Has part of the mysterious Somerton Man code been cracked?

The mysterious code in a poetry book linked to a still-unidentified man found dead on Somerton Beach in 1948 may have referred in part to a British post-war aircraft.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The mysterious code in a poetry book linked to a still-unidentified man found dead on Somerton Beach in 1948 may have referred in part to a British post-war aircraft, according to a man who may have partially cracked the code.

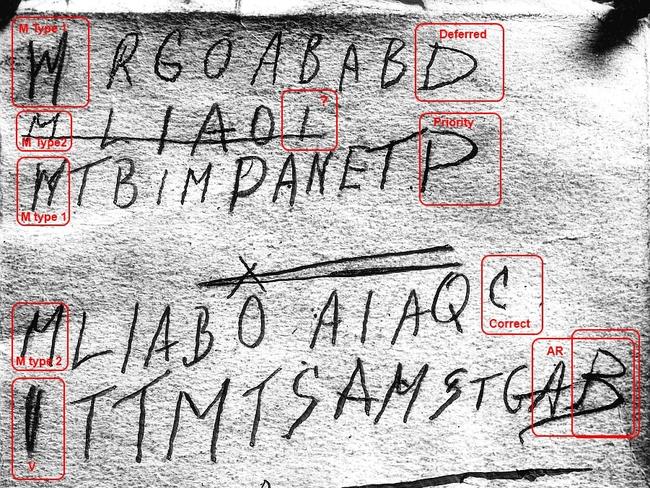

Former UK detective Gordon Cramer, a research member of the Association of Former Intelligence Officers, says parts of the code match with Morse code letters found in the World War II Radio Operators Manual.

Certain letters — or prosigns — were used to signify basic instructions to avoid using longer words.

And while the message of the code itself is still unbroken, Mr Cramer believes to have found an even deeper mystery — micro-writing hidden within the letters of the five lines of code.

He said a line of micro-writing appears to refer to the de Havilland Venom — a British post-war jet, which was still on the drawing board at the time.

The Somerton Man is one of South Australia’s most enduring mysteries and theories range from a man trying to visit his illegitimate son for the first time to a double agent murdered during the beginning of the Cold War.

He was found dead on Somerton Beach on December 1, 1948, slumped against a seawall. He was never identified and an autopsy said he died of unnatural causes, probably because of an unknown poison.

The death coincided with the start of the Cold War and, according to Mr Cramer, the visit to Adelaide of high-ranking British officials and weapons development at Woomera — the later site of nuclear testing.

A coronial inquest found a roll of paper hidden in a secret pocket in the man’s clothing.

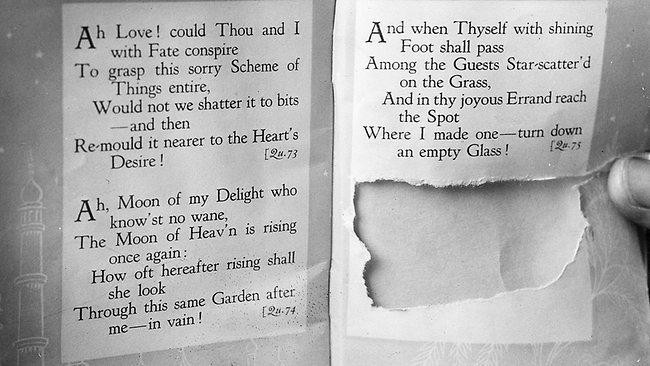

On it was printed Tamam Shud, or “finished” in Persian. It was torn from a book of Persian poetry — the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyáma . A Glenelg doctor found the book thrown through the open window of his car.

When the back page of the book was treated with iodine during a coronial inquest, five lines of code appeared — letters that have mystified police, code-breakers and amateur sleuths the world and internet over.

The phone number of a local nurse, Jo Thomson, was found in the book. Her home was five minutes’ walk from where he was found dead.

Ms Thomson identified the body as one Alf Boxall, to whom she said she had given a copy of the Rubáiyát.

But Alf Boxall came forward, alive and with his copy of the Rubáiyát intact.

Mr Cramer, who lived in Adelaide from 1977 until 1990 and now lives on the Sunshine Coast, said a line of the micro-writing appears to refer to a British post-war jet.

The micro-writing is mainly inside the larger letters.

“The larger letters then refer to what’s inside them,” he said.

“I estimate there are 1100 characters incorporated in the letters.”

One of the clearest spots is the large ‘P’ — or ‘D’ in the middle of the third line. Darker lines can be seen in the black of the lower half of the swoop.

And within the ‘B’ of the fourth line, again in the two swoops, “data markings” can be seen, he said.

“There are four numbers in that loop,” he said. “And there is something in the O, in the bottom right as it curves up and in the A, across the middle, and in the Q.

“What’s unusual is these smaller letters are shaped into the form of larger letters — I haven’t seen it before.”

