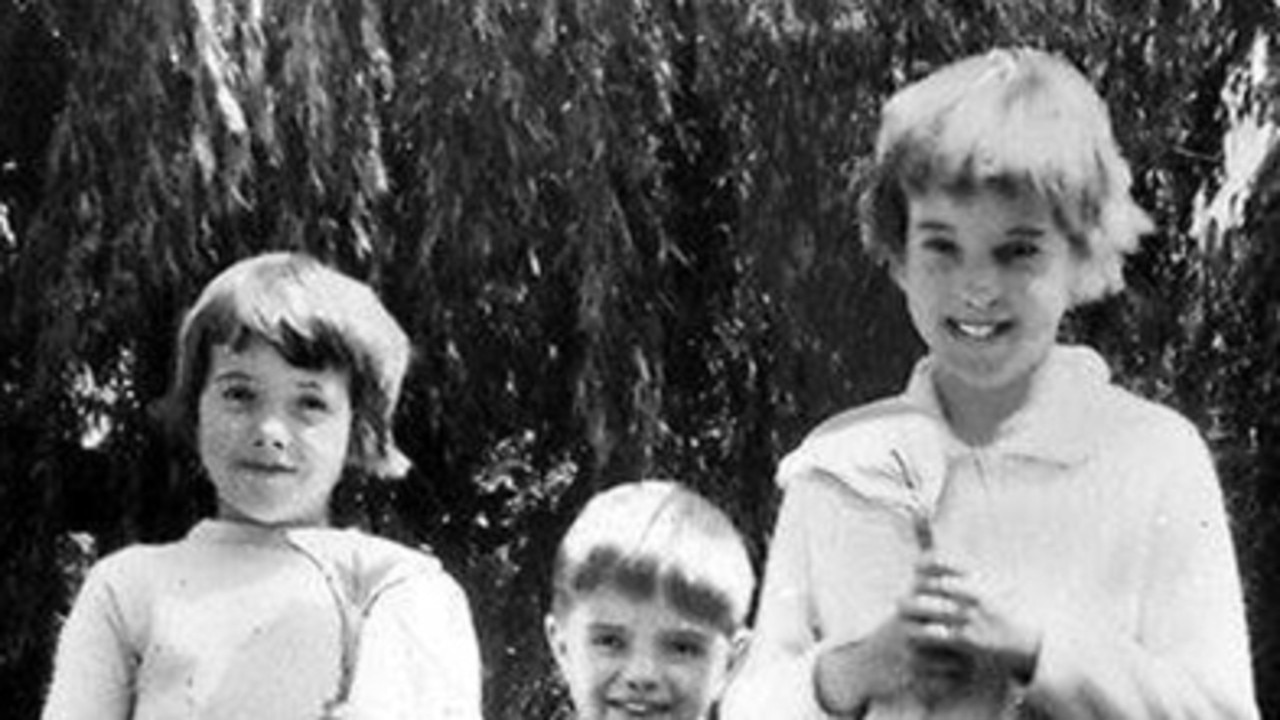

Forever four — but Ella Wood’s legacy lives on through the Road Trauma Support Team

Ella was just four years old when she died. She was also my friend. This is her story, and how her short life has helped thousands of SA families through their grief.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Tributes after a fatal road crash often begin with similar words: “bright, bubbly and full of life”.

But it’s rare as a journalist to be able to speak to the infallible truth of that description.

Or to tell the story of an inquisitive, lively preschooler who never grew up — but has changed the lives of thousands of South Australians in the 24 years since her death.

Four-year-old Ella Wood died on August 31, 1999, after she was hit by a reversing car in a shopping centre car park at Aldgate.

She was also one of my best friends.

There are few people in our state who understand the way our road trauma victim response has been shaped by her death. Many of them are the families of the 101 lives lost on our roads this year.

Most of them have only learnt of her impact on the worst day of their life.

At the time Ella died, there was no dedicated service within SA Police to provide support for families of road trauma victims. Ella’s mum, Robyn-Lynn Wood, knew that needed to change.

“When it happened, it was a gut punch,” she said.

“You don’t believe it and you can never be prepared for it — and you’ll never get over it.

“It was crazy to me that there was no help.

“There were all the campaigns about road trauma and preventing crashes, but after you’ve swept up the mess on the road, who was fixing the mess of the people left behind? There was nobody.

“They actually pulled in two ladies from the homicide support group for us because there wasn’t anything else at the time.

“One of those women said to me: ‘There’s nothing for people, so maybe it’s time to turn what happened to Ella into a positive’.”

By January 2000, Robyn-Lynn and a close-knit group of passionate, professional women she calls friends to this day had launched the Ella Wood Fairy Foundation — with one, four-year-old powerhouse driving their united dream.

“We wanted Ella to be the last person to die on the roads where there wasn’t any help available,” she said.

“They all helped me develop a committee to look at what services were missing.”

The SA Police family soon became closely entangled with the foundation, which provided support not just to families of crash victims, but first responders and the officers tasked with delivering the devastating, life-altering news.

“One officer said to me: ‘We’d go to a house and we could see them sitting there eating fish and chips. We knew they would never finish enjoying those fish and chips once we knocked on that door’,” Robyn-Lynn said.

