SA’s political landscape in 1969 was a foreign place

The political landscape of 1969 was a foreign place. Back then, we had a politician with the courage to sign his political death warrant simply because it was the right thing to do, writes Andrew Faulkner.

The political landscape of 1969 was a foreign place.

It’s as alien as the Sea of Tranquillity was to those three men as they suited up for the world’s day of days.

Yes, there were Liberal and Labor parties. We had the same two state houses. And universal franchise. (Actually we’d had that since 1895, when women — including Aboriginal women — were given the vote.)

The difference is this: In 1969 we had a politician with the courage to sign his political death warrant because it was the right thing to do.

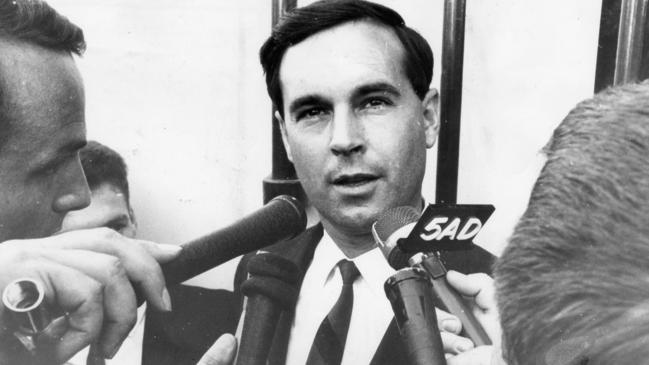

Fifty years ago Premier Steele Hall’s government recognised, accepted and admitted that the state’s voting system was grossly unfair.

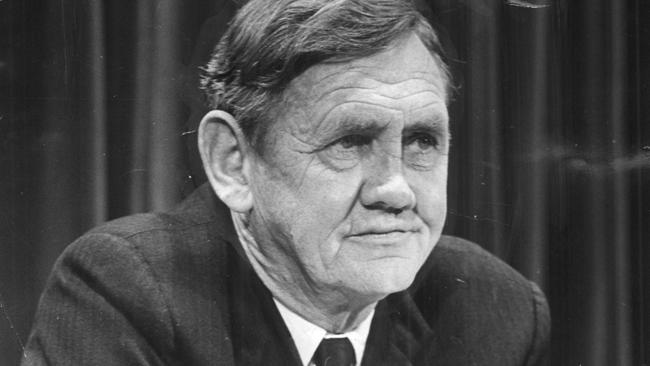

The “Playmander” — somewhat unfairly named after former premier Tom Playford, who benefited from an inequality he inherited but did not design — had been winning elections for the conservatives since the 1930s.

Under the system, South Australia had about twice as many country seats as city electorates.

Some of the country seats had only several thousand voters; whereas the booming city electorates had tens of thousands.

The country seats lent towards the Liberals, the city seats to Labor.

“Who but a fool is going to vote himself out of office?” Mr Playford snapped back at his daughter Margaret when she challenged him to right the wrong.

Mr Hall was, that’s who. He acted where his predecessor sat on his hands. Not because it was easy, because it was right.

He oversaw a statewide redistribution after Labor won 53.2 per cent of the two-party vote but lost the 1968 election.

In the meantime he led a government that clung to power thanks to the support of rural independent Tom Stott.

It was a delicate and fractious alliance.

Mr Stott wanted a dam built at Chowilla, in his Riverland electorate, whereas Mr Hall preferred an alternative plan for a dam at Dartmouth in the Murray’s upper catchment.

The uneasy partnership held together long enough for Mr Hall to pursue policies of increased migration, mineral and natural gas exploration, cutting unemployment — he had whirred it back to the national average after a mid-60s economic downturn — and shoring up the primary production base.

A robust state parliament debated electoral reform, abortion, demerit points for motorists and the MATs plan — an ambitious, and ultimately doomed, project to slash freeway corridors through the suburbs.

