‘I never had no voice’: Raymond Finn reflects on being taken and denied his culture as a young Aboriginal boy

Stolen Generations member Raymond Finn says he was hesitant about the Voice at first.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

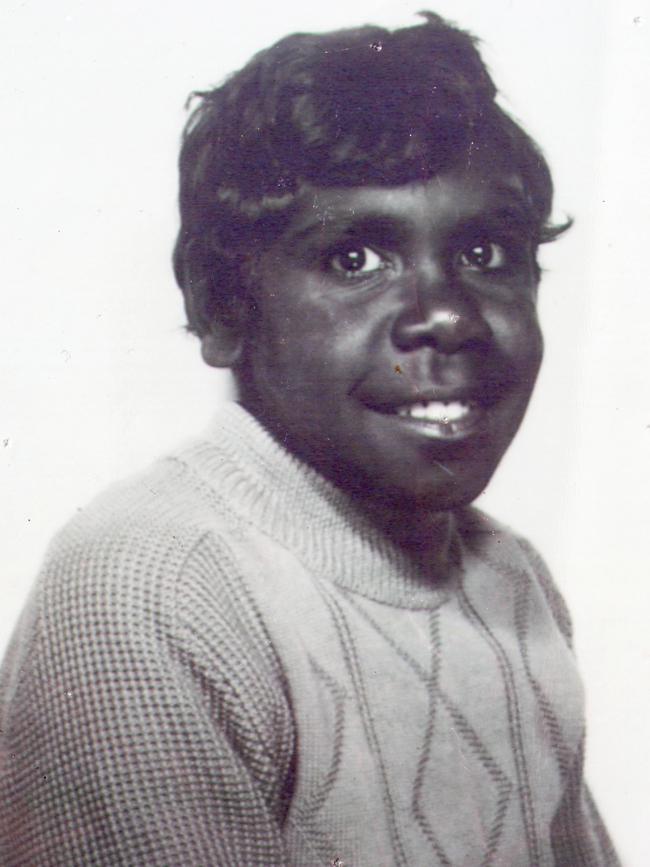

Forcibly removed as a six-year-old child from his family and country in remote northeast South Australia, Raymond Finn remembers how his voice and culture was taken from a young age.

“We were Aboriginal in spirit, but we had a white mentality that was flogged into us,” he told The Advertiser.

A Wangkangurru man whose family descends from the Simpson Desert region of SA, he was taken and placed in the Colebrook Children’s Training Home in the Adelaide suburb of Eden Hills.

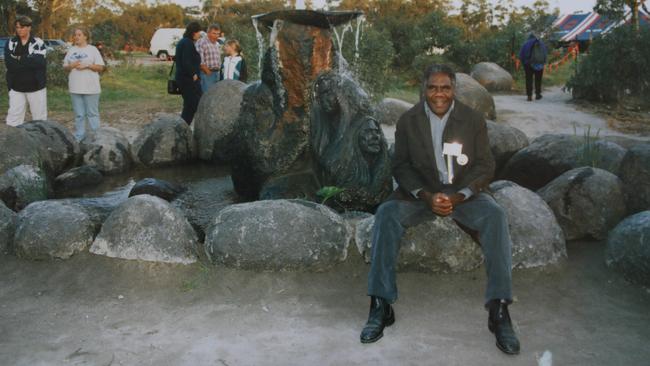

On Wednesday, he revisited the old site where he spent four years from 1969 to 1973.

“I was lost here. I didn’t know who I was, and that’s what they wanted to do. They wanted to dismantle that cultural element or that spirit that was in you,” he said.

“They were trying to suppress that and that’s what I felt here. They were suppressing my spirit and they wanted to make us like good white citizens.

“It’s sad because I was taken away and put in this little place here – out of sight, out of mind – and in a school where I didn’t know who I was.”

Mr Finn attended the local Blackwood Primary School and says he was the only Aboriginal student there when he went, which he said was a place that also denied him his culture.

“I was the only black kid there in that whole school,” he said.

“The principal and through the mission here, would say to the school and to the principal, ‘don’t say anything black, don’t say anything Aboriginal, because there was no Aboriginal education there.

“There was no story and I just had to get on with what they were teaching us and they didn’t teach black history at all.”

At 11 years-old, he eventually found his way back to his family and “worked” as a cook’s helper on Anna Creek Station, about 820 kilometres north of Adelaide.

However, he was not paid for his labour from 1973 to 1978 and says that he and his family “worked for nothing”.

“I was a child labourer at the age of 11 and didn’t get any payments,” he said.

“The white man didn’t want to pay me or my family any wages.

“The only time I got money was a handful of coins that were given to me and I was told to get on a train and piss off.”

Weighing in on the debate around the federal government’s referendum on constitutionally enshrining a First Nations Voice to Parliament, Mr Finn says he reflects on his childhood experience at Colebrook and working at Anna Creek Station.

Although, he admits he was reluctant to support the Voice at first.

“I was a little bit hesitant at the beginning because I just didn’t know,” he said.

“My journey on this at the moment is, this particular history and even coming here, has inspired me to look at this issue (the Voice),” he said.

“Because we were kept like mushrooms, out of sight, out of mind and now is the opportunity to make something of it, and when I look at this (the Voice), this is a human rights issue.

“I am thinking deeply on this because of the history and the human rights abuses on a world scale.”

During the fifty-four years of its existence, Colebrook was ‘home’ to over 350 First Nations children, many who suffered at the hands of missionaries.

It was first established by the ‘United Aborigines Mission’ in 1927 at Quorn in the Flinders Ranges, but was moved to Eden Hills in 1943.

All the children who were taken to Colebrook came from diverse Aboriginal cultures spread across SA and other states and territories, with many of the children never seeing their parents or family again.

The site where the building housed all the children has now been demolished and it has been turned into the Colebrook Reconciliation Park which includes the ‘Fountain of Tears’ and the ‘Grieving Mother’ statues, as a memorial for the mothers of the children who were taken there.

Mr Finn says being taken to Colebrook and reflecting on his time there, he will vote yes in the upcoming referendum because he wants his children and grandchildren to have better opportunities than he did.

“I definitely would vote yes because of that, because it’s for my grannies and my children,” he said.

“They need a voice, and for me personally, I never had no voice here in Colebrook Home as a kid, and now I’m saying yes to give my kids an opportunity.

“The history has to be corrected big time.”

The old site is also often visited by students from many schools in Adelaide and other regions across SA, where volunteers give guided tours of the area and talk about the history of Colebrook.