How to save South Australia according to Rathjen

Shorter degrees, more students ... and lots of coffee. Vice-Chancellor Peter Rathjen wants Adelaide University to save South Australia — in an exclusive SA Weekend profile, he explains how.

- Adelaide University’s radical six-month degree plan

- Adelaide Uni, UniSA merger plans shelved

- We weren’t planning a takeover: Adelaide Uni

- Prizes, discounts, freebies: Check out the latest subscriber rewards

Peter Rathjen counts many things when he’s deciding whether the billion-dollar business he runs on North Tce is moving forward fast enough.

On his walks around the University of Adelaide’s campus, the Vice-Chancellor might note how many students are wearing sweaters with the university logo, or the number of people buying coffee in the student hub.

Odd? Not at all, he says. The hoodies signal pride – and that could translate into philanthropy to the university in future. And the coffee? “Simple,” he says.

“I want to know that our staff and students are spending more time in our social spaces, in each other’s company, because that’s where ideas come from.”

Rathjen believes a successful university needs a vibrant campus, and on this fine day it is. Students lounge on the spring grass and a lot of coffee is being consumed.

The V-C, a former Blackwood High student and University of Adelaide science graduate, probably spent a bit of time lounging himself after arriving for the first time aged 16. A bit, but not much – given what must have been a full card.

Rathjen excelled not only as a student but as a pianist, soccer player, and as a national champion in orienteering – a sport which combines cross country running with negotiating mystery routes for which competitors only get a map once the race starts.

Orienteering requires stamina (now 55, he still runs 10-12km several times a week), speed and the ability to instantly plot a route to success – handy skills given the challenges universities face.

But if he is still quick on his feet, that’s nothing to the way he talks.

As we tour the campus, he rattles off ideas, plans, and history at a rate hard to keep up with. Here’s the new uni bar, over there boffins invented the world’s most accurate clock, down that way – indicating an opening to Frome Rd and the Adelaide Botanic Garden – is where the old university gates will soon be moved.

Yet alongside coffee cups, there are other numbers on Rathjen’s mind as he heads towards two years in the job in January.

One is the size of the student body at Australia’s third-oldest university, founded in 1874. At about 28,000 it’s too small – even with the surge in foreign students, now a third of the total – for his ambitions. Another is his budget. While $1 billion sounds a lot, when you’re competing with the likes of the University of Melbourne at around $3 billion, it’s not enough.

Then there’s the Top 100 lists which decide the world’s best universities. Adelaide sits outside the most elite band, but breaking into it would open new opportunities.

There’s another number too that worries him – 26, which is the percentage of South Australians aged 25-64 who have a degree, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

In a world where there are fewer and fewer unskilled jobs, tertiary education is vital, says Rathjen, and that number needs to be 50 per cent or more.

“Whatever semi-skilled jobs have been lost, more are going to be lost as we go forward,” he says. “We either help people to get into education, or we accept we’re going to have to pay welfare.”

That sounds grim, but Rathjen has a plan. He calls it “future making”, and says with innovation, new industries and global connections the university can help rescue SA.

Rathjen was born into the university world.

His father Tony came from German stock who settled on a Birdwood farm in 1840 (the Rathjens still have it) and was the first in the family to go to university. Rathjen Sr became a top wheat scientist and won a scholarship early in his career to travel with wife Cynthia to study at Cambridge University in England.

“They had very little money and the last thing they wanted was a child,” says Rathjen. “But they got me.”

The family returned to Adelaide in 1965, and his father worked at the Waite Institute for the next 50 years. Cynthia was a top linguist and taught German language and culture (she had no German heritage at all) at the old SA Institute of Technology.

Young Rathjen was into sport.

He still plays soccer, and was captain at university, where he is chuffed to have been named in the best team of the past 25 years.

When the family took up bushwalking, he went on to orienteering. “It’s a heavily physical sport, an endurance running sport,” he says. “The best orienteers are getting on to being Olympic-class runners.”

