John ‘The Beast’ Zisimou: The inspiring and tragic story of an SA music scene Goliath

HIS name was John Zisimou but they called him John the Beast, a huge human with a heart of gold. His band was called Escape and, in the 1980s, they were on cusp of becoming giants.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Metal and J-pop singer/pro wrestler Ladybeard returns to Adelaide

- Triple M blasted over Hottest 100 rip off

- The worst albums of 2017

- Punk icons The Saints immortalised

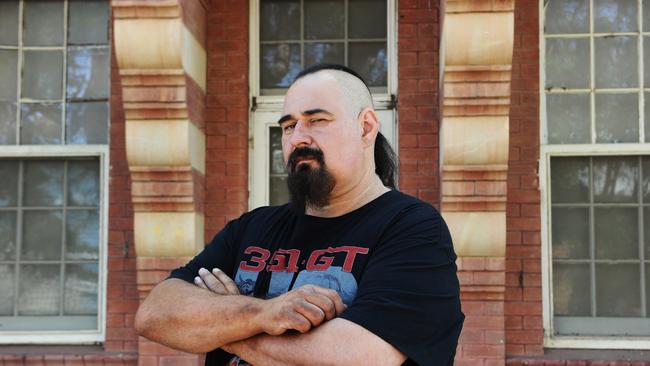

HIS name was John Zisimou but they called him John the Beast, a huge human with a heart of gold.

His band was called Escape and, for a couple of years in the 1980s, they were on cusp of becoming giants of the music scene. From Ray Martin’s Midday Show to the ABC’s Beatbox, you couldn’t escape from Escape.

Their tight metal sound and, perhaps just as importantly, their outrageous look saw the band on the front pages of newspapers and featuring in magazines. It even landed them a cameo role in a feature film.

But a broken leg and a broken heart saw John the Beast’s heavy metal dream slowly fade and, after a long battle with poor health and alcohol addiction, he died on November 27.

For Tony Zisimou – brother and bandmate – it’s a tragic tale but it’s also a tale filled with laughter, joy and the brash hopes of a bunch of kids from Gawler who were determined to be the best in the business.

“It’s a bloody rock’n’roll car crash,” Tony says over a quiet beer in the front bar of the Mawson Lakes Hotel.

“I knew the story had to end but I didn’t think it would end like this.

“Everyone knew him as John the Beast, John the loveable guy, John the rock star. I knew him as John Zisimou, John the best friend, John the f--ing arsehole.

“Sometimes we fought – that’s what brothers do – but, at the end of the day, we loved each other to death.”

The Zisimou story, in Australia at least, starts with Hristos, a bloke from a little island in Greece who dreamt of a better life in a country that hadn’t been ravaged by war.

AFTER settling in Adelaide in 1955, he fell in love with a girl from Yorke Peninsula named Mavis and, after several attempts, finally persuaded her to go out with him. They married and bought a rambling old convent in Gawler where they raised three boys – John, Tony and Chris – as well as a host of foster children from broken homes. “Mum and Dad were really caring people, and we had a happy childhood,” Tony says.

“It was a very family-oriented upbringing and Mum helped a lot of damaged people from bad upbringings. She really turned those lives around.”

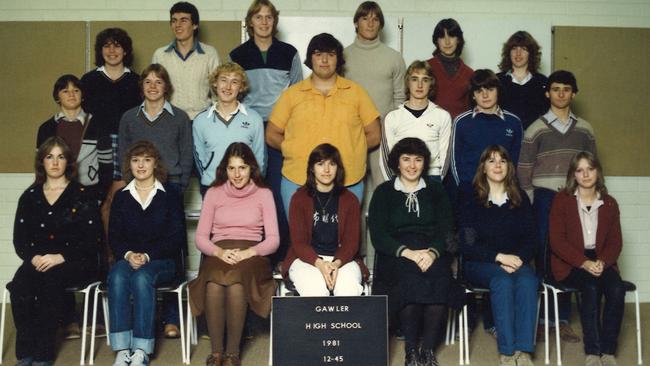

While life at home might have been happy for the Zisimou boys, it wasn’t so rosy down the road at Gawler Primary. Big boys with bad hair, John and Tony were easy targets for older bullies – but they gave as good as they got.

“We were the dopey kids at school, you know,” Tony says. “We were the kids with the bad haircuts and the homemade shirts because our parents were poor. We were the out-of-place kids. Man, we were fighting everyone. We’d be at primary school and the Year 7s would beat up on me and John, but we used to give it back to them.”

By high school, however, John’s classmates managed to look past his size and hair and discovered an intelligent young man with a wicked sense of humour.

