Major fail: The grand, weird and downright silly major SA projects that never saw the light of day

Floating hotels, cable cars and canals are just a few South Aussie pipe dreams with eye-watering price tags that never got off the ground. See the full list.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They are the grand, weird, and downright silly Adelaide projects that never got off the ground. Some came with eye-watering price tags, many made our eyes water with laughter while others caused us to heave a sigh of relief when the inevitable happened and they were finally scrapped.

In terms of big-picture city and regional planning, Adelaide has been the nation’s dream factory since Colonel William Light mapped out the square mile. But even the great man contributed to our great flops.

It just goes to show, sometimes big dreams can turn into giant nightmares.

We take a look back at some of the major SA projects that might have been but we’re sort of glad never were.

MIKE RANN’S ‘ICONIC BUILDING’

The failure of this idea left some wondering if Mike Rann was just overly fond of talking about an “i-con-ic build-ing”, given the joy he took in his BBC “train-ed broad-caster” quirk of enunciating every syllable in every word.

But sadly for Mr Rann’s grand iconic building plan, the need for the public to throw money at an iconic building less than ten years after the State Bank collapse was never established. A grab bag of possible major tenants perhaps showed Mr Rann was reaching a little. It was to be a concert hall, or a centre for indigenous art, or Australia art or a science centre.

“People have spoken to us about their desires and Adelaide’s need for an iconic building that celebrates our national identity internationally,’’ he said in 2002.

“Perhaps as a concert hall, perhaps a gallery for contemporary art, perhaps a gallery of Australian art, indigenous and non-indigenous, perhaps as a home for the … Investigator (Science and Technology) Centre.’’

In the end the details of the ic-on-ic build-ing were never fleshed out, and quickly shelved after Mr Rann won the 2002 state election.

It wasn’t the only Rann plan Adelaide missed the opportunity to see come to fruition. The Rann government-in-waiting was also set to “halve homelessness” which, after it was established this would cost too much, quickly became halving the much smaller number of people “sleeping rough”.

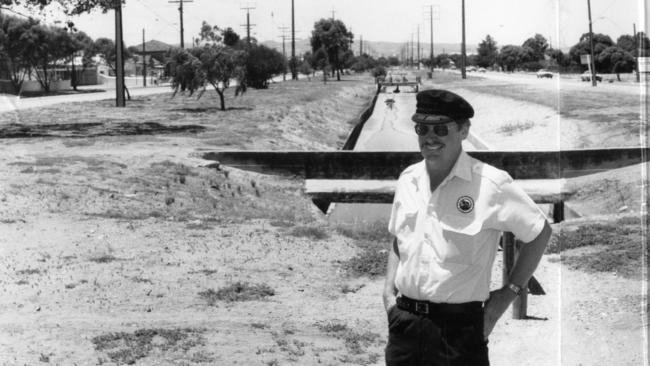

PORT ROAD CANAL

The grandmother of all Adelaide failed projects was a plan to build a shipway to move goods by water along the centre of Port Road – land that to this day is still bereft of much development. It was the idea of one of the city’s founding parents, Colonel William Light, who despite his revered status, perhaps began the great tradition of Adelaide ideas that go nowhere.

At least the prerequisite for the grand canal idea was done properly. The road is 60m wide for the 12km length and a large median strip was left for the future waterway.

But in 1851 it was reported in one local paper that the idea had “startled” the “plodding citizens” of Adelaide and so, instead, the Port rail line was born, a far cheaper and more practical option to quickly move people and goods between Port Adelaide and the city.

But like many ideas on the failed Adelaide wish list of projects, what we finally ended up with was far less visionary and fun than the original canal concept.

If it had been built, we can only imagine the long list of other exciting projects that would have been in development at Port Adelaide, which is still a bit of a hodge podge.

On paper, and in artist’s impressions over the years, Port Adelaide would by now easily rival the Australian best-practice of port redevelopment, Fremantle.

Oh well, it’s water under the bridge now.

