From morse code to smartphones and everything in between

FROM Morse code, to car phones that took up half the boot, to smartphones — how we communicate has come a long way. Retired Adelaide newsman Bob Perry looks back at the early days.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- When newsreels were on before movies at the cinema

- Bob Byrne’s new book, the best of his Boomer columns

- Amazing photos of the Adelaide Railway Station

- The reason why this statue is on Hindley St

BELIEVE it or not, young people, once upon a time there were no mobile phones.

When I was a boy, most houses didn’t have a phone and before that nobody had a telephone.

In the early days of Adelaide, the only way to get an urgent message to someone was to run, or ride a horse, and pass the message face-to-face.

Around 1850, if there was a fire, someone would run to the police barracks on North Tce, the duty inspector would send out an officer on horseback to find the constables walking the beat. He would then send them running back to the police barracks to collect the fire pump and either tow it by hand or hitch it to horses and gallop to the fire. Just imagine how long that would take.

As most of Adelaide’s buildings were made of wood and thatch, there wouldn’t be much of the structure left by the time they got water.

When the telegraph was introduced, a message could be sent to a post office using morse code and the message could be delivered by hand. Amazing!

A slight digression. When I started work at 5AD in 1959, and through the 1960s, we were still using morse code to communicate with the regional stations 5PI, 5MU and 5SE.

I got 10 shillings a week to know and use morse code.

Once the telephone came to Adelaide, only government offices and important businesses had the telephone connected.

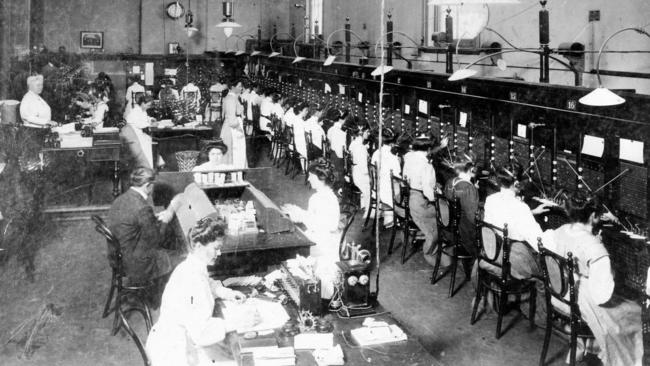

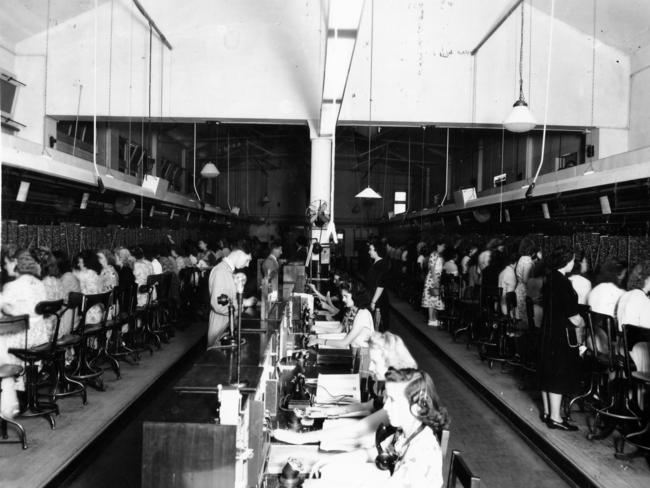

You didn’t dial a number yourself, you contacted the “operator” in the telephone exchange by winding a little handle and she connected you.

Once people saw how convenient these phone things were, there was a demand.

Even the public wanted to use them, so public phones were introduced, and then phone boxes.

Throughout the city, little steel poles were erected with a box on top. They were police boxes, and suddenly police on the beat were in contact with the City Police Station.

Each officer had a key and they could be alerted or pass messages. It was a revolution.

Later, taxis caught on, and each taxi rank had a series of different coloured boxes to cover the various companies.

Taxis now didn’t have to go back to their depot to get a job.

Not many people could afford to have their own phone. I can remember we would walk about 25 houses away to Mrs Smith, who had a phone for an emergency, or we’d ride a bike around to Henderson’s grocer shop for the nearest phone box.