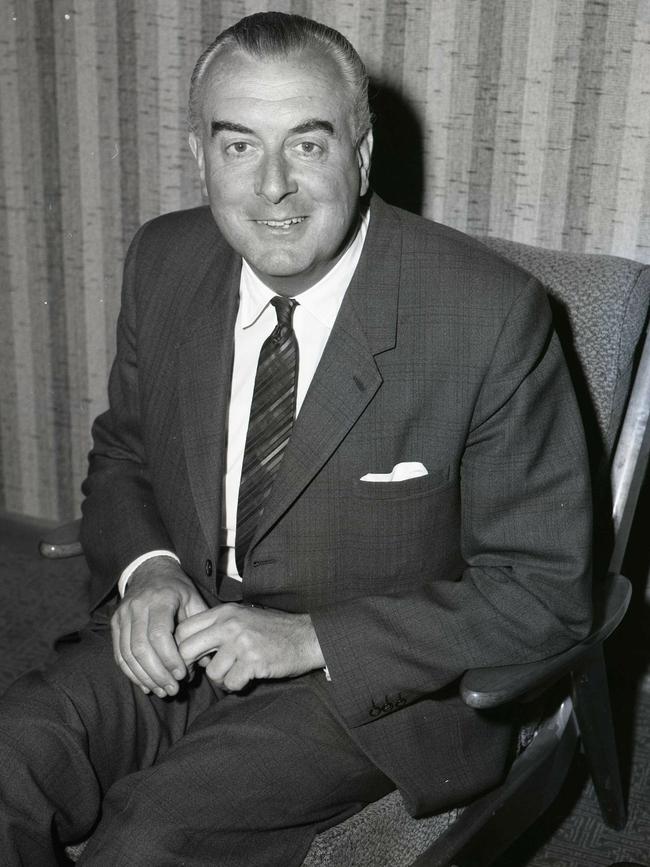

In Mr Hall, 40, and opposition leader Don Dunstan, 42, the state was led by new-age politicians in step with the changing times.

Both were comfortable on television — and looked good on it — and both appealed, in different ways, to the youngest Baby Boomers as they came of voting age.

Mr Dunstan pushed the electoral malapportionment injustice at every opportunity while spruiking policies focused on health, education, food and wine and the arts.

Mr Stott’s decision to withdraw his support in 1970 — over Mr Hall’s refusal to back the Chowilla dam — triggered an election and heralded the dawn of the Dunstan decade.

Federally, the John Gorton government braced for a close election in October.

Gough Whitlam was expected by many to end 20 years of conservative rule.

In June, Mr Whitlam pegged out the ground on which he’d fight the poll — an end to the Vietnam War, an end to conscription, and the “repeal of the penal clauses in Commonwealth industrial law”.

The Labor spin doctors might have put a bit more work into the third plank of that particular election pitch.

In the “more things change” category, one of the leading issues of 1969 was whether Australia could afford new fighter bombers. At $300,000 a pop, the F-111s were pricey, although how that compares with our new Joint Strike Fighters’ $110m a plane is unknown.

The concerns appeared well-founded soon after the first F-111s touched down in Australia.

Structural problems delayed their entry into frontline service, and they never made it to Vietnam.

But given the F-111s didn’t drop a bomb or fire a shot in anger, it could be argued they are our most successful military purchase.

And so the Don’s Party election of 1969 came to pass. Don, Mack and Cooley — John Hargreaves, Graham Kennedy and Harold Hopkins in the film — filled their Eskies with Southwark Bitter cans ready for the big night on Saturday, October 25.

It wasn’t time.

Sadly for Don and his mates, Mr Whitlam lost. But he garnered a big swing, laying the ground for his win in 1972.

The Liberal Country League member for Adelaide, Andrew Jones, was among the many casualties.

Afterwards Mr Jones told Mr Gorton that “not even Jesus Christ could have held Adelaide”.

The election sent a message to Mr Gorton that the war in Vietnam was as untenable as it was unwinnable. On December 16 he said he would bring the troops home.

The announcement was as welcome as it was thin on detail and ultimately hollow, because the last Australian infantryman didn’t leave Vietnam until February — February, 1972.