood on top of the boat and I called out to them ‘excuse me sir where is the nearest police station’ and the headline the next day said I had asked them ‘in nearly perfect English’.

“Immigration met us where we docked and he said in a heavy Aussie accent ‘who are you, what’s your noime?’.”

In some ways family life became normal when Hieu and Lan were able later to sponsor relatives to Adelaide through the Australian Government’s “orderly departure” program.

Other than Lan’s father and Hieu’s mother – who died three years ago after living in Adelaide for many years – other family members to make their way to Australia included Hieu’s two brothers, one of them under his own steam as a boat person himself.

“I had a lot of help from many people, and I am very proud of helping the others over,” he says. “The one thing I feel most pleased about in the end is that my mother could finally know what peace was like in her life when she came to Adelaide, because she never had that before.”