At home, he was never under pressure to excel academically. Nor did he have a particular job in mind at school. “I’ve never really had career aspirations,” he says. “I’ve always just followed short-term interest.”

At 16, he went to the University of Adelaide, where he quickly found he loved biology and geology. But when he tried to do both he was told it was a silly combination, made impossible by timetable conflicts.

“So I chose, and went down the biochemistry route,” he says.

“But two observations: one I’m still a frustrated geologist – I love geology and, in particular, palaeontology; number two, it would not have been a silly choice at all. It would have been very sensible given where research is going. And it taught me a great deal about curriculum flexibility and never imposing your view on what a student should be studying because sometimes they know what the future is better than you.”

He excelled in biochemistry.

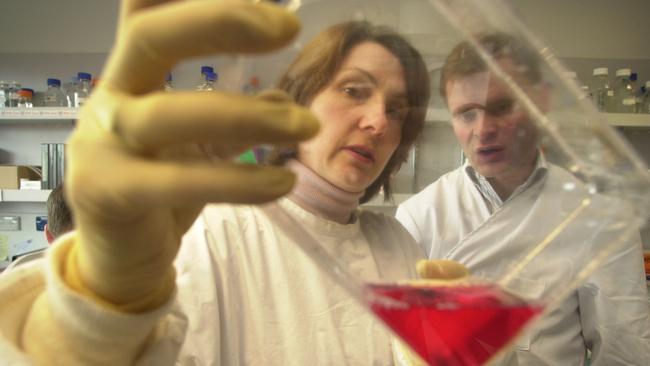

Early on, he was part of research which paved the way for others to create the then groundbreaking gene shears, a genetic engineering technology.

“I think it might have been the most important work I did,” he says of the research which was later commercialised by the CSIRO. He went on to research embryonic stem cells, those yet to differentiate into specific cells, such as hair or bone.

Rathjen also played piano, sometimes at Elder Hall, and studied part-time at the Conservatorium. He and a fellow student would play piano concertos for fun, one taking the orchestral role and the other the keyboard part.

Favourite composer? “Beethoven. Perhaps it’s the German heritage.”

The mix of sport and academic achievements helped Rathjen win a Rhodes scholarship in 1986, which took him to Oxford to do his PhD.

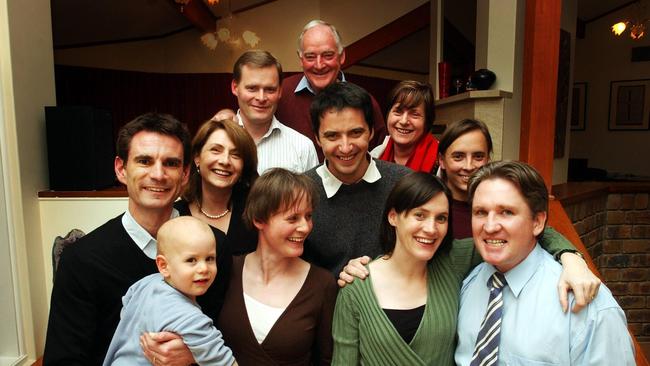

By then he’d also found time to date his future wife Joy, whom he met studying genetics and biochemistry at Adelaide (they needed special permission to marry in 1987, as Rhodes Scholars were supposed to be single).

Joy, now an Associate Professor and Scientific Director of the Basil Hetzel Institute, also completed a PhD at Oxford, a year after he did.

While his wife finished her studies, Rathjen drifted into stem cell research, but when he was offered a teaching job at Adelaide, he took it.

Back home, he kept up his research, often co-authoring papers with Joy. They didn’t always agree though, and their children Sarah, now 29, and Michael, 27, banned scientific arguments at home.

Rathjen was a rising star.

He moved into administration, becoming a professor and department head at Adelaide, before heading to the University of Melbourne as its youngest dean in 2006.

