Is Senator Cory Bernardi the most conservative man in South Australia?

WHAT makes Senator Cory Bernardi tick? How did he form his views? And what does he think of the people that don’t like him? Here’s a look at a man polarising the nation.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Bernardi to quit Libs, set up own conservative party

- Why Bernardi said Trump would be president

- Christensen: I won’t follow Bernardi out the door

- Latest Newspoll has dire news for Liberals

- Andrew Bolt: Bernardi set to quit Libs

THE following article first ran in The Advertiser in May, 2011.

----------------

CORY Bernardi was walking back home from the local oval with his family when a car screeched to a stop. He watched as the driver leapt out and grabbed a passer-by and started laying into him.

What would you do in this situation? A. Move on quickly and get the kids inside. B. Call the police. C Jump into the middle of the fight.

Bernardi chose option C. He grabbed the driver, who struggled and ran back to his car, where a small girl was strapped in the back seat. On the front seat was an open bottle of wine. As the man tried to start the car Bernardi reached for the keys in the ignition. The driver punched him and bit him and then the brawl spilt out into the middle of the street. Bernardi managed to hang on to the assailant long enough for the police to arrive, but was astute enough to disappear when an ABC camera crew turned up. It turned out the man was wanted by police on several warrants and he is now in jail. The moral of the story, according to Bernardi’s wife Sinead, is: “He does things where other people walk by.”

Or perhaps Bernardi just likes a fight. Since becoming a Senator in 2006 he has made a name for himself nationally with his strident views on climate change, banning burqas, Islam in general and foul-mouthed Scottish chefs on television. He has been branded an extremist. A racist. A religious bigot. A climate-change denier. He has received death threats. He is hated by some within his own party. He has carved out a niche as South Australia’s “Mr Right” even if he shies away from the label.

“I consider myself a conservative rather than right wing,” he says in his city office. It’s a claim that would be easier to swallow if the largest picture on his desk wasn’t one of former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, a woman who defined a particularly fierce brand of right-wing political theory. Bernardi loves Thatcher. He has written to her, read her books and the highest compliment Bernardi pays his wife Sinead or mother Jo is to compare them to the Iron Lady. He is happy to describe himself as an “ideological warrior” but denies he is an extremist, a racist or a bigot. He is pleased, however, to celebrate his climate-change scepticism.

“I don’t think I am even extreme in the political culture of the day,” he says. “I think I reflect what a great many people think. That might not be politically correct but based on the responses I get from ordinary Australians they are grateful that someone is prepared to do it.”

Then there is Bernardi’s sense of certainty. Perhaps it’s related to his height. At 195cm, he still has the bearing of the world-class rower he was more than 20 years ago. He can withstand the slings and arrows of his robust parliamentary life because he brims with self-confidence that teeters occasionally into the realm of arrogance. In shorthand terms, he’s right, everybody else is wrong. “If there is an opportunity to do something and you have to absorb a bit of punishment along the way, that’s OK,” he says. “As long as I know I am doing the right thing.”

He takes comfort from his conservative heroes. Thatcher is on his desk and the speeches of the late US president Ronald Reagan are on his iPod. “Reagan was abused and mocked and derided by his own people for a very long time. It doesn’t mean he was right all the time but he put up with it and did what he thought was the right thing,” the 41-year-old says. To compare yourself to Reagan — even obliquely — requires a particular mindset. Sinead, who met her husband when they worked together in a pub he owned in the mid-1990s, says he doesn’t want for confidence. “Cory and I always joke we have a wonderful life, lovely family and lovely friendship and things go beautifully because we are both in love with the same man,” she says.

Bernardi has led an eclectic life. In conversation with him it’s apparent he is more than a one-dimensional right-wing ideologue. He has a sense of humour and is perfectly capable of making a joke at his own expense. He loves his family, is happy to listen to alternative views and has a broad range of experience. The son of an Italian immigrant who became a successful local businessman running hotels and liquor stores, Bernardi has rowed for Australia at a world championship, erected tents for Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, been close to death twice, twice sailed in the Sydney-to-Hobart yacht race and played an extra in a Cameron Daddo film. The Daddo film was particularly shameful because it required him to cast aside a longstanding hatred and join a union, even if only for a week. He also had a part-share in a pub in King William St and worked for a decade in the financial services industry.