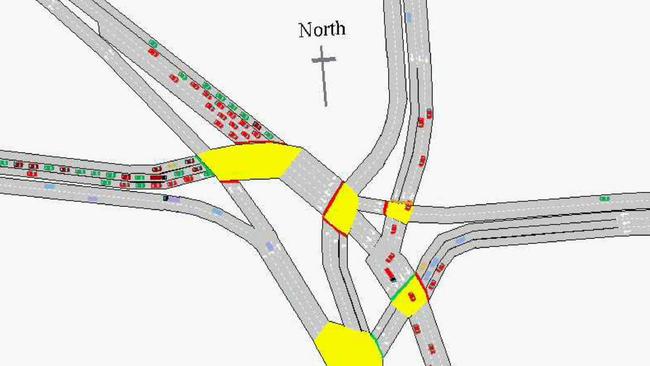

BRITANNIA ROUNDABOUT TUNNELS

For decades solving the problem caused by traffic jams and hair-raising near-misses at the Britannia roundabout has been a bridge too far for planners and politicians.

Odd, really, because at other major intersections, in every city in the developed world, the solution seems simple. The intersecting roads are either separated by a bridge or an underpass, or traffic lights to control the oncoming vehicles.

And so as the new millennium dawned, salvation for frustrated motorists seemed to finally be at hand with one such simple solution.

In 2004, the government promised an $8.8m intersection upgrade with traffic lights. But 66 trees would have to go, and worse 3000sq m of Parklands.

Being Adelaide, the plan was of course rejected.

After ten more years of no proposed solutions, engineers officially reinvented the wheel and convinced the state government to fix the notorious roundabout … by building another roundabout.

We guess that’s a roundabout way to fix the problem.

Alas it can still take up to ten minutes to traverse the dual roundabouts in peak hour and still feels like you’re taking your life in your hands when you’re forced to run the gauntlet.

SOUTHERN PARKLANDS LAKE

Perhaps the greatest source of Adelaide projects that never get off the ground is Adelaide City Council itself.

With only the CBD and North Adelaide to look after, it sometimes seems like the little-picture experts are doing their best to make sure big-picture plans never happen.

In 1998 the city was to have a large aquifer-fed lake in the south parklands, but a sod was never turned on the idea.

As a candidate in 1999, Lord Mayor hopeful Michael Harbison planned a massive expansion of the Torrens Lake. He won, but the lake plan was lost.

Another hopeful, Stephen Yarwood, had much bigger plans around ten years ago. By 2023, Mr Yarwood predicted, the CBD population would swell to 40,000, trams would crisscross the entire city centre, cyclists would be one in every ten commuters, and electric vehicles one in every five vehicles on the roads. Most unlikely was his idea that homes would be built on the top floor of carparks.

Fat chance any of these ideas would get off the ground, of course.

LE CORNU SITE REDEVELOPMENT

With the work well underway, the former Le Cornu site can finally be taken off the list of failed Adelaide pipe dreams.

Adelaideans have been talking about the site at family BBQs and around water coolers since it first became available in 1989.

It is one of the longest NIMBY-stymied projects in Australia, slap bang next to one of the busiest roads in a capital city.

Over the decades of debating a possible future for the site, Adelaide children have been born, grown-up, and celebrated their 30th birthdays before the Adelaide City Council was able to do anything.

The problem? The site also sits in the middle of the only suburb run by the CBD council. It has been unable to reconcile any project with North Adelaide’s vocal high-income earners, bluestone villas and cottages.

The first plans for the 7535sq m site were rejected in 1991, when a retail complex – already approved – was knocked back, beginning years of argument, court challenges and appeals over building heights.

In 1997, it was going to be cinemas and a carpark.

In 2005, that changed to a luxury hotel, retail shops, apartments, restaurants and a cinema when Makris Group bought it.

Two years later, the state government took control of the site from the city council, promising to fast-track development.

The global financial crisis undid that, then a 2012 joint venture between Makris Group and the late billionaire property developer Lang Walker fell over in 2013.

In 2014, Makris Group revealed new plans for a $200m, eight-building shopping and apartment complex, adding a luxury Sheraton Hotel in 2015.

In 2021, Commercial & General, led by North Adelaide resident Jamie McClurg revealed plans to partner with the City Council for a $250m redevelopment of the site, featuring three high-rise apartment towers above a two-storey podium comprising speciality shops, cafes, bars, restaurants, commercial offices, consulting rooms and an outdoor plaza.