Two years later he was deputy vice chancellor, running the country’s biggest university research portfolio. Then in 2011 he was made Vice Chancellor of the University of Tasmania. “I just had offers,” he says, insisting he had no real career plan.

“They became interesting.”

Those jobs prepared him for Adelaide, where he became V-C in January 2018, and, at last count, earned $1,052,500 for his troubles.

He said Melbourne showed how to pursue excellence, Tasmania the gamut of challenges. On one hand it had world-class university research into the Antarctic; on the other disadvantaged communities in the state’s northwest didn’t consider education or university a priority.

The lesson he took was that universities must pursue excellence but also access and equity. That’s different to their traditional role. “Over the last thousand years we’ve trained about 0.4 per cent of the population, but now we train between 40-50-60 per cent if you’re in Europe,” he says. The reason is that the economy has changed.

“The state is suffering at the moment,” he says. “We are the experts in this space and we have to explain to people why education and innovation are the future of this state.”

Rathjen is on a mission, but his manner is methodical and intellectual rather than gregarious. Trim and fit, we’ve asked to photograph him on one of his regular runs through the bush. The man on the move. Not a chance.

Instead, more comfortable in corporate suit and tie, he wants to sell his inclusive education message and be pictured with kids who have graduated from the Children’s University, set up to encourage students from all backgrounds to think of university as a natural progression. SA has some of the nation’s highest poverty levels, and many in those communities don’t consider university as something for them.

You need to get someone from a family to be the first, he says, and then the dam breaks.

According to academic Andrew Norton, of Melbourne’s Grattan Institute, about 39 per cent of 19 year olds in SA are in tertiary studies, compared with 45 per cent in Victoria and 43 per cent in NSW.

Rathjen thinks at least half SA’s adults should have a degree.

But a new federal funding model for universities pegs the number of students to levels set in 2017. Some increase is allowed but nothing like what was provided under Labor’s “demand-driven” system when universities could for most courses accept anyone who passed their entry standards.

Rathjen says that under the new model SA is capped at a much lower level of participation than NSW and Victoria.

“This is a real problem for South Australia,” he says.

“If we want productivity improvement, if we want people to get good jobs, we must have a population that is as well educated as anywhere else in Australia and the world. I think we’re going to have to make that case to the Federal Government – that we need to be able to raise participation to the same level as the rest of the country.”

Another obstacle to a smarter state, he says, is the ATAR system, which by emphasising the need for a high academic score discourages high school students from studying more difficult subjects such as science and maths. As a result, the university is now guaranteeing access to certain courses without the need for high ATAR scores. “The ATAR should never drive subject choice,” Rathjen says. “It should be determined by the interests of the child.” Rathjen also blames the way science is taught – too boring – for turning kids off.

“We misrepresent science,” he complains.

“We teach it as being about algorithms and logarithms and equations and facts, and in fact science is a story about creativity and beauty. It shouldn’t be taught as hard, austere, difficult to access; it should be taught as fascinating.”

But his focus goes beyond the young.

The university must also engage the broader population – and make money – by including older workers who don’t have the time or inclination to learn on the campus. More online courses make sense, he says, but also shorter skill-focused degrees.

The university needs to “find educational products that are shorter and more directly targeted to the interests of the students themselves”. Without diminishing the value of the three-year bachelors program, “there’s another cohort of people now who need to be able to get out there and find a meaningful job, and need access to what we’ve got, to help them to do that”.

So two year degrees? “That conversation is very live in the university at the moment and we’re even talking to TAFE about whether there might be a partnership there,” he says. “I’m not just talking about two year degrees; I think we’re going to have to go to much shorter degrees.”

In Tasmania, he introduced work-focused “hands on” associate degrees of two years duration in areas like applied business or agribusiness, which count towards a bachelor’s degree. But Rathjen appears to have even bigger ideas for Adelaide.