Bernardi says his political views always strayed towards the conservative. Even during his school days at the expensive and exclusive Prince Alfred College he would write essays in praise of Reagan. He says his views were instinctive rather than considered but an early encounter with then prime minister Bob Hawke hardened his convictions. Hawke was taking questions on radio station SAFM and the 15-year-old Bernardi made the cut and asked him why more young folk were not involved in politics. He remembers a “polite, but bland” answer and that was that. Two days later a telegram arrived from the prime minister’s office apologising because Bernardi had not been able to ask his question. The next day the same telegram arrived again. He remembers both cost $6. “That compounded my view of an outrageous waste of taxpayers’ money,” he says. “I remember that and kind of thinking if these people are wasting this kind of money maybe I am the other type.”

After he left school he joined the Liberal Party at the invitation of Christopher Pyne. The pair grew up in the same Burnside street and were friendly — a fact which neither is keen to play up now as the relationship has deteriorated into barely concealed loathing. Thing were not helped when Bernardi wrote a column saying he had once played a round of golf with a politician who told him the only reason he ran as a Liberal was because he grew up in a Liberal seat. It was widely assumed to be Pyne, although Bernardi refuses to confirm or deny who it was. Pyne denies it was him.

But it was rowing rather than politics that was Bernardi’s first love when he left school. He won a scholarship to the Australian Institute of Sport at 18 and moved to Canberra. His friend Peter Murphy, who would go on to row at two Olympics, remembers a young guy with a lot of presence in a tough environment. Rowing on Lake Burley Griffin in the middle of a Canberra winter takes a degree of determination. It was all early mornings, hard work and regular escapes to the pub when schedules allowed. Murphy believes the discipline learned at the AIS has held Bernardi in good stead. “If it is ingrained in you for so long you don’t lose that determination and fight and desire,” he says. “Those skills as an athlete have transferred into his professional life.”

Bernardi rowed at the World Championships in Yugoslavia in 1989 in the coxless fours. But it was to be his last involvement at that level. A back injury forced him out of the boat and killed the dream of going to the Olympics. He won’t admit to regret that he never made the Olympics, but it’s clear it’s something he would love to have done. “But had I done that who knows what path my life would have taken,” he muses. “I wouldn’t have experienced a whole range of other things.” And in one of those flashes of self-deprecating humour he says retiring from rowing was good for the nation. The coxless fours team had to be restructured after he left, paving the way for a new breed to take over. What was to become the Oarsome Foursome was born, a team that would win gold medals at the Barcelona and Atlanta Olympics. “My great contribution to Australian rowing was actually getting injured,” he says with a laugh.

The experience still marks him today. He is an early riser and often goes for a walk in the pre-dawn darkness. He still works hard at keeping fit.

After his rowing career was finished, on impulse, he headed overseas. For several years he worked as an itinerant — if well paid — construction worker for a German company which built marquees for events such as golf tournaments and conferences. It was a job which took him all over Europe and into North Africa, where he did indeed erect a tent for Gaddafi’s regime. His adventure ended at Doncaster racecourse in England when he was hit by a car while packing up at the end of the day. He was pinned between the car and the truck. “The ambulance officer who came to get us said, the last one of these we did we had to scrape their legs off,” Bernardi says.

He required knee surgery and had a few days in hospital. He knows he escaped lightly, but decided he needed to come home to Adelaide. “It’s quite a defining moment of mortality that makes you think there must be something more than just going to East Germany and drinking beer and living in dud hotels,” he says.

Back home, he bought a share in the family pub on King William St called Bernardi’s. He also threw himself into the Liberal Party and became an active member. In another defining event, he met Sinead, an Irish immigrant who had moved to Australia when she was 20, and who was already working at the pub when the Bernardis took over. “My father always said if you can run a pub you can do anything,” he says.

