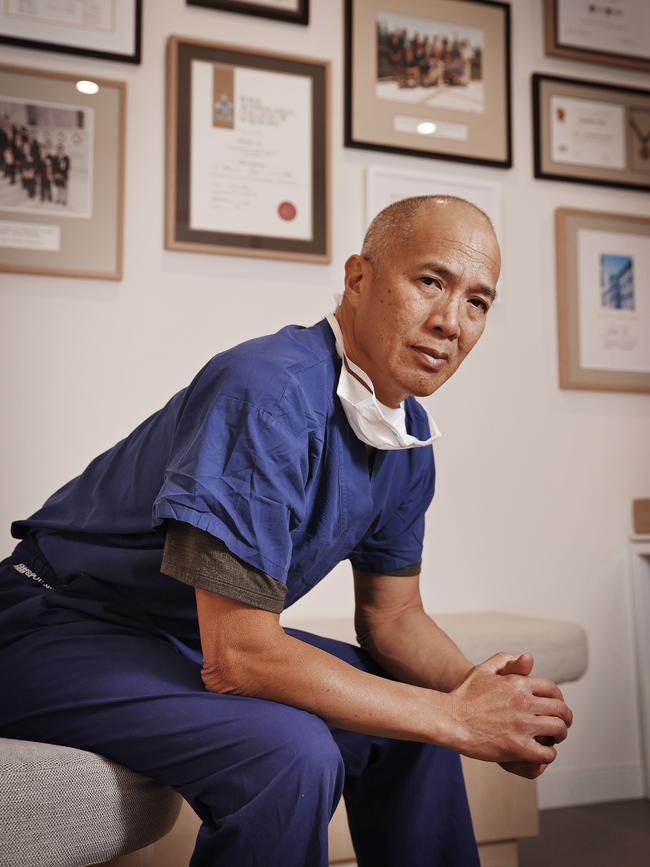

‘Going to destroy you’: Surgeon Charlie Teo on why they’re out to get him

Banished neurosurgeon Charlie Teo has revealed why he thinks his detractors are targeting him – and ripped into the state of Australia’s broken medical system.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Banished neurosurgeon Charlie Teo says the possibility of medical breakthroughs in Australia is hampered by a broken, dysfunctional system that fosters a legion of conservative doctors too risk-averse to challenge the status quo.

Dr Teo says medical authorities’ decision to effectively ban him from operating in Australia was effectively a warning to all young doctors that if they wanted to challenge conventional wisdom, they would be penalised.

In a wide-ranging interview with Mark Soderstrom on the podcast The Soda Room, Dr Teo, 64, outlines why he believes his detractors are out to “destroy” him and laments the state of the medical profession in Australia.

“You don’t have to have any other skill to get into medicine except for the ability to regurgitate knowledge,” he says.

“You have to be in the top half per cent of the state in your matriculation exam to get into medicine. That means people are getting into medicine without all those other skills like compassion. And kindness. And empathy. And communication skills.

SCROLL DOWN TO LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

“You then get a profession that encourages regurgitation of dogma, and not challenging the status quo. And then you become a doctor where you’ve got medical governing bodies saying that you can’t do anything out of the ordinary – you’ve got to toe the party line, you’ve got to get consensus from your colleagues and you’ve got to get evidence-based medicine.

“So you’ve got this whole vocation, now, of people who don’t want to challenge. Well, if they do, they get penalised for it.”

Dr Teo, who has built a practice by performing intricate surgery on tumours others thought inoperable, says his ban from operating in Australia sent a clear message to other doctors.

“The message we’re going to send out to all those other young doctors, is (if) you do what Charlie Teo does, this is what we want to do to you – we’re going to destroy you,” he says.

In August last year the NSW Medical Council imposed a series of conditions on Dr Teo’s practice after complaints about his methods and allegations he gave patients false hope. The council banned Dr Teo from performing high-risk surgeries without the written approval of a second independent neurosurgeon. The restrictions will remain in place until a hearing later this year.

Dr Teo has treated 11,000 patients over his 35-year career, raised more than $51m for brain cancer research through his charities and established the largest tumour bank in the southern hemisphere.