He says the university’s Australian Institute of Machine Learning, rated number three in the world, and the winemaking degree, rated number two in the world, show how shorter degrees could be offered.

“So we’re extremely good at artificial intelligence and machine learning. It’s going to disrupt just about everyone’s job over the next 10 to 20 years. We need one-week courses, six-month courses, things like that, [so] that people can come into the university and maintain the skills they need,” he says.

In such work and skills oriented courses, Rathjen insists the university is still teaching thought, creativity, and how to accumulate knowledge and apply it to problems – “we’re just doing it in tailored packages rather than the broader three year degree”.

But, unlike a normal bachelor’s degree, students would have to pay full fees for any new shorter degrees. That could make them less attractive. “At the moment they don’t qualify for federal money, but I think that’s a debate the country should be having,” Rathjen says. If universities are going to upskill the nation, the government should help with subsidies or deferred payments.

But while Rathjen thinks universities can save the state by making people smarter, driving new industries through research, and creating greater connections to the rest of the globe, he needs more money.

The university needs to be bigger, he says.

Yet does size really matter? Some of the world’s great universities like Oxford, Cambridge and Harvard are relatively small.

“The issue in Australia is very simple: more or less alone in the world, we don’t fund research properly,” he says, insisting scale matters in Australia.

“So if you get a research grant the institution needs to find about 50c in the dollar to match the costs of libraries and electricity, and those kinds of things. We do about $200m a year of research and we have to find $100m from elsewhere to make that possible. That’s not true anywhere else in the world.”

Universities haven’t been able to convince governments that they should be funded more generously, he says.

So how does Adelaide find that $100m? Not from domestic students, who he says pay for their courses. Nor from industry which provide little research money.

“The profitability generally comes from international students [fees] and that’s what makes the situation actually work in Australia,” he says.

In other words, our university system is bankrolled by foreigners. These students – largely from Asia, mostly from China – now make up 31 per cent of Adelaide’s total.

Rathjen needs more foreign students, and he thinks getting them would be easier if the university could make the Top 100 lists.

That’s because one way students make their choice about which foreign university to attend is through these rankings. They measure various qualities, from teaching to research – and the latter is a big factor that helps drive a university’s ranking higher.

It’s also expensive.

So while Rathjen wants Adelaide to be in the Top 100 lists, to get there he needs more money for research. That should bring more students, which brings more money – a virtuous circle. But overall, to achieve his vision, Rathjen wanted a much bigger university.

To compete with the likes of Melbourne, he wanted a merger with UniSA.

But after talks, UniSA said no. There were claims from well-placed sources the deal died because of disagreements over who would occupy which positions of power.

Not true, says one person with knowledge of the talks.

“The issue wasn’t power sharing; it was culture,” this person says. “UniSA was about enterprise, social justice, more liberal in its leanings; Adelaide was more traditional and private school. They were contradictory cultures.” There was also, he says, no clear advantage for UniSA to merge, since it had no ambitions to be in the Top 100.

But this insider agrees with Rathjen that it is important for SA to have a Top 100 university (with the Australian National University, the universities of Melbourne, Sydney, Queensland and NSW, and Monash in Melbourne) to show that the state is not slipping in relevance.

Yet the source argues amalgamation is not the way, and would have cost up to $1 billion and taken a decade to bed in.

Rathjen, “as a South Australian”, remains disappointed.

“I think it would be nice to have a genuinely world class and recognisably world-class university in the city.”

Despite the rejection, he says there’s no reason the discussion can’t resume. As for the $1 billion cost, he says that was the top number and would have included new buildings which will have to be built anyway.

So Adelaide will have to go it alone to make the Top 100. There are three main lists: Adelaide is 106 on QS (Quacquarelli Symonds); 120 with Times Higher Education; and between 100-150 (about 132) on ShanghaiRanking.

Does it make any difference?