But his life was to change again. He had been feeling ill for a while but had been ignoring his mother’s advice to see a doctor. He had a bad cough, was losing weight and was tired. Eventually he gave in and went to see a doctor friend who diagnosed depression. Bernardi wasn’t buying that but the doctor suggested he should play more sport as a cure. A few weeks later, after coughing up blood on the football oval, he sought a second opinion. The diagnosis was tuberculosis — a bacterial infection of the lungs which is rare in Australia, but can be fatal. He thinks he probably picked it up in Libya while building the Colonel’s tent. It is also contagious, and Bernardi spent the next four months in isolation wards at the Queen Elizabeth and Royal Adelaide hospitals.

In all he spent a year in isolation, including time at home, and was taking up to 50 pills a day at some stages to fight the disease. It could easily have killed him. He made some decisions in that time. The first was that he wanted to marry Sinead. The second was an extension of his vow to become more involved in community activism after the car crash in England.

“I thought there was something that I am meant to be doing that I am not doing,” he remembers. “I knew it wasn’t about money, I knew it was something about making a difference. It sounds trite but I thought it had changed my life and my direction in my life.” So he left the pub — the cigarette smoke would have been even more hazardous for his damaged lungs — married Sinead and ran for his first political office and became a vice president and then president of the Liberal Party. He became a stockbroker and started his own business. He saw the boom and bust of the financial cycle and in tones which have become familiar in his spiels against climate change laments the sheep mentality of many in the market. “You realise people will suspend their common sense,” he says. “They know nothing about XYZ mining but they have to get into it because their mates have.”

At the same time Bernardi was positioning himself for a run at parliament. He missed out on preselection for the seat of Hindmarsh at the 2004 election but won the ballot when it was time to select a replacement for the outgoing Robert Hill. It was a victory that upset the more moderate elements of the party.

His maiden speech gave the first hint of where his political values lay to a wider audience. It referenced family, marriage, small business and the economy and ended with: “I shall be guided by my conscience, my family, my country and my God”. Today his definition of his conservative political philosophy runs along these lines: “I call myself a conservative because I want to conserve a lot of the economic and cultural benefits that have accrued over the course of generations.”

This is the basis for Bernardi’s subsequent career. He came to national prominence as the driving force behind a Senate inquiry into swearing on television after being appalled by the f-words and c-words liberally thrown around by chef Gordon Ramsay. He has taken high-profile stands against gay marriage, multiculturalism, Islam, banning the burqa and climate change.

His enemies paint him as an extremist. His friends think he is the victim of left-wing media who don’t agree with his world view.

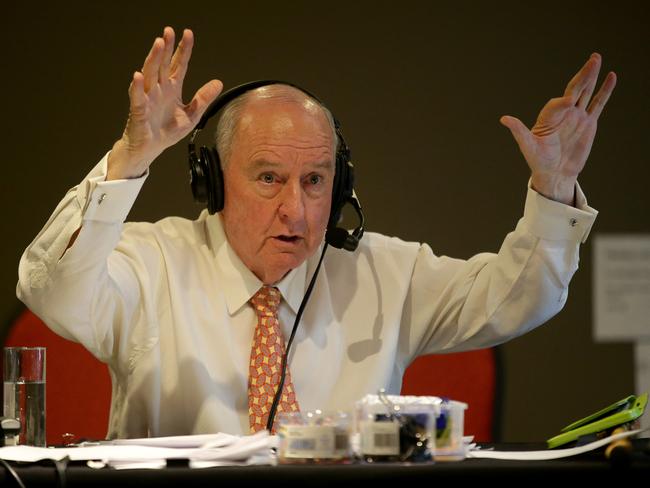

One of his supporters is the enormously powerful Sydney talk-show host Alan Jones. Jones and Bernardi served together on the board of the Australian Sports Commission and remain friends. Jones believes Bernardi’s views are representative of mainstream Australia. “If someone in the media, and there is a stack of them on the left, disagree with the views of another the easiest way to dismantle those views, they think, is to brand them with certain labels,” he says. “Howard’s had it, Abbott’s had it, Cory Bernardi, he’s in pretty good company, he is no way an extremist.”