He tells Soderstrom he believes part of the reason some of his colleagues have set out to destroy him is because he hasn’t been shy about talking up his own ability.

“I think I’m a great surgeon,” he says. “I think I’ve got this amazing ability to take out tumours that other people can’t take out.”

Also on the podcast, Dr Teo:

* Says the saga of his banishment has left him with a “very jaded opinion of humanity” but he spent a few days with a guru in India who taught him that one day, the whole saga “would all make sense”

* Talks about being accused of giving patients false hope. He says there is no such thing as false hope – rather making false promises, a practice he agrees all doctors must avoid.

* Says every doctor should have their own foundation to raise money to stop disease.

* Says he is sure there will be a cure for cancer one day, and he wants to find a cure for brain cancer

* Says there is merit to the association between brain cancer and mobile phones.

CHARLIE TEO SPEAKS TO MARK SODERSTROM IN THE SODA ROOM

The Soda Room is presented in collaboration with the Sunday Mail.

Below is an edited transcript of the podcast – listen in full in the player above or click here to go to the site.

Mark Soderstrom: Charlie Teo, welcome along to what we call the Soda Room. It is a judgment-free zone where we just come and share stories.

Charlie Teo: Thank you Mark.

MS: Charlie, you’ve become world renowned because you will take on those unbelievably challenging jobs and a lot of the ones that other surgeons will say are inoperable. How can you and why can you do it? Are you more skilled? Are you more confident? Do you have more courage? How do you do what many others won’t?

CT: Look, the worst thing about being a doctor is that everyone wants you to eat humble pie. I’ve heard sportsmen on TV going, when the commentator says: “You played a good game there, what was it, do you, how did you beat your opponent?” And they go, “Well, you know, I was in peak physical condition, played a great game, and I had focus, and, you know, I think I was a better player on the day.” Well, you get a doctor who says, “You know, I’m a little bit more intelligent, and I’ve got greater tenacity, and I’ve got more skill. And I think I just took out that tumour because I’m a great surgeon.” Oh, my God …

MS: They’re going to say: “Wanker”. Straight away.

CT: Not only wanker, but your colleagues are going to listen to that and go: “We’re going to destroy you”. And I think that’s part of my problem – that I haven’t been a wilting flower. I haven’t said that, you know, that it’s pure luck … I think I’m a great surgeon, I think I’ve got this amazing ability to take out tumours that other people can’t take out. Be it tenacity, 3D perception, a still hand, no tremor. I don’t know what it is. Courage? You know, it’s probably a combination of all those things. Because I’ve seen other doctors who are technically better than me. I’ve seen other doctors who have amazing dexterity or 3D perception way better than mine. But, you know, you’ve got to have the combination of courage, tenacity, skill, experience, knowledge, 3d perception, you know, all of those things.

MS: If you get a patient who obviously has brain cancer, and they say, I want you to do whatever you can, would you always do an operation, or are there times when you’d say, you know, what, there’s actually no point me operating?

CT: It’s more complicated than that. And a lot of the problems that I’ve had with my critics has been because they haven’t been in that room, having that discussion. And that discussion, is … it’s multifaceted. By way of example, when a neurosurgeon comes to train with me, I get them to see a patient and then present that patient to me. And so often the doctors come and go: “This is a 36-year-old man who presents with a three-month history of …” and I go: “Stop right there”. I want to know who that patient is. So I want to know what they do for a living. I want to know their social circumstances, who supports them, what their hobbies are. I want to know their appetite for risk. I want to know about their quality of life and how they measure their quality of life. And so, you know, sure, it’s one thing telling me that their cranial nerve six doesn’t work so well – that’s fine. You’ve got to know that, but I really want to know the person. And that is part of my decision-making, where I actually, I see it as not a tumour in the frontal lobe, but I see it as a young guy who’s got no social network, his whole life is physical … and then you can go okay, well, this operation can potentially ruin your ability to be independent and enjoy life because it could potentially paralyse you. And then so then you’ve got to start pulling your punches and saying, in my opinion, in my opinion, I think the risk-benefit ratio is such that I’m not going to recommend surgery, right? But then I always go on to say, look, you’ve got my opinion, I’m not recommending surgery, I think it’s too risky for your benefit. But if you really want it, I’m on your team. I believe in patient autonomy. I believe that you should respect the wishes of your patient. And as long as they’re well informed. Now again, a lot of my critics go, well, that’s all well and good, Charlie, but you can always sway someone one way or the other. And it’s absolutely true, you can. You can make it sound really risky or not risky, and you can influence someone’s decision making. So they’re absolutely right. It’s really important. It’s incumbent on the doctor, to be honest, and to be as objective as possible in their informed consent. And then you can allow the patient that make the decision.

