Incredible logistics of sending letters to soldiers in World War One

DURING the tumult of World War One, billions of letters, newspapers and care parcels crisscrossed the globe. The logistics of sorting and sending those letters and parcels was extraordinary.

IT was a feat of human ingenuity, a vast and meticulous operation to send billions of letters, newspapers and parcels back and forth across the globe during the tumult of World War 1.

The four-year conflict engulfed the world, unprecedented in its violence and toll upon humanity.

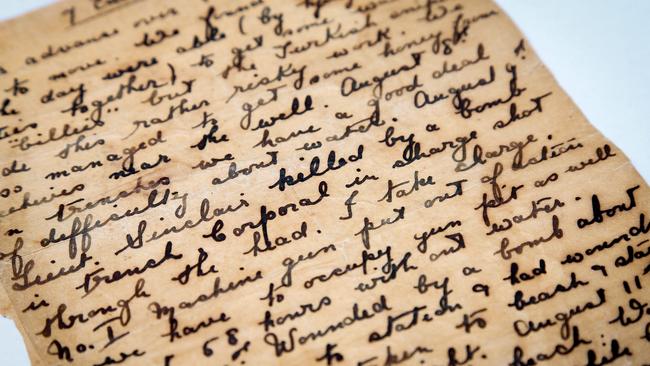

A century on, the letters provide a harrowing time capsule of the tales of battle from Australian men on the frontlines, and the anxious wait endured by families here and across the globe.

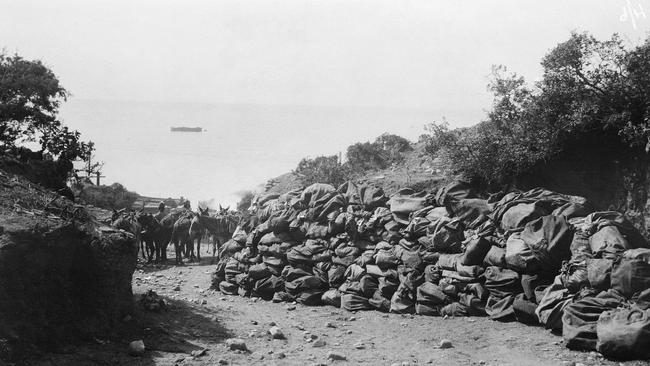

The logistics were staggering. Take the passage of a letter or care package from the Adelaide Hills to the Western Front.

From town or city Australia Post offices, letters were taken by rail or horse-drawn cart to the nearest port, on mail steamers, troop or transport ships to Liverpool in England. Trains took them to London’s Australian Base Post Office to be sorted, and once bagged and numbered, they went by van to Folkestone port, then across the channel to Boulogne in France. French dockers used the serial numbers to put them on rail trucks to go to train station nearest the destination.

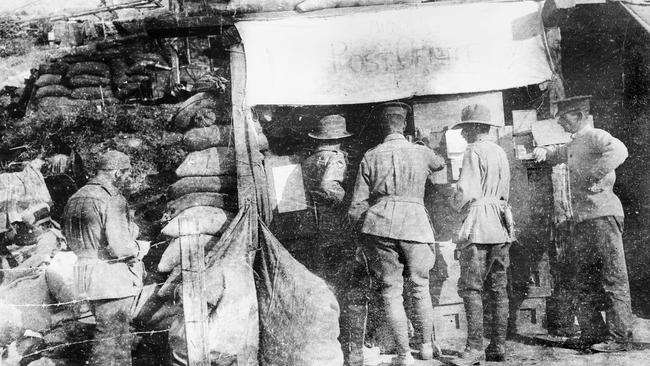

After another train journey, the bags were put into trucks or horse-drawn carts to the Field Post Offices, which could be anything from a wooden hut to a muddy dugout in the grim battlefields. From there, a horse-drawn cart took the cargo to Company HQ.

Finally, a rations party would find the men and deliver their only link to the world they once knew.

That would take between six and eight weeks. If it made it at all.

In line with the descending morass of bloodshed of the war, less and less parcels and letters made it through German snipers, submarines or myriad of other potential misfortunes.

Women bore much of the phenomenal load of compiling, sorting and sending the care packages, the exhausting task in the agonising knowledge there was a good chance it would end in enemy hands or simply be destroyed.

A bleak procession of days where the postie did not stop, followed by sleepless nights of uncertainty befell many families.

Like the parents of Roy Neville White, a clerk who played lacrosse for Holdfast Bay, who was 24 when he joined the war effort in October 1914.

Severely wounded in the landing at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915, he spent four months in hospital but returned to the battleground months later, then went on to France.

In 1916, Corporal White’s family was told he had been killed in action, and a report followed in the Adelaide Chronical newspaper.

But months later news surfaced that Cpl White had not been killed, and was interred in a German prisoner of war camp.

In response to Mrs White’s letters pleading for word if parcels were being delivered to her boy, the Prisoners Department secretary Miss Chomley wrote from London to her department equivalent in Adelaide during the final year of the war.

Official letters to civilians were by today’s standards curt, even callous, in their brevity.

But Miss Chomley’s typed letter to Mr Edmunds Esq is frank and revealing.

She conceded “in French territory behind the German lines … parcels are very seldom delivered and the conditions are generally very terrible”.

Urging discretion on what to pass on to families, she said Mr Edmunds should know the truth “in order to defend the Australian Red Cross against any undue criticism”.

“It is difficult for people in Australia to know what war conditions really are, and it is kinder to the relatives, especially if they are anxious mothers or wives not to tell them too much.”

As the world grappled with the enormity of its grief combined with the elated relief of the November 11 Armistice, Mrs White received another letter from the Red Cross Information Bureau in early December.

Her son was alive. Sgt White had been found in a German prisoner of war camp where he was captive since 2016.

“Dear Madam … The above soldier has been exchanged to London arriving there on November 20th ‘quite well’,” the letter states.

“We are sincerely glad that your constant anxiety since your son has been a prisoner of war is now ended and hope that you may soon have him home again.”

Mrs White’s elation flowed through her cursive handwritten reply of December 14, 1918.

“I desire to thank you for the information … regarding my son’s arrival in London after having been a prisoner of war in Germany for over two years,” she wrote.

“Also thanking you for your kind congratulations on my son’s release. I am Yours Gratefully.”

The nightmare was over. But this was a cruel war with few happy endings.

On December 6, eight days before Mrs White had penned her heartfelt letter of thanks and relief, Cpl White had died of Pneumonia while on leave in the English village of Monkseaton.

He was 28, and was one of thousands of soldiers who survived the savage bloodshed of war only to be struck down by a Spanish flu pandemic which wiped out more than 50 million people worldwide.

Word of Clp White’s death did not filter back to South Australia until January.

His relieved parents would have rung in New Years of 1919 with a sense of optimism — but within days they would learn the son who had survived so much was never coming home.