“He started to turn things around and actually become very popular,” Tony recalls. “He was a natural entertainer. He had that pizazz.”

It was this desire to entertain that led to kernel of an idea that would eventually become Escape.

Taking on some work as a bouncer at the Gawler Mill Hotel while he studied nursing, 19-year-old John found out that the pub’s glass collector, Wayne Harrison, was a drummer.

They hatched a plan to form a band and become famous. The fact that John could barely play the guitar was nothing but an inconvenience.

“I thought, ‘A band! I want to be a part of this’,” Tony recalls. “I thought I could maybe play the bass. Well, I couldn’t and John could hardly play, either. The drummer was amazing, though!”

Realising that John didn’t have the skills to play the blistering solos that they needed in their newly-formed band, they recruited Michael Dryden as a lead guitarist. It wasn’t long before they admitted that they’d probably need a singer, too – “We didn’t really want to recruit too many people because it would cut into our millions”, Tony laughs – and Rob Gillett was brought on board. After discussing a laundry list of names, including Dextrostix (small strips used to test urine), the band settled on Escape.

“We did a survey at the Gawler Mill, wrote down a heap of band names,” Tony says. “There was a chick there called Trish who had a T-shirt with Escape written on it and she had amazing boobs. We were like, ‘that looks good’, so Escape it was.”

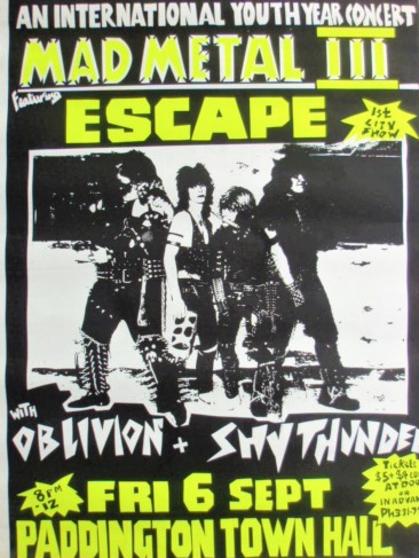

Full of bravado, Escape started drawing up their blueprint for world domination. Step one was landing a support gig with respected Adelaide metal act Almost Human.

“We thought, ‘this is it!’,” Tony says. “There was just one problem. We f---ing sucked. Every time we played a song another person would walk out of the room. By the time we’d finished playing the whole place was empty.”

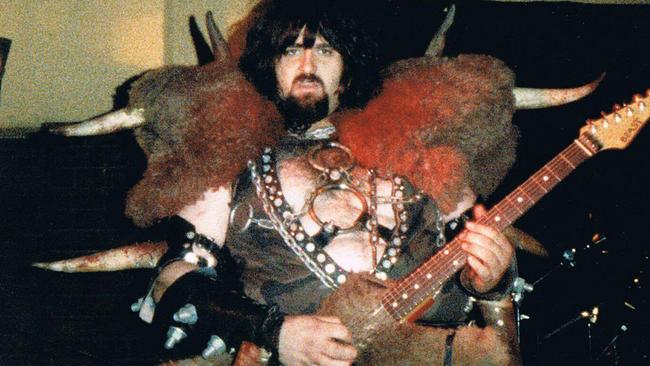

HUMILIATED, Escape took a year off and concentrated on learning their instruments and honing their craft. They also honed their look, covering themselves in leather, nuts and bolts – whatever they could find to enhance their Spinal Tap-meets-Conan the Barbarian image.

John, in particular, embraced the theatrics of heavy metal, transforming himself with leather, fur, studs, animal horns and a modified guitar with bolted-on engine extractors that could fire smoke bombs.

“When John was walking tall he was about 6ft 4ins (1.9m),” Tony says.

“Everyone said he was 6ft 6ins (2m)”, but that was because we liked the whole 666 thing. You know, John the Beast, 6ft 6ins and 26 stone! Just to stir up a bit of controversy. We were all wearing about 50kg of gear but John’s stuff was heavier again. I think at one point his stage gear weight was 80kg, plus he had the engine guitar.

“The name Beast actually came from Dad. We were having a dress rehearsal and dad came home from work and he was just crying (in a thick Greek accent), ‘Oh my God! My son’s a f--ing animal, he’s a f--ing beast!’ John thought that was pretty funny.”

It wasn’t long before the rest of Australia started taking notice of this band with its incredible image. Despite not having a record out, Escape found themselves all over national TV, appearing on Sounds with Donnie Sutherland, The Midday Show with Ray Martin, Simon Townsend’s Wonder World, Beatbox and even Willesee.

