From Tiger cub to Lion king: Lachie Neale’s journey from tiny farming community of Kybybolite

There’s no pub, store, school or town hall but by Sunday night Kybybolite had a Brownlow Medallist. Reece Homfray charts the rise and rise of Lachie Neale from very humble beginnings.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- SA Brisbane Lions player Lachie Neale crowned Brownlow medallist

- Picture special: Brownlow champ’s wife steals the show

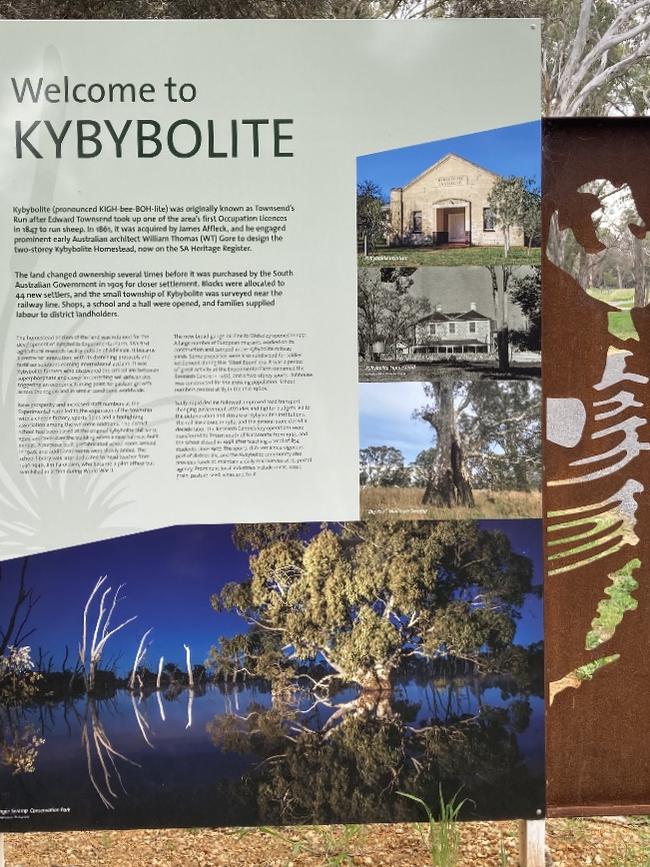

Kybybolite is the town with no pub, general store, school, rail line or town hall and a population of less than 200 scattered about on neighbouring farms, but by Sunday night it boasted a Brownlow Medallist.

“Apart from a few dozen houses all that’s left in the town is the footy club and the CFS shed,” Kybybolite Tigers under-17 coach Andrew Shepherd said.

“And without the footy club the town just about doesn’t exist.”

Known by locals simply as “Kyby”, the farming community lies 340km south-east of Adelaide on the South Australia/Victoria border and has produced Brisbane Lions midfielder Lachie Neale, crowned the 2020 Brownlow Medallist on Sunday night.

Neale’s football career has taken him to Adelaide — where he played with Glenelg — and now Brisbane via Perth where he was drafted to Fremantle, but Kybybolite remains his home. So much so that when the AFL season went into shutdown in March, Neale and his wife Jules and their dog drove 2000km back to the family farm before the borders closed.

“The local oval is looking in pretty good nick so I’ve been down there a couple of times, haven’t had a kick yet but my sister likes playing netball so I’ve been there with her,” Neale told The Advertiser at the time.

“I’ve been fishing and hunting with my little brother and we brought the dog as well and he’s loving it. It’s good fun to chuck a lure in the dam and see if we can catch a few.”

Watch the 2020 Toyota AFL Finals Series on Kayo with every game before the Grand Final Live & On-Demand. New to Kayo? Get your 14-day free trial & start streaming instantly >

The two-storey clubrooms at Kyby Oval is the jewel in the town’s crown. Built by volunteers in 1974 — the year of its last senior premiership — it has outlasted even the school which closed in 1998 and the town hall which was sold and renovated as a private residence.

“The footy club has got such a proud history everyone has made sure we’ve kept it going,” Shepherd said.

“Family farms aren’t as big as they used to be so local farms aren’t carrying the families they once were, so where the Kyby Footy Club was made up of very much local farming families now we rely on them coming from the broader community and Naracoorte itself.”

Twenty years ago, two of those families who were part of the furniture at the footy club were the Neales and the Trengoves.

Jack Trengove went to school at Naracoorte North and Neale at Naracoorte South, but despite the two-year age gap they played in the same teams at Kybybolite where Trengove’s dad Colin had played and Neale’s dad Robbie, or “Scratcher”, was coaching.

“I’ve known Lachie my whole life,” Trengove said.

“My mum and sisters were playing netball there as well so from as far back as I can remember, Lachie and I would always be out there watching the A-grade team train on a Thursday night.

“We’d be the only two kids out there and kicking the footy together and kicking goals for hours on end.

