Helen Oxenham’s lifelong quest to end domestic violence

Helen Oxenham’s earliest memories are of a childhood destroyed by a violent father. Eight decades later, her campaign against family abuse is far from forgotten.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Helen Oxenham’s earliest recollection of childhood was not the joy of opening presents on Christmas morning, nor was it her first trip to the zoo.

“I remember banging against my father’s knees with my fists trying to stop him from beating my mother.”

She was three years old — the second of six children born to working class parents living in a two-bedroom community house in Dublin, Ireland.

“The house was filled with cries of terror, neighbours must have heard us but nobody came to rescue us.”

Their father’s abuse was overlooked not only by neighbours but teachers, doctors, police and clergy too.

“I was so devastated — we needed help and everywhere we went we were getting knocked back — it was like being hit all over again.”

It’s what led Helen — later as a migrant wife and mother in Australia — to help set up one of Adelaide’s first women’s shelter at a time when domestic violence was an un-coined term and matrimonial heavy handedness behind closed doors was accepted.

Now aged 88, the great-grandmother and cancer survivor from Cumberland Park is again launching a crusade against domestic violence.

She’s working to establish South Australia’s first public memorial for the continuing loss of female life (69 women last year alone) from the hands of a partner or ex-partner.

“It was a terrible life really,” says Helen of her short childhood.

She ran away from home several times as a child and finally left at 14 to escape the beatings for good.

“The terror experienced then is hard to forget. It never leaves you. I can’t remember what I had for breakfast but I can never forget that stuff.”

The memory of injustice, of suffering in silence, of her mother being told to “bear her cross” as a wife, of the truth being covered up and of having no power in a patriarchal society fuelled Helen’s courage for change.

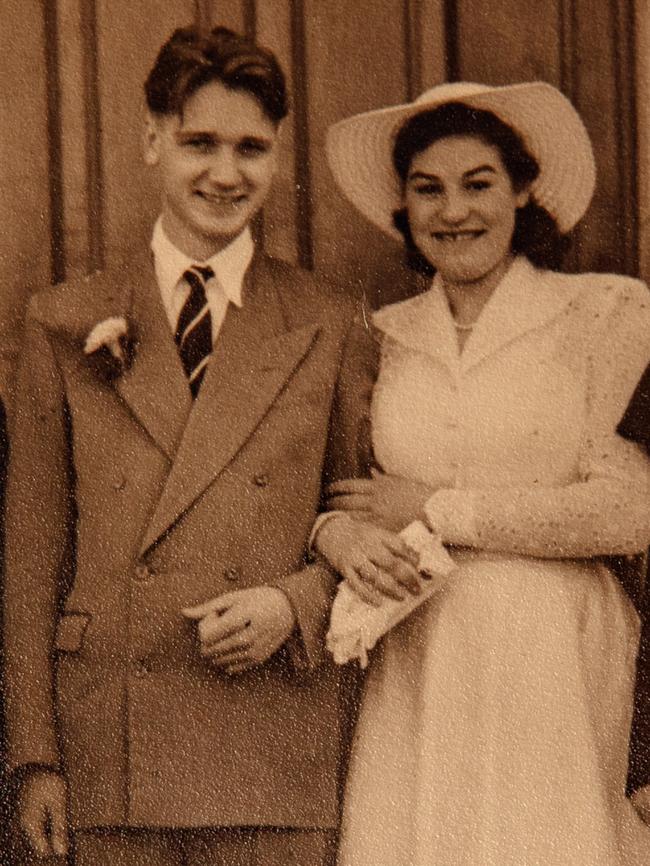

So in the early 1970s, in Christies Beach, Helen — then a 40-year-old housewife with three children — began a quiet revolution from the back of her husband’s watch repair store on Beach Rd. The couple married in Dublin and migrated to Australia in the 1950s with their first child.

Helen was studying Women’ Studies at Flinders University at the time and was frustrated by women’s lot in the world — unequal pay, unequal rights and continued marital abuse.

One day, a fellow student — Peggy Robinson, who was a secretary at the Department of Community Services — revealed there was a steady stream of bruised and battered housewives being turned away daily by the system.

“It broke my heart knowing that those women were being sent back to their homes,” Helen says. “I thought this only happened in Ireland and I had left it all behind. “It started a fire in me.”

Soon after, Helen and Peggy and two more women — both housewives with the same passion for equality, Josie Harvie and Connie Fraser — opened a drop-in centre for local women in the hope of inspiring reform.

It operated for a month from Monday to Saturday morning but soon the friends came to realise the women of the south needed much more than a chat over a cup of tea.

Night after night, Helen says, they would come — once the husbands were at the pub, or drunk in bed, with their children seeking refuge at the rear of the watch repair store.

The drop-in centre became too small. Helen, Peggy, Josie and Connie began approaching local and state government, doctors, churches and welfare workers to assist with the establishment of a larger shelter. They were met with great resistance — many believed that women’s shelters were just a guise for brothels and that domestic violence did not exist or if it did, it was the woman’s fault or a woman’s lie.

The four friends persisted and were eventually granted a Housing Trust home in Christies Beach.

Word of mouth spread, and local women rallied together to bake cakes and run social activities to help set up the new facility and keep the doors open. The community donated blankets, sheets and clothing, and the shelter got its furniture from the dump.

In February 1977, the four-bedroom shelter was opened and run by the four friends — all ordinary housewives — some holding down full time jobs at the same time while raising their own children and caring for their husbands.

They would clean each other’s homes while saving women’s and children’s lives — most of the time without pay. At maximum capacity, more than 20 women and children were housed at the shelter — leading to the set-up of a childcare centre and health centre in the 1980s.

The four friends were involved in the shelter up until the mid-1990s when it was taken over by a new custodian.

The shelter moved a number of times and has been absorbed as one of the southern suburbs’ domestic violence shelters still providing South Australian women refuge.

Helen — who has survived bowel, breast, and bladder cancer and persistent heart problems requiring aortic valve replacement surgery — has remained a strong advocate for women’s rights. She’s been involved in community housing for older women and an older women’s network.

Three years ago Helen was invited to address the annual general meeting of a southern suburbs shelter.

She was shocked to learn very little had changed.

“They still had not enough funding for these women and for the programs they needed and it was just like I was 40 years ago — nothing had changed,” she says.

“I’d thought once the shelters were there, the women would have the help they needed but it was all the same.

“I got so hurt — my heart was broken. I couldn’t sleep. It brought everything back again.

“All I wanted that night was to cry and be in someone’s arms and there was nowhere for me to go.

“I don’t want any more women to feel like that — to feel alone.”

Tired of Australia’s societal and political passivity over a rising domestic violence death toll, Helen’s now become the driving force behind establishing The Place of Courage.

It is a concept sculptural garden — SA’s first publicly dedicated memorial to domestic violence victims — planned for Mirnu Wirra Park (Park 21) in the South Adelaide Park Lands.

She says it will be a gathering place for victims of domestic violence to heal and gain courage. It will also serve as a public and permanent message that domestic violence kills and has ripple effects that lasts generations.

She’s gathered a small army of friends, survivors and women’s rights advocates now lobbying politicians, charities, women’s services, the general public and benefactors to help raise the money needed to make the memorial happen.

“South Australia was the first to give women the vote, now let’s be the first to end domestic violence.”

For more information visit: www.spiritofwoman.com.au

FOR SUPPORT PHONE THE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE CRISIS LINE ON 1800 800 098