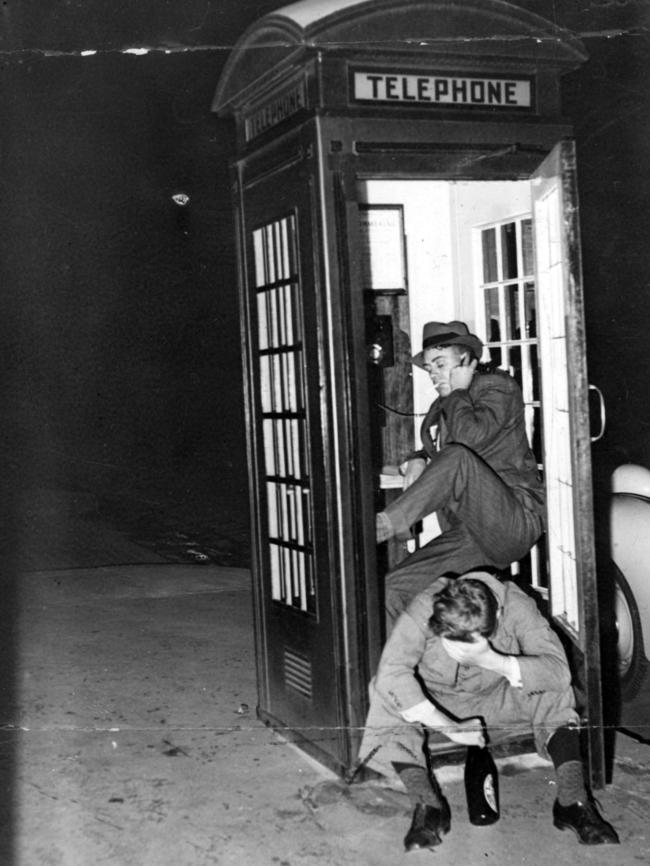

At times, there would be a queue of people waiting to use the phone, and people would cough loudly or even bang on the tiny windows of the phone box if the person using the phone was taking too long.

Initially, these phones were connected through an operator, who sat in rows like battery chickens at the Central Exchange, plugging little patch cords into sockets and talking to other operators around the world. Some times they listened in by accident.

They would tell you how much the call would cost for three minutes and you would line the coins up in a little slot on top of the phone and then press the button when you were told to.

After the three minutes were up, the operator would cut into the conversation with “three minutes. Are you extending?”, and you’d hang up or put in more money.

Later, when it was an automatic system, we had the “A” and “B” button phones where your money disappeared and may, or may not, come out if you didn’t get through to the person you were calling.

People used to pop into phone boxes just to check the slot to see if someone had left money in there.

In the book of the history of the St John Ambulance Brigade in South Australia, they talk about the early ambos having two pennies soldered to a piece of wire, which they kept in their pocket.

The idea was that they had to phone in for jobs, so they would feed the pennies in, make their call, then pull the pennies out. The book is called Two Pennies and a Piece of Wire.

I’d suggest they weren’t the only people doing this.

In the early days of radio, we’d clip wires across the terminals at the top of the phone box to feed back interviews we’d recorded on cassette decks.

But at least we’d paid for the call.

Eventually, home telephones became commonplace, emergency vehicles had radios, and even planes no longer had to look to the control tower for a flag to tell them when they could take off.

What a revolution when pagers came along. I had one that went “beep, beep, beep” when the ABC wanted me or “beeeeeep” when it was Channel 9.

My first car phone took up half of the boot of my car.

There were only 50 car phones allowed in Adelaide and you almost had to wait for someone to die before you could get one.

Ex-SANFL footy player and car dealer Ken Eustice didn’t die but he no longer wanted to be contactable in his car, so I bought his phone.

Only one person at a time could use the service, so you listened to see if anyone was using the phone, pushed a button and an operator connected you.

It was handy for a freelance TV news cameraman but I still couldn’t see any hilarious YouTube videos.

The first portable phones were the famous “bricks”, which weighed nearly a kilogram and cost $5200 in 1987 money (12,179 today).

Within a few years you had a phone that would fit in your pocket, portable satellite phones and then the “smart phone”.

Now you cannot only talk clearly to someone across the world, you also can see if they’re wearing clothes or not.

We’ve come a long way from morse code.

Bob Perry is a former cameraman and journalist who has worked for all Adelaide TV stations, including 14 years at Channel 9