Fights, thieves and knives: The strange tale of SA oysters

Adelaide is a city built on oysters. Literally. It’s just one of the weird ways the colony of South Australia owes the humble oyster that fed it — and its forebears — for decades.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Adelaide is a city built on oysters. Literally.

Oyster shells from the vast reefs that thrived in our shallow seas were burned to make lime which went into the oyster cement that built some of our earliest buildings.

But before they went into our bricks and mortar they went into our stomachs, a valuable and abundant food source that played a vital role in feeding the young colony.

Go back further still and the mud oysters — Ostrea angasi — feed the indigenous people of the Adelaide plains, a fact evident in the shellfish middens that date back thousands of years. Across the entire southern coastline of Australia the oysters fed countless generations of Aboriginal people, their shells piling up over millennia in the swales of coastal dunes that hosted seafood feasts.

Speaking about the Port River region, Ngarrindjeri-Kaurna woman Veronica Brodie told academic Mary-Anne Gale: “There were mangroves down at Glanville and Port Adelaide before the wharves were built. Those mangroves were a source of food for the Kaurna people who lived there. They used to take lobsters (ngaultaltya) out of the Port River. Grandmother also told me they used to get shellfish — mussels (kakirra) and oysters.”

Before European settlement the native oyster reefs off the southern coast of Australia were huge. Truly huge. Hectares of oysters clumped together in our cool bays, protecting the sea floor and providing a home for fish and other life. It’s believed that there was 1600km of oyster reef along the South Australian coastline alone.

Indeed the oysters were in such abundance that they even proved to be a navigation hazard to early sailors, as this 1791 journal entry from British mariner George Vancouver, who was exploring the waters around Albany, WA, shows:

“In our way out of this harbour, the boats grounded on a bank we had not before perceived; this was covered with oysters of a most delicious flavour, on which we sumptuously regaled.” Nicolas Baudin stopped at the same reef in 1803, and he too had a feast (probably with a glass of decent champers, being French and all).

For the early settlers of South Australia, the oysters were not only a valuable food source, but also a taste of home. Ostrea angasi is a very similar oyster to Ostrea edulis, the shellfish that settlers were very familiar with.

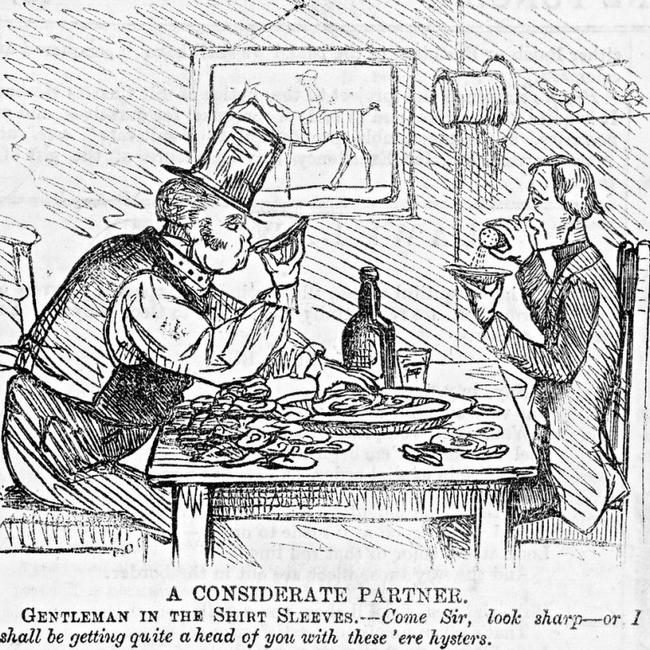

Back in the British Isles shellfish were a favourite food of the working classes, consumed in great numbers — and washed down with plenty of beer — in oyster saloons. They were also sold on the street by mobile vendors, made famous in the song Molly Malone.

So to find the same food here on the other side of the world, where black swans and hopping kangaroos created an entirely alien environment, must have been comforting.

Over in Coffin Bay, a town still famous today for oyster farming, tonnes of shellfish were being dredged for the Adelaide market by the mid 1840s. By 1849 there were up to thirty cutters working the waters off Oyster Town, as the settlement became known, with the shellfish being hauled by bullock wagon back to Port Lincoln and then shipped by ketch to Port Adelaide to feed the city dwellers. The oysters were laid down in the Port River and in the Glenelg area, and kept alive until they were needed to supply the many oyster saloons that had sprung up around the city.

That’s if the thieves didn’t get to them first.

“I have the honour to request you to inform me if I have any legal means of preventing persons from pillaging beds of oysters which I form on the coast near Glenelg,” a Mr Hansford Ward wrote to the colonial secretary in 1850, complaining of “unscrupulous persons who watch me while I form beds of oysters and when my back is turned proceed to immediately rob me”.

There are many reports from the time of people facing court in Adelaide for helping themselves to a feed of someone else’s oysters. Oyster Bay was fished out by the 1880s, but plenty of cutters were working other areas of the Eyre and Yorke peninsulas. The seafood may not have yet gained its later reputation as an aphrodisiac, but it was certainly seen as an early superfood.

“To a man at all fatigued oysters and stout are a wonderful reviver,” one newspaper columnist wrote, and a report from The Advertiser in 1870 attested to their popularity; “As long as the national taste for oysters continues, there will remain that everlasting noisy oysterman with basket and knife ready at 11pm to administer to admirers of the briny morsel.”

Inside the oyster saloons, life was rough. Think about the dodgiest front bar you’ve ever been in, then double. National news reports abound of drunken fights, stabbings, smashed windows, theft and prostitution.

These were definitely not high-class establishments.

Many of the oyster bars were, technically, unlicensed — but the booze, and the subsequent violence, flowed freely.

A letter writer to the Register in 1869 wrote: “Sir, as a stranger in Adelaide, I beg to ask how it is that oysters can hardly be enjoyed here except among dirt and vice …”

Dirt and vice, however, turned out to be the least of the oyster eater’s worries. By the early 1900s the water in the Port River had become so dirty that the oysters had, according to news reports, been infected with typhoid.

“A TYPHOID OUTBREAK” screamed the front page headline in The Port Adelaide News in 1916.

Then, in case anyone missed it, two subheads: “A pestiferous canal” and “Disease laden oysters”.

Things were looking bad for oysters in the Port River, and it wasn’t long before storing them in the waterway would be banned forever. The oyster boom, it seemed, was over.

Now, thanks to the hard work of the Estuary Care Foundation, founded by Catherine McMahon, native oysters are back in the Port River — although these ones are not for eating.

“We’ve been working on restoring the oysters to the river,” Ms McMahon said.

“We put adult oysters in back in May of 2017 across six sites and they’ve gone really well. Our most recent project was to create a small reef in the Inner Harbor and seed that with oysters and that’s also been very successful.

An adult oyster can filter a bathtub