He believes he’s solved some of the micro-writing’s significance — between and below the “SA” is “Venom X4621”.

“This resembles the number of an early tender document number for the de Havilland Venom, which was still on the drawing board in 1948,” he said.

The Venom was a British post-war aircraft.

And below the ‘AR’ is ‘LZ 5056’, which he thinks is a flight number of a Bulgarian Airlines flight from Sofia to London.

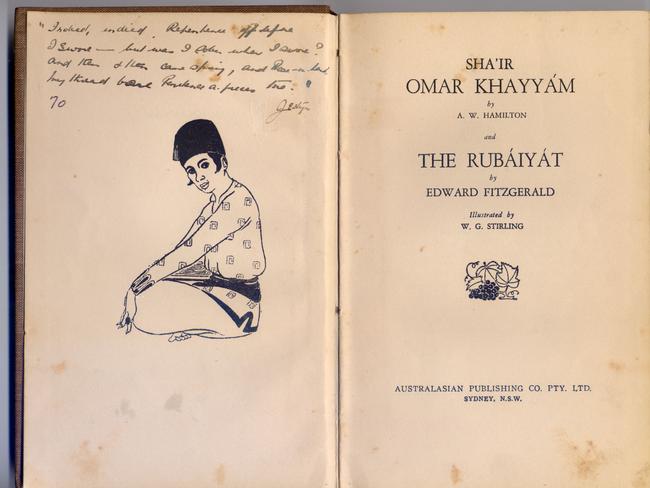

Micro-writing in code can also be found elsewhere, Mr Cramer said, in Alf Boxall’s copy of the Rubáiyát, given to him — and inscribed by — Jo Thomson.

The inscription, which she signed as Jestyn, contains more examples of code micro-writing, he said.

For Mr Cramer, it conclusively links the three people together as the heart of the entire mystery.

Mr Cramer believes the Somerton Man intercepted much of the code, because of where the Morse code prosigns fall.

He points to specific letters in the code, which he says mean certain things.

He believes the Somerton Man was not the code’s intended target, and that he probably intercepted it.

“In the top line, the ‘M’ signified the kind of message or the source. The ‘R’ normally means routine — there is no urgency,” he said.

“The ‘AB’ at the end of the line means “all before”.

“And ‘D’ is a prosign that means defer or deferred, which ties in with the R — this message is routine, it’s been deferred.”

The crossed-out second line appears to have been a mistake, although Mr Cramer says the line through it is actually four separate lines that look joined up.

In the third line, ‘T’ is a prosign that means transmit. The rest of the line is unbroken, while there is another ‘T’ at the end, followed by a dot and then a ‘P’ — or priority in the Morse code handbook.

The crossed lines in the centre were commonly used to signify two separate sessions of messages. Mr Cramer said the lines usually flowed back into each other at the other end.

The fourth line begins with “message” again, and is likely to be the corrected version of the second crossed-out second line, because of similarities in the LIA letters.

“It looks like they copied down a whole lot more detail for the fourth line,” he said.

“The ‘C’ at the end means ‘corrected version’.”

The fifth line begins with ‘V’ — or ‘from’.

“It’s a guess, but I wonder if the previous lines were content from someone else, they have been possibly intercepted,” Mr Cramer said. “And the summary existed in that last line. Normally you get the call sign that follows the ‘V’, which could be the TTM — or tango tango mike.

“T also means transmit, and the M could be referring to the standard Ms above.”

“At the end is AB — but the B is actually an R. It doesn’t look the other Bs. And AR means ‘this is my last message — a response is not required or expected’.”

There are several other oddities within the code — the first and third Ms are very stylised, while the second and fourth Ms are quite normal.

And the ‘S’ in the final lines is almost identical to the Aramaic ‘S’, which is a sign for water.

“I don’t think it’s possible that’s what it means — that one must be a coincidence,” he said.

Mr Cramer is now working with an American professor to further examine the micro-writing, but not everyone agrees with him.

Professor Derek Abbott, who has studied the Somerton Man case for years, remains unconvinced.

There isn’t enough resolution in the photo of the code to be sure, he said.

“My scepticism regarding micro-writing stems from the fact that these are getting into the resolution limit of the image,” he said.

“Further, the acid test for anything like this is that it should result in a message of significance. Until then, in my view, it remains unvalidated.”

The original piece of paper with the code has been lost.

Professor Abbott is urging the State Government to exhume the Somerton Man, to solve one of the other big mysteries — whether or not he and Jo Thompson had a child together.

In January, the family of the nurse, who died in 2007, told 60 Minutes she may have been a spy and had a son with the Somerton Man.

You can sign Professor Abbott’s exhumation petition here and read more about his extensive study into the case here.

You can read more at Gordon Cramer’s blog here.

----

Editor’s Note: The views and opinions expressed in the article are Gordon Cramer’s own and do not represent the views and opinions of the Association of Former Intelligence Officers, or its directors.