“Every single officer knew just how important it was to deliver that news and knew that whatever they said would be changing that person’s life.

“There was one police officer who, when I went to speak to their station, was inconsolable.

“That really resonated with me, what these crashes do to emergency services.

“I just said to him: ‘I’m still here, I’m surviving’.”

Volunteers from all walks of life began fundraising to help the charity provide critically-needed services.

“It wasn’t just counselling — we developed baskets as well to take to families for children who had been traumatised by ambulances, accidents or the aftermath,” Robyn-Lynn said.

“It was little things like colouring in books and pencils, tea, coffee and long-life milk, notepads, envelopes, stamps and taxi vouchers.

“We also gave ‘Ella bears’ – teddy bears for children impacted by crashes.

“I worked in Colonel Light Gardens and police and offenders at the corrections centre would, instead of going out on the bus and picking up litter, work in the corrections room and make funky fairies and things for us to sell at fetes, traffic lights out of wood, to make the money we need.”

At the time, both Tasmania and Victoria had a Road Trauma Support Team providing services for crash victims, but nothing of the sort existed in SA.

“I would go out and talk to everybody and anybody begging for funding, saying, ‘please, please, we need this service’,” Robyn-Lynn said.

“The fact is, people need to get free counselling, people need to have a support person, people need that person to go to court.”

Robyn-Lynn’s lobbying led to the appointment of SA’s first Commissioner for Victims’ Rights Michael O’Connell in 2006 — a former police officer who also served as the state’s inaugural victim of crime and victim impact statement co-ordinator — and secured funding for what became SA’s Road Trauma Support Team (RTST).

To this day, a team of RTST volunteers provides invaluable support and free counselling to those impacted by crashes, including family members of victims, witnesses, first responders and even family members of the perpetrator – or, rarely, the perpetrator themselves.

While Robyn-Lynn has now stepped down from the foundation, those who loved Ella will never forget the four special years she had on this earth.

And as Ella’s legacy lives on through the RTST, neither will those in our state whose lives are irreversibly touched by tragedy.

“Ella was so unique, she was so full of life — she was such a chatterbox and a performer, she was everything to us,” Robyn-Lynn said.

“She had so much life and it was snuffed out immediately.

“She loved lollies. She had eaten a whole packet of musk lollies that her grandma gave her just before she arrived back at the carpark — and I’m so glad she ate the whole lot.

“She was loving and loved, as are all those who are taken too early, whether they are four or 84.

“Ella represents hope that she was the last victim of road trauma in SA who was a statistic.”

‘A trauma different to grief’

For the families of victims, the knock on the door on that fatal day is only the beginning of their trauma – something few know better than psychologist Jo Hamilton, a road trauma specialist who was one of Robyn-Lynn’s friends that volunteered their time during the RTST’s conception.

Ms Hamilton, who has provided support to the families of some of the state’s most prolific crash victims for the past 20 years, said the impacts of road trauma extended far beyond the usual grieving process.

“Grief and trauma are very different things,” she said.

“(Families of crash victims) often have all the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, which you don’t have if you’re grieving a death such as your grandpa or grandma.

“Because of the suddenness of it, and the way trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder works, you have these extra layers of re-experiencing it, avoidance, emotional shutdown and hyper-vigilance.

“Even if they didn’t see the accident, they imagine it, visualise it, have nightmares and dreams about the accident because of the stories they have heard or images that their brains have unhelpfully created for them.”

Ms Hamilton said, with most road trauma, there was an inevitable time period when the love and care of the community – through no fault of loved ones’ own – can start to fade.

But for families impacted by trauma, the grief will likely never leave them.

She said clients often came to her in the months, or even years, after the accident.

“In all trauma there seems to be this consistent three month period where people expect that you would begin to move on – but in my experience, these families are grieving forever,” she said.

“You can still see people crying every day for the first 12 months, and maybe a little bit less after that, but our society doesn’t recognise that.

“Families of victims often don’t want to burden their loved ones – but there’s no ‘fixing’.

“I’ve got people I’ve been seeing on and off for years who say they’re still grieving – I say, ‘Of course you’re still grieving’.”

It isn’t just the crash itself that can alter loved ones’ lives forever.

For many victims, Ms Hamilton said, the trauma can be exacerbated by lengthy – and often devastating – court processes.

“Major Crash investigators are so supportive of the people they work with, but they need lots of information,” she said.

“I have to say to clients upfront: ‘I’m going to tell you something really difficult to hear – you won’t get justice, you will get a legal outcome’.

“They need to be prepared right from the start, that if they’ve invested in the outcome in terms of getting some satisfaction or closure, it’s very unlikely.

“It can open up a world of harm and hate.”

Ms Hamilton said it wasn’t just the families of those who die on our roads who need support, it was also the “forgotten victims” – those who suffer life-changing injuries, or first responders who witness the unfathomable aftermath of fatal crashes.

“Those are the stories that are rarely made public, but they are the silent majority of those impacted by road trauma,” she said.

“I see a lot of witnesses of car accidents who are private citizens, because it’s often members of the public who are there first and might see a young kid lose their life.

“In the end, for so many people involved in these accidents, it is so awful that you can’t mitigate it – all you can do is try and help people navigate the awfulness and the horror in their own way.”