MS: So surely there are instances where you will not operate. Even if a client or a patient says look I want you to do it?

CT: Yes, it happens rarely. But of course there are some tumours that you know full well that the risk-benefit ratio isn’t even a ratio. There is no benefit and there’s all risk. And so yes, there’s a tumour called a DIPG for example, otherwise known as diffuse midline glioma, or diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. It’s a tumour where the brain itself is interspersed amongst a tumour, and it’s not separate. It’s almost as if the tumour is like pushing against normal brain. And I have a lot of those patients with DIPGs coming to me and saying, you know, we understand you’re a brain stem surgeon and you take our brain stem tumours that others don’t take out, please, can you take out this tumour? And I say to them, absolutely not. I won’t do it, I won’t do it, because there’s no benefit.

MS: Do you have self doubt? In your professional world and decisions that you make?

CT: Look, I get my fair share of bad outcomes, believe me. I do the world’s most difficult tumours. And of course, I’m gonna have some bad outcomes. I’ve never said I’m perfect. And when I get a bad outcome, of course, it hurts me, it hurts me. You know, sometimes I cry, I openly sob when I’m by myself, thinking, oh my God, I’ve ruined that person’s life, or I’ve taken that person’s speech away, or their vision away, or their arm away or, and sometimes, you know, you’ve even taken their quality of life away. And so you got to live with that, remember, so it’s something that you can never, ever downplay, or you can never forget it. It’s stuck with you forever. And so as a neurosurgeon, you’ve got to constantly say to yourself, I tried my best. As long as you have tried your best.

MS: Do they teach psychology to you in medical school? Because it sounds like beyond being a neurosurgeon you are a psychologist, you’re a counsellor, you’re all these other things? Do all the doctors have those skills to be able to make those decisions?

CT: Why do you think doctors aren’t at the top of the most trusted profession anymore? I’m gonna get in a lot of trouble saying this. But in the olden days, people got into medicine because they wanted to help people. That was a major driving force. You know, I want to help people, I want to do medicine. And they could get in because there weren’t many, that many altruistic people around. And it was relatively easy to get into medicine. If you think about it now, you don’t have to have any other skill to get into medicine, except for the ability to regurgitate knowledge. So you have to be in the top half per cent of the state in your matriculation exam to get into medicine. So that means that people are getting into medicine without all those other skills like compassion, and kindness, and empathy and communication skills. They’re getting in simply because they’re so smart, that they’ve managed to get the marks to get in. So you have people who can regurgitate knowledge getting into medicine. You then get a profession that encourages regurgitation of dogma, and not challenging the status quo. And then you become a doctor where you’ve got medical governing bodies saying that you can’t do anything outside the ordinary. You’ve got to toe the party line. You’ve got to get consensus from your colleagues and you’ve got to get evidence-based medicine. So you’ve got this whole vocation now of people who don’t want to challenge Well, if they do, they get penalised for it. So it’s been drummed into them don’t challenge the status quo. Don’t do anything that’s not got evidence to back you up. And so this is stagnation of medicine. People aren’t challenging the status quo, and they’re not doing things that are a little bit left field.

MS: Sounds to me like, as someone with no real knowledge in that area though, that you don’t get change. You don’t get evolution, you don’t get development, you don’t get new techniques created if you can’t challenge a conservative establishment.

CT: That’s what’s happening. Look what’s happening to Charlie Teo, you know, you be a Charlie Teo, and the message we’re gonna send out to all those other young doctors is you do what Charlie Teo does. And this is what we want to do to you, we’re going to destroy you.