“Dad’s got old footage of A-grade games at halftime where Lachie and I were running around together before we became old enough to play in the junior colts.

“Because he was younger in a grade above and always so small, at the same time he embraced that and saw it as a challenge if anything.

“He was running around with blokes like myself who are a couple of years older than him so he had to rise to the occasion if he wanted to compete, especially in country footy you’re always playing above your weight.

“My first year with him was in the under-14s. I would have been 12 and he would have been 10 and he started in the forward pocket but as he got older he progressively moved to the midfield and from the outset you could tell he had some serious skill and ability to find the football.

“To think back now to all those Thursday nights when we’d be out there kicking the footy until the lights went out, to see him get drafted as the last pick pretty much in his draft year, have a successful time at Freo and go to another level at Brisbane and now pretty much be one of the best players in the comp … if you think back to where it all started it’s an incredible effort.

“And he had so many doubters early on, so to have proven them wrong is a serious credit to him.”

Jamie Kelly coached Neale at Kybybolite for two years as a kid and remembers him as “very small and very determined”.

“He had an incredible determination to get the footy, that competitive nature that all the good players need to have,” Kelly said.

“But back then he would have only been a flanker because we had one hell of a side — Jack Trengove (drafted to Melbourne) was in it, Alex Forster (drafted to Fremantle) and a few others who played league footy including Andrew Bradley who has captained Glenelg.

“It’s remarkable to have that talent in an under-14 side in a very small town, and they were all mates, always carried footies with them, they were mad on football. Not least of all, Lachie.”

David Noble is the general manager of football at the Brisbane Lions and said knowing that kids from the country had played against bigger bodies from a young age was usually a telltale sign for recruiters that they’d make good AFL players if they also had the skill.

But Neale still slid to pick No. 58 in the 2011 national draft when the Dockers took a punt on the pint-sized midfielder.

“The really good ones solve problems well, in some cases it’s not just how to extract the ball but how to play a different type of opponent, and one of his (Neale) great traits is he makes good decisions in games about how to position or align himself against a different opponent,” Noble said.

“As recruiters we like the ones from the country because they generally play up a level, or if you’re a junior you’re playing seniors, and that helps you make those decisions. Your decision making process has been worked on from a very early age because you’re a country boy.

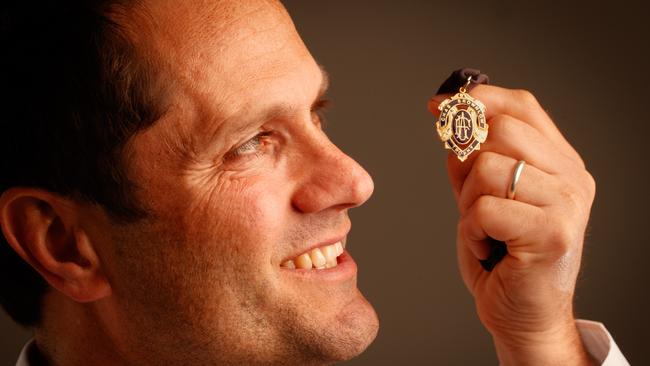

“I remember him winning the Alan Stewart Medal in that under-18 grand final (for Glenelg) and his execution in that game was just elite.”

Noble was at the Crows when former recruiter Matt Rendell now claims he tried to convince them to draft Neale despite his lack of height, but they passed.

“I liked what he was doing and we did have him on our list. I think “Bundy” (Rendell) wanted to push him up a bit higher, and the proof is in the pudding now that he’s right. He was pushing him pretty hard,” Noble said.

“I didn’t get him the first time but got him the second (at Brisbane).

“What he’s brought to the table (at the Lions) is an inward drive that he wants to make people better around him, he does a lot of work around on his game, but the essence of why he does that is to make others better around him, for instance his hands or his ability to help us on the scoreboard. That’s the ultimate team professional.

“He’s pretty dry and witty, he’s got a good sense of humour, he’s your classic country boy who has time for everybody, always stops and says hello and he’s a pretty witty young man.”

A few years ago Neale, Trengove and his sister Jess, went back to Kybybolite to speak to the club’s juniors about having a dream and chasing it.

There were a few Fremantle jumpers getting around and while Shepherd said not many have ditched them for Brisbane ones now, the entire club keeps a close eye on Neale and was glued to the live stream of the Brownlow Medal on Sunday night.

“Everyone is always talking about him and I don’t think there’d be too many kids who don’t follow how he’s going,” Shepherd said.

“Kyby is such a small place that everyone knows everyone. He’s come back to the local primary school a couple of times at Naracoorte and he came back during the Covid break this year and he and his stepbrother and sister were down at the footy club having a few kicks and practising their netball shots.

“We certainly cherish that and so does he.”

BROWNLOW WIN A DREAM COME TRUE FOR NEALE

Robert Craddock

Long before he dreamt of being a Brisbane Lions premiership winner, Lachie Neale dreamt of being Gavin Wanganeen.