“There are opportunities that open up if you are in the Top 100,” Rathjen says.

“There are whole countries where the government funding can only be used for partnership with other universities in the Top 100. Some of the South American countries, which might be natural partners of ours in wine or mining for example, sit in that category.

“You can do better and serve the community better. That’s real. It would be very good if this state has a debate whether it believes that to be the case – and, if it does, what it might do to make it possible.”

That looks like a hint that the Marshall Government should kick in. Rathjen points out that Queensland’s universities have had spectacular rises up the world rankings due to a deliberate government strategy. “Queensland invested very, very strongly in its universities over a long period of time. They turned universities that were not strong into international powerhouses.”

It makes sense, then, that Rathjen has worked to build links with both sides of state politics, hosting senior MPs to dinner at his home and at Parliament House.

“It’s really a matter of trying to get a long- term vision for the state and work out where education sits within that,” he says of this schmoozing.

“If we are going to have one it needs to be bipartisan because every time you chop and change in education you confuse things.

“But if I’m right – if universities sit at the heart of future socio-economic prosperity – then the politicians will come to understand that if we make the argument properly, and it won’t be that they feel obliged to do things, or pressured to fund us, it will, if correct, be the logical thing to happen.”

Rathjen approached both state Education Minister John Gardner and Labor’s education spokesperson Dr Susan Close, who jointly hosted the parliamentary function where Rathjen and his senior academics made the case that the future of the state and the university were intertwined.

Close and Gardner have both also been invited to dinner at Rathjen’s Unley Park home, and are impressed by his energy and ambition.

“He has a clear understanding that the attractiveness and performance of the university makes the state stronger,” Close says.

“I’ve not heard a V-C at Adelaide express that as clearly before. He’s made a big effort to keep communications open with both sides of politics.”

Gardner also acknowledges Rathjen’s efforts to connect: “It’s the only time I’ve been invited to a V-C’s home for dinner,” he says. He adds Rathjen’s efforts and “outward focus” at the university have won respect from government and business, which recognises the university’s success can help drive the state’s economy and future jobs.

But some worry the University of Adelaide will struggle.

“Adelaide’s in the Group of Eight, the biggest research university in SA – but it’s under pressure from the other states,” says one person high in the tertiary sector.

“It’s eighth in the Group of Eight and likely to be ninth or tenth.”

“Not true,” says Rathjen.

“If you look at that latest ranking [in the Times list], for the first time in a long time we’ve gone up to seven [past the University of Western Australia].”

David Lloyd, Vice Chancellor at UniSA, told a CEDA lunch recently he believes Adelaide will achieve its Top 100 ambition in a few years regardless of the failure of the merger. Rathjen doesn’t seem to share that optimism. “It gets pretty hard when you get up there … it becomes very tricky.”

With no extra government money, and no merger, Rathjen knows his only real source of budget growth is foreign students. Most come from China, which means that universities are now financially vulnerable to any change of policy in Beijing.

There are also worries that universities have lowered standards to ensure the students, even those with limited English, don’t fail so the cash cow keeps producing. Rathjen denies that, and adds there’s nothing he’s seen on campus to suggest inappropriate political activity by the Chinese.

Australia has the third highest number of international students in the world behind the UK and the US. So how many students should Adelaide aim for? It hasn’t been decided “but we see a significant increase,” he says. Last year there was a 27 per cent rise in foreign students, and next year the figure is likely to be 24 per cent growth.

Most Australian universities are aiming for half the student body to be from overseas.

Adelaide’s aim is for a student body closer to 40,000 than 50,000, he says, and it is diversifying to reduce reliance on China. The overseas students will make the city stronger, and the state more productive.

“I think universities will turn out to be the most valuable assets countries have over the next few decades in taking control of their own future,” he predicts. “If we don’t have a crack and try to change things – they will never change.”

More ideas, more innovation. Best keep counting those coffees, then.