MS: So look, as many people know the medical board in New South Wales has put these onerous restraints on you because of certain complaints or reasons. So that essentially you can’t operate in Australia?

CT: It’s almost impossible for me to operate in Australia. But it’s more complicated than that. I could go on for ages and ages, and it’s too negative. So I won’t talk about it too much. But it goes like this. The system is broken. It’s a dysfunctional system whereby a competitor can make a vexatious complaint about you, you are immediately presumed to be guilty. And then you’ve got to prove your innocence to the very person who complained about you. How can that system work? It’s like Coles making a complaint about Woolworths. And then Woolworths goes, well hang on … who’s going to judge that? Oh, let’s get the Coles person to judge that? So I’m being judged by my competitors, who are the very people who made the complaint about me in the first place. How can you have a fair system or due process when you’ve got that antiquated and an unfair set of rules.

MS: So the ability to do what you love doing, and which clearly there are thousands and thousands of people who have benefited from and would provide testimonies for you, if that’s removed from you at the moment, how do you cope with that because this is who you are, this is what you do. This is what you love. How do you deal with that mentally?

CT: Well, like I’ve never really felt melancholic. No, actually I haven’t been sad. I’ve been angry. It’s mostly anger at the sadness of the situation. So the sadness of the situation is that my entire practice was mostly taking out tumours that other people called inoperable, so that was 90 per cent of my practice. That’s 10 tumours a week. So that means, quite conceivably, that there are nine patients a week, who are missing out on either extension of life or cure from a condition that I know that I can help. Now that’s sad. The good news is that, at this moment, I can operate overseas, the Australian rules don’t apply to overseas.

MS: How can you reconcile all of this? Are you coping, okay, this from a point of view of you as a person.

CT: The sad thing is that I’m getting a very jaded opinion of humanity. I mean, that’s sad. It’d be, it’d be nice to think that most humans are nice people, and there’s the occasional evil one. But the more evil that you witness in life, the more you realise, well, maybe humans are evil, and there is occasionally a good one. That’s sad that I’m thinking that way. The other thing is, I got to a stage where I was getting palpitations, I was getting really angry. And, and so I went and saw a guru when I was in India operating. I do a lot of charity work in India and do a lot of pro bono work there. And I thought, well, look, a lot of people go to India to find themselves and they have a great philosophy. So I met with the guru, spent a few days with him. And we went through all of this. And I must say that it really made me come out the other end in a better place. And if you want to distil what he told me, it was this: “Charlie, one day, it’ll all make sense. It’ll all make sense one day.” And that’s an old story of, you know, one door closes, another one opens, and, you know, cream always rises to the top. And they’re all those sayings that basically says: “Look, you know, what is a hurdle now will become a stepping stone.” And I just have to think that that maybe, maybe there’s greater things to do and better things to do. It’s all very sad. And I feel so sorry for the patients because I know that I can help them.

MS: Can you tell me about hope? Because obviously, some people say false hope, but tell me is it false hope if you can prolong someone’s life?

CT: Yeah, look, like if you’re a Charlie Teo detractor, then they’re accusing me of false hope. Now, what does that mean? So this is what it means. There is no such thing as false hope. Hope is something that we all hold on to on a daily basis. I mean, you’ve got to hope that you’re alive the next day, if you want to go to bed at peace. You’ve got to hope that you can cross the road without being killed. There’s no such thing as false hope, we all have hope and hope is what drives us on a daily basis to live our lives. What they’re talking about is false promises from doctors to give people hope. And I 100 per cent agree with that. I think it’s incumbent on a surgeon or a doctor not to give false promises, so that people can either cling on to hope or let go of hope. It’s up to them, as long as you inform them properly. So they’re accusing me of giving false promises. They’re saying Teo operates on tumours that no one can operate on and he’s doing for money, or he’s doing it for glory, or, you know, whatever they accused me of. So they’ve, they’ve missed worded it, essentially. Because there’s no such thing as false hope, only you know, false promises.

MS: Charlie Teo, thank you so much for joining me, it’s been an absolute treat. And I could sit there and talk to you for hours. Thanks so much for joining us.

CT: Thank you. Thanks very much