Speaking ahead of Neale’s Brownlow win, boyhood hero Wanganeen said it would warm his heart if “the little warrior’’ joined him as a winner of the code’s most cherished individual award.

The Brownlow and a Brisbane Lions premiership would be an earth-quaking, dream double for Neale – for a journey which started on a farm in the tiny South Australian town of Kybybolite (population 107), where he cheered for Port Adelaide and their debonair star Wanganeen.

“I dreamt about being Gavin, but his skills are much silkier than mine,’’ Neale said.

Wanganeen is flattered.

“Well, I am not sure about that,’’ he said from Adelaide.

“So he said I inspired him? Wow. I feel really proud. It warms my heart. He is a great little warrior.

“I’ve been watching him since he was at Fremantle and always thought he was a beautiful fast, running attacking midfielder.

“I always sensed he would get even better. He’s a ball magnet.

“You could tell he had that work rate and hunger. You don’t get that amount of ball if you are not hungry.

“I think opponents are surprised how strong he is.

“He would be a very worthy Brownlow Medal winner. If he wins it I think they probably got it right.

“He has had one of those out of the box seasons.

“His possessions really count. They are not cheap possessions.’’

Test cricketer Kerry O’Keeffe got laughs across the panel on Fox Sport’s Back Page recently when he said most of the recent Brownlow Medallists had come from towns without McDonald’s, but behind the dry quip there was a telling tale.

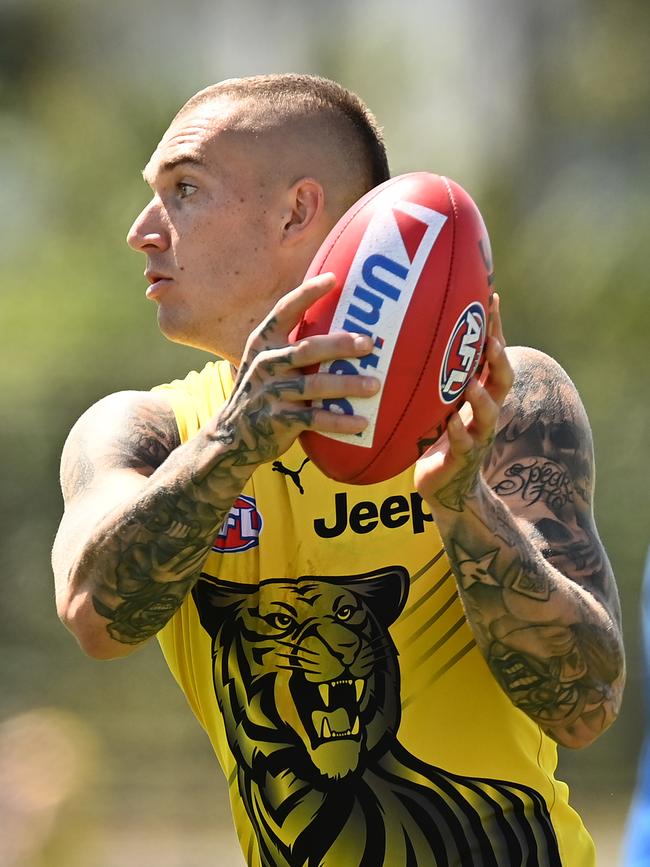

There is a pattern in country-raised recent winners like Nat Fyfe, Dustin Martin and Matt Priddis spending their early years in wide open spaces rather than wide open cyber space.

“They sort of came in a fraction before the social media frenzy and technology which would take their minds away from playing sport,’’ Wanganeen said.

Like many country-raised children, Neale played endless games of football, cricket, basketball and tennis so that by the time he reached senior level his moves were as instinctive as a touch typist’s.

He felt basketball, in particular, gave him a spatial awareness that he benefits from in football.

Neale’s hand skills are so subtle he has a trick where he can make a clapping sound with one hand and part of his pre-match routine is to juggle three tennis balls.

But no footballer gets it all.

When asked if there was a skill he could steal from a rival, he does not think long before saying: “Nat Fyfe’s aerial skills or Dustin Martin’s bump”.

An old-fashioned football nuffy, too much AFL is never enough for him.

When he is not playing he is normally glued to the match of the day and he is something of an information junkie in exchanges with coach Chris Fagan because he hopes to coach when his playing days are over.

“I like that side of the game and hope to be involved post footy and Fages has been a good mentor for me in that space.’’

“He is often calling up sharing with me things he is thinking about.’’

It was Neale’s fascination with watching other games that made him welcome to an approach to making a surprise and unexpected switch from Fremantle to the Lions.

“I watched a fair bit of their games and while they were not winning but they were only losing by two or three goals and you could see they were on the verge of breaking through. I was really impressed with the young core of guys coming through.

“I knew they would be a good side fairly quickly.’’

And so they were.

Originally published as From Tiger cub to Lion king: Lachie Neale’s journey from tiny farming community of Kybybolite