Another of Bernardi’s mentors and protectors is the former Howard Cabinet minister Nick Minchin who leaves the Senate on June 30. Like Jones, Minchin believes a media dominated by left-wingers is happy to pin unfair labels on Bernardi. “The ABC and Fairfax in particular are bastions of left-wing views in the Australian media,” he says. “Almost unconsciously therefore Liberal and national politicians of a conservative disposition tend to attract the hostility of that gallery.”

None of which explains why he generates such loathing in parts of the Liberal Party. Last month former Howard cabinet minister Amanda Vanstone wrote a column in The Age urging Opposition Leader Tony Abbott not to move the party too far right because it risks alienating middle Australia. Vanstone, seen as a moderate in the Liberal Party, singled out Bernardi as a particular problem and said he should have been sacked as Abbott’s parliamentary secretary for his “inflammatory anti-Muslim remarks”. Other opponents within the party are scathing but wanted to remain anonymous. “Australians don’t like extremists,” says one. “He is now perceived to be a racist and that is unfortunate for him.”

It’s a label Bernardi firmly rejects. “It’s not even a rational discussion,” he says. “How can you be called a racist for talking about another religion? It just does not make sense. What race can you please tell me is Islam? It’s not a race, it’s a cultural identity.”

But it is a dangerous game he is playing, as the death threats prove. He insists that Islam itself is not the problem, despite a recent clumsy interview where he said it was. Rather, he says, Islamic extremism is the problem and ponders why the more moderate adherents of the religion are not more forceful in the debate about its future. It all links in with his big preoccupation about social cohesion in Australia. It’s a topic he will explore more fully in a new book to be released in June called The Conservative Revolution. Bernardi believes the institutions Australia has been built upon are under threat. Whether it’s the family, the church or small business, he sees radical forces out to undermine them.

If it all sounds a bit far-fetched he points to the social problems experienced by countries such as England and France as evidence of what can happen when minority groups maintain their own distinctive cultures rather than adapting to their new surrounds. He also warns this tolerance of difference in Western democracies inevitably sparks a backlash. This is turn produces old-style fascist organisations such as the National Front in France, an organisation which he also abhors. But Bernardi believes the policy of multiculturalism in Australia is protecting “small pockets of extremism” and unless they are stamped out the nation will pay the price in the long term. “We have an opportunity to learn from the mistakes of other countries,” he says.

He is equally strident on the subject of climate change. Publicly and privately he advocated against then Liberal leader Malcolm Turnbull’s support for the Emissions Trading Scheme proposed by former prime minister Kevin Rudd. It was a battle he fought with Minchin and which ended when Abbott was elected leader and changed the policy. He says the ditching of support for the ETS and the election of Abbott saved the Liberals from a flogging in the 2010 election.

Bernardi says he does not believe carbon dioxide is a direct threat to the climate. “If I believed all the alarmist nonsense we would be underwater and not be able to go outside by now,” he says. Furthermore, he does not believe the vast majority of scientists who conclude climate change is a threat, saying most are dependent on government funding and need to come up with the right results to keep getting paid. In essence, they are being bribed to say climate change is real. “You can get a scientist to say almost anything you like,” he says. “There are lots of scientists who were paid to say there was no relation between cigarettes and cancer.”

Bernardi clearly enjoys his job. He seems to derive a perverse pleasure in the fact he annoys so many people. He says he is hoping to run again for the Senate and serve until he is 50 before reassessing what’s next.

His family is also highly political. Sinead Bernardi, who shares an almost identical world view to the Senator and doubles as his principal adviser, once rang ABC talkback to spruik her husband’s efforts in Canberra. Sons Oscar and Harvey conduct polls at school to determine who the parents of their classmates will vote for. Sinead says Bernardi revels in the lifestyle. “Cory has this great way of dealing with things,” she says. He sails through stuff that would get ordinary people down and leave them in a heap. “They would need psychiatric help to get them out of it, but it doesn’t get him down”.

Despite the immense self-confidence, Bernardi has learned the value of caution.

As our interview ends he leans over to switch off the tape recorder that has been tracking our conversation. It’s not that he’s paranoid, it’s just when you have built the reputation that Bernardi has you become a little worried about being taken out of context. “I am not interested in contributing to my own hanging,” he says.