And work on the project officially began in 2022. Hallelujah.

GLENELG TIDAL WAVE IN THE 1970s

Not strictly a major project, but we reckon this moment in SA’s history still snugly fits into the category of big things that were meant to happen in Adelaide that just didn’t.

In 1976, Melbourne housepainter and self-proclaimed clairvoyant John Nash convinced thousands of people to go to the beach and wait for a tidal wave they all really knew wasn’t coming.

Nash believed he’d had a vision of Adelaide being consumed by a tidal wave and earthquake, at noon on January 9, 1976.

The publicity caused panic, with some people reportedly selling their homes, and others literally heading to the Hills and Riverland on the day, just in case.

It was said coastal properties were sold off, businesses reported a lot of sickies on the day and hotels saw a drop in occupancy.

Even the BBC sent a TV crew to Glenelg. You know, just in case.

About 2000 people headed to Glenelg, to watch the end of the state.

Advertiser columnist Rex Jory, who wrote about the event in 2006, headed down for the party, saying “the mood of the crowd was somewhere between hysteria and hilarity”.

Then-premier Don Dunstan joined in, appearing on the balcony of the Pier Hotel and told the crowd nothing would happen.

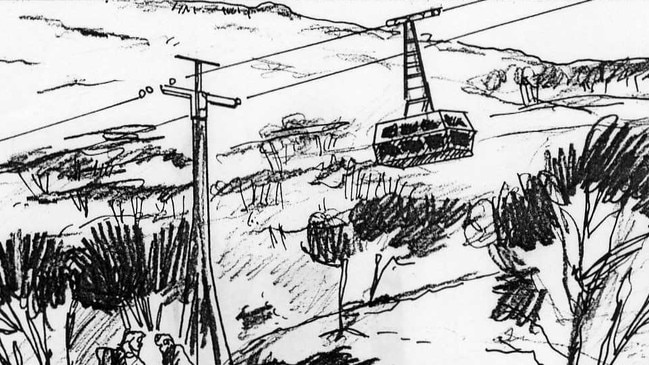

ADELAIDE HILLS CABLE CAR

Cable cars can go where no other land-based human vehicle can. That doesn’t mean they are a good idea when planners are confronted by gentle slopes already serviced by buses, cars and trains.

This may explain why for almost 40 years, plans for a cable car to the Adelaide Hills have never happened.

In 1986 a 6km cable car was to run from the eastern side of Beaumont to just below Mount Lofty Summit, stopping at Waterfall Gully and Cleland wildlife park along the way.

It would have ended at a station inside a 200m communication tower, the central feature of a tourist centre incorporating a 100-room hotel, three restaurants and a kiosk, costing about $140m in today’s money.

The plan included a revolving restaurant, a viewing platform, and restoring St Michael’s Anglican monastery, which was destroyed in the 1983 Ash Wednesday bushfires and bought by the state government.

The Stirling Council opposed the plan, calling it “two black pyramids”.

That opposition grew, especially over potential damage to the surrounding environment and the project’s scale, and saw the plan scrapped and replaced with a $15 million bistro.

Similar ideas came up again in 2011 and 2017, but also failed.

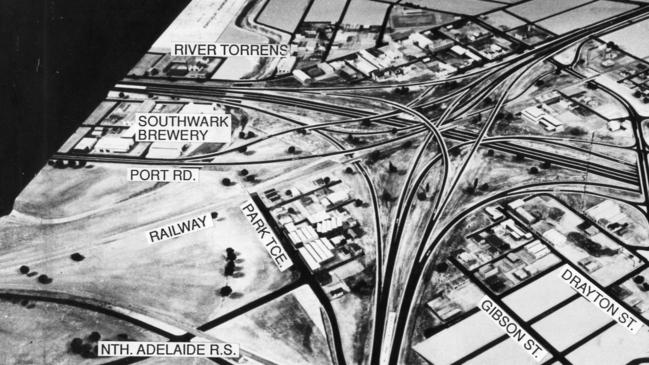

THE MATS PLAN

Every big idea needs a groovy acronym. In 1968 the Metropolitan Adelaide Transport Study (MATS) was to revolutionise Adelaide. There’d be a highway through Norwood and a subway under King William St.

