Healthy benefits of nuclear thinking: A look inside Sydney’s Lucas Heights reactor

AS South Australia considers becoming more involved in the nuclear fuel cycle, Peter Jean visits Australia’s only nuclear reactor at Lucas Heights, Sydney.

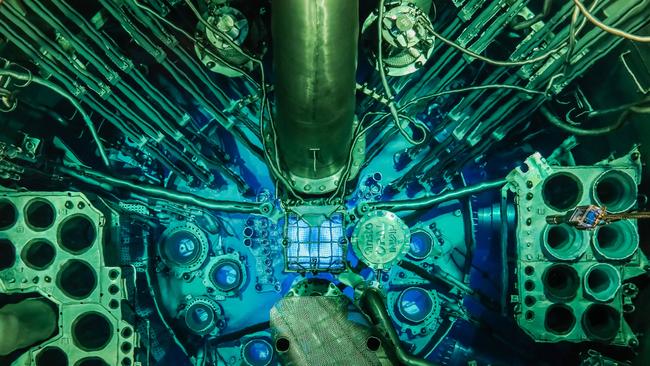

PEERING over the side of a 13m-deep pool at the submerged core of a nuclear reactor, my biggest worry is my glasses somehow slipping off my face and falling in.

We’ve been assured that dropping something into the pool won’t cause a meltdown. But the lost items wouldn’t be returned.

As a Royal Commission mulls the options for increasing South Australia’s involvement in the nuclear fuel cycle, many Australians are unaware the nation already has a nuclear reactor.

Some people wrongly assume that the Lucas Heights facility in Sydney is a nuclear power station supplying power to the grid.

Others are aware the reactor has a role in the creation of nuclear medicine but don’t know that Australia will soon be producing a quarter of the global supply of a vital cancer diagnosis drug.

Even more surprising is the range of scientific and industrial research being undertaken on-site using neutrons released by the reactor during the fission process.

The research ranges from imaging fossilised dinosaur embryos to assessing the strength of pipelines for the oil industry.

The publicly-owned Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation Lucas Heights facility is housed on a sprawling high-security campus, among in bushland in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire.

About 1200 staff (one third of whom have PhDs) work in buildings on streets with names such as “Einstein Avenue’’.

A sign at the on-site motel doesn’t contain directions to a fallout shelter but does warn asbestos may be present in the building and should not be disturbed.

The Open Pool Australian Light Reactor (OPAL) is housed in a concrete building covered in a cage designed to help the building survive an aircraft crash.

Close by is the now-defunct High Flux Australia Reactor (HIFAR), which opened in 1958.

Before entering the OPAL building, we visit staff working with material generated by the reactor

On the door to a building where nuclear medicines are prepared for dispatch to hospitals around Australia and overseas, a sign reads: “Australian made goods proudly sold here.’’

Half of the Australian population will benefit from nuclear medicine products created at Lucas Heights.

ANSTO executive Shaun Jenkinson, who has responsibility for business operations, is justifiably proud of the work staff do to prepare the product Technetium-99m.

The reactor is used to create the parent-product Molybdenum-99, which depletes into Technetium-99m.

The product can then be used in scans for cancer and heart diseases.

“The quality of these scans is getting better so they can see so much more,’’ Mr Jenkinson says.

“And good diagnosis means you save on treatment because you’re not giving people the stuff they don’t need.’’

About 10,000 doses of Technetium-99m are manufactured each week.

Some doses are flown by Qantas in containers lined with depleted uranium to the United States, China, Japan, Korea and South Africa.

The completion of a new production facility at Lucas Heights and the closure of an ageing Canadian reactor next year will see Australia’s share of the global technetium-99m market expand dramatically.

“At the moment we’re doing five to six per cent of global supply,’’ Mr Jenkinson says. “With our new facility – the upscale facility – that will take us to around 25 per cent of global supply, so we’ll be a major player.’’

Another regular piece of work for the reactor is irradiating silicon to create semi-conductors for advanced electronics.

“We get large silicon crystals, we put them in the reactor, dope them through with neutrons, which then get processed into wafers and used in high-end electronics, such as high-speed trains and hybrid cars,’’ Mr Jenkinson says.

“At ANSTO we have about 35 per cent of the supply for that – we’re the biggest in the world for doping silicon.’’

In a Bunning’s Warehouse-sized hall containing instruments with names such as “Wombat’’ and Echidna’’ researchers at the Bragg Institute use neutrons to conduct an array of research projects.

Bragg Institute scientific co-ordinator Joseph Bevitt explains that neutrons can penetrate objects far more deeply than X-rays.

“Neutrons pass through materials and as they pass through they interact with the materials,’’ he says. “That means you can use neutrons for imaging inside a material. So, you’ve got fossils inside the rocks you can see them.’’

Industrial research includes work on improving solar panels, assessing the strength of British-built oil pipelines that will be used in the Middle-East and even studying the properties of eye drops and solar panels

It’s time to visit OPAL itself.

Entering the reactor floor and other parts of the campus where radioactive material is handled requires donning gowns, gloves and bootees and wearing a personal radiation counter.

Watched through windows by control room staff, operators on a bridge use a hoist to lower items into and out of the core, which is about the size of bar fridge.

Operations manager David Vittorio says the open pool design makes OPAL user-friendly.

“Using water as a medium to move things around is very typical of a research rector and it makes it easier to load things in the reactor, irradiate them and then remove them from the reactor,’’ he says.

To create fission, a neutron hits the nucleus of a uranium atom and splits the atom, creating more neutrons.

The core contains 16 fuel assemblies, containing 21 uranium fuel plates.

The reactor can be shut down in less than a second using control rods or by draining water from the pool.

Spent fuel rods are moved to an adjoining pool.

The reactor is tiny compared to the plants used to generate electricity overseas.

It contains about 25kg of uranium, while a power reactor will have hundreds of tonnes of the fuel.

As we leave the reactor floor and take off safety gear, we are screened using two different devices to detect any radiation exposure.

Photographer Craig Greenhill’s cameras are given an especially thorough going-over by a safety officer and paperwork is prepared certifying that they are uncontaminated.

And like most visitors, we leave amazed by this little-known Australian scientific success story.