But despite the immense publicity, a record deal never happened. According to Tony, this was due mainly to a less-than-honest promotions man who’d attached himself to the band.

“Until recently, I think we had the most publicity for an unsigned band in Australian history,” he says.

“We’d been approached by record labels but that had been kept from us by a promoter who was supposed to be helping us because he wanted in on the deal. It was only years later that we found that out. We knew record labels were interested in us but this promoter was keeping it from us. “One of the guys who looked after Rose Tattoo once said to us, ‘You guys are a novelty band, but you’re probably worth $3 million each and you probably have three years in you, so record your album, get it out and enjoy the rest of your life”.

FATE can be cruel, however, as Escape discovered. Travelling from Sydney to Melbourne in December 1986 after playing in Brisbane just two nights earlier, fatigue caught up with manager Mark “Spook” Winders, the driver of the band’s van. Falling asleep at the wheel, he overcorrected and the vehicle rolled twice before slamming into a tree and crumpling in the middle “just like a stepped-on Coke can”.

Everyone survived but John was badly injured, breaking his leg and fracturing a vertebrae. The band kicked on, appearing in schlock-horror film Rock and Roll Cowboys with Peter Phelps (John modifying his gear to fit over his plaster cast). In reality, though it was the beginning of the end for both Escape and John the Beast. He began using painkillers to cope with his injuries and it was the start of a spiral into addiction from which he never managed to escape. A short-lived marriage compounded his woes and he started drinking heavily.

“John was a lover not a fighter but at that stage he was jaded,” Tony says.

“He’d lost the band he loved, he’d lost the woman he loved. He had this injury he couldn’t shake. It was a downhill spiral. Basically, everyone started feuding and it all went to shit. We broke up just before we were due to record an album and go overseas. We never got back together.”

John found work as a bouncer on Hindley St, working the door at the big clubs of the day including Jules, the Newmarket Hotel, the Century Hotel and Le Rox. Clubbers remember him as a gentle giant, an old-school doorman who preferred words over brute strength and he was always up for a chat. Eventually, though, his injuries and his addictions saw him living on a pension and spending increasing amounts of time in nursing homes and hospitals. Tony says there were many times over the past decade when he prepared himself to say goodbye to his big brother, only to have him pull through despite pessimistic predictions from doctors.

“At one stage, he was drinking three bottles of vodka a day,” Tony says. “It was madness and we could all see it. We tried everything – interventions and whatever. Nothing worked. About a year before he died, I was up the river and our younger brother rang and said, ‘John’s dying, you’d better come down’.

“I drove down to say goodbye, tears streaming down my face, and the next morning he wakes up and says, ‘Oh, hi everyone’. But even then the doctors said he had a massive amount of brain damage, liver damage, kidney damage, lung damage. He was in a bad way.

“In the end, it was a blood infection that got him. His body was too tired to fight it off. He’d just turned 54.

“He kept that pipedream of getting the band back together right to the end. I always knew that we’d never get together and play, but I didn’t think it would end like this.”

ESCAPE’S manager Mark “Spook” Winders laughs as he remembers the night John the Beast caused a genuine traffic jam on George St in the heart of Sydney.

“I was in Sydney with John for a promo visit and the Spinal Tap movie had just come out,” he says. “So we went down to George St where the premier was screening with John in his complete Beast outfit. There he was with a meat cleaver and a hand grenade – you’d never get away with it these days. He literally stopped traffic! People couldn’t believe it.”

Winders hooked up with Escape over a mutual love of Kiss, and together they would watch videos of the US glam rockers back at the old Gawler convent where the Zisimou brothers lived. He hit the road with Escape, mainly as the manager but also as the driver as you had to be 25 years old to rent a Tarago.

“We went on a six-week Beast in the East tour, taking in the entire east coast,” he said. “We had such a good time. I remember gatecrashing a Countdown party at Molly Meldrum’s house where Molly sat on John’s lap. Another night we played a secret warm-up gig with Angry Anderson and Rose Tattoo, Blackie Lawless from WASP came to see us play. It was incredible.”

Winders was also front and centre when things went bad, behind the wheel of the van during the accident.

“I was driving at the time and that’s something that will always sit with me,” he says. “I often look back on all the twists of fate that put us in that spot at that time. We’d left the show late, I’d taken a wrong turn which put us behind schedule ... it makes you wonder.”

Despite the accident, Winders says he looks back fondly on his time with Escape and John the Beast.

“We were like brothers, and it was a complete whirlwind,” he says.

“We had the time of our lives.”

A documentary on the Escape story, titled The Great Unsigned, is currently being produced by Canberra-based filmmaker Michael Kraaz