The plan recommended freeways, an expressway, widening existing roads, new arterial roads, a new bridge over the Port River and upgrading train lines.

The cost was also staggering – $5.2 billion in today’s money.

It included a north-south freeway, referred to as the Noarlunga freeway, which was the centrepiece of the plan, a Port freeway, Hindmarsh interchange with connector to a Modbury Freeway, an eastern freeway connecting the under-construction South-Eastern Freeway to the CBD that would have gone through St Peters and Norwood, and a foothills freeway.

A Dry Creek Expressway was also recommended, a Glenelg Expressway (in place of the tram line) and upgrading much of Main South Rd to an expressway to Reynella.

A huge number of properties needed to be bought and demolished – 3000 for the Noarlunga freeway, including 800 homes. Hilton wouldn’t exist, and neither would Hindmarsh, possibly replaced with four levels of interchanges.

The reaction was vicious. People didn’t think such a huge plan was necessary, there were fears about forced property buyouts, and many were worried about demolishing historic homes in the inner southeast.

No matter. Vast tracts of land were bought in preparation.

The good news; Surviving was the O-Bahn, which was built instead of the Modbury freeway and the Southern Expressway partly follows the original plan for the Noarlunga freeway.

NUCLEAR ENRICHMENT / POWER / WASTE

A project so large and visionary requires official statewide NIMBY input, and in 2016 the verdict was a resounding ‘not in my backyard’.

It was a huge idea that could deliver $100 billion to the state — but ultimately a Citizens’ Jury flatly rejected a nuclear waste dump in SA.

South Australians had been speculating about enriching the locally produced uranium into fuel for nuclear power stations. Worse, God forbid, others even wanted the state to take responsibility for SA-sourced global nuclear fuel after it was no longer usable. The state could be paid to store it safely, they hypothesised.

Ultimately of all the options, a Royal Commission only recommended building a nuclear waste storage repository to take other countries’ low- and medium-level waste.

Citing potential state revenues of $5 billion per year, it found up to 5000 jobs could be created during the peak of construction, and about 600 full-time jobs once the facility became operational.

Then-premier Jay Weatherill was the driving force behind the investigations but went cold on the idea when the Liberal Party withdrew bipartisan support.

After intense ill-informed debate, a Citizens’ Jury released a report overwhelmingly against the dump, citing a lack of trust in the state government’s ability to deliver on the project.

A week later, Mr Weatherill said he’d like to have a referendum on the issue, but it needed bipartisan support. Ironically nuclear submarines are now to be built in the Port River at Osborne, albeit with bolt-on reactors making the system a little safer.

MULTI-FUNCTION POLIS

Even in Adelaide, the Australian champion in failed projects, only one idea was head-and-shoulders more of a spectacular failure than the nuclear plan.

Among some older Australians, the name still stirs long-buried memories of heroic failure. First proposed in 1987 and eventually abandoned in 1997, the Multi-Function Polis — or MFP — was national news. It was supposed to be a small, super-hi-tech city built on a swamp at Gillman, led by Japanese investment.

The plans read like the background in a sci-fi movie script, including a 2km-high man-made mountain to launch spaceships.

The entire project resembled humankind’s attempt at a utopian metropolis. There was a focus on integrating research, art, leisure, tourism and computers. At one point it was planned that bricks for the MFP buildings would be made of reconstituted sewage, and the houses would recycle their own wastewater.

Good old-fashioned racism was one of the reasons the project fizzled out. There were fears of an Asian enclave.

By the time Gillman was chosen for the site from several across Australia, this negative coverage had led to several Japanese investors pulling out.

The federal government pulled out in 1996.

In 1997, then-premier John Olsen announced the dream was over for SA. All that was left were two test drill holes dubbed “two of the most expensive holes in history”.

Planners of the grand scheme had forgotten one thing they should have known. For the entire 10 years of planning for the project, just down the road was the vacant aforementioned Le Cornu site, a tiny project in comparison, that could never progress past the planning stages.

But the MFP failure wasn’t for nothing — the state government built Technology Park near Mawson Lakes instead. And that project only took 15 years to get off the ground.

ADELAIDE 500 – PERMANENT GRANDSTAND

The annual V8 race on the Adelaide street circuit attracted between 200,000 and 300,000 spectators every year, more than justifying, some argued, a permanent presence in the city.

But after an eight-year courtship the race was left at the altar when Adelaide couldn’t agree on a permanent grandstand at the racetrack site in Victoria Park.

The Marshall Liberal Government cancelled the event in late 2020, with the government and tourism arm SATC, saying the ongoing impact of Covid and declining interest in motorsport made the marquee event unviable.

The race returned in December 2022 thanks to the freshly elected Labor government, but will still feature the costly circus of erecting and tearing down the entire track infrastructure every year.

In 2007 the city had an opportunity to secure the event and future motorsport races with a permanent grandstand at Victoria Park, which was mainly used at the time only by people walking their dogs.

The grandstand became one of the most hotly debated improvements to the city since Rundle Mall was developed in the mid seventies, to the howls of many opponents.

Needless to say, being a big-picture Adelaide idea, the grandstand never became permanent. Fortunately the main permanent grandstand enthusiast, then-treasurer Kevin Foley, channelled his inner big-picture thinking and was able to overcome Adelaide opposition to his wildly successful Adelaide Oval redevelopment in 2014 to bring AFL back to the CBD.

CROWS MOVING TO THE NORTH PARKLANDS

With Darwin and Hobart begging for a team in the AFL, along with the money and excitement that would flow from such a move, what CBD in Australia wouldn’t want one headquartered nearby right?

Like the Adelaide Oval itself, an AFL team in the city could be expected to bring colour, excitement, jobs, a tourism drawcard and all for little cost to the taxpayers.

The Power would have to be removed from Alberton with dynamite and anyway have their own redevelopment going on. But the Crows actually offered to set up near the city.

The Crows would have taken over the Adelaide Aquatic Centre which is now set to be closed for more than a year as it undergoes a $135m redevelopment.

SHIP BREAKING AT STONEY POINT

Premiers are used to oddball ideas coming over their desk, but an idea John Olsen was presented with in 1999 raised more than one eyebrow.

The audacious plan involved the massively polluting potential of running decommissioned ships ashore at Stoney Point, 35 km from Whyalla, breaking them up and recycling the metal components. An earlier plan for the project at Pelican Point had been flatly rejected.

Images of the developing world – where such schemes are viable because of slave labour and relaxed environmental laws – came to mind in the Premier’s office.

In one government briefing, not only was the scheme pilloried, so was its chief proponent after meeting with departmental staff. With a prominent hole in his shoes above each big toe, and a dishevelled brown suit, the would-be break-up expert was described in a briefing note to the Premier by one exasperated official as having “the demeanour and appearance of a homeless person”.

THE FLOATING HOTEL AT GLENELG

Way back before he became premier in 2018, Steven Marshall had a big boat to float at Glenelg.

The “exciting development” was a rejuvenated Glenelg jetty with a twist.

Mr Marshall wanted the taxpayer to fork out $20m to develop a Holdfast Bay council idea for a floating hotel just off the jetty. It was another iconic building of sorts.

“I’m talking about something which would be iconic,’’ Mr Marshall said. “It is a great place and people want to visit it but the infrastructure is tired.”

To be fair, the project would have included the more sensible new jetty, and marine tourist centre and public open space. The private sector would have floated the hotel.

The thought bubble burst when he was in government and sank in Gulf St Vincent.

It may have saved someone a lot of money. One other memorable throwback to Adelaide’s fascination with things floating was the Palais de Danse on the Torrens. It floated in 1924 and was literally sunk by 1928.

THE WAVE GENERATOR THAT DIDN’T FLOAT

Everyone loves renewable energy right? Almost zero environmental impact?

Tell that to the good folk of Carrickalinga who were subjected to a decaying failed wave generator experiment that was to power the state’s future.

For years the 3000-tonne, $7m white elephant stained the sea views from the town.

The massive metal machine was being towed from Port Adelaide to Port McDonnell in the southeast when things went amiss.

The broken-down eyesore was meant to be in the area for only a year from 2014, but work to remove it began in March 2021.

Only fishing sea birds and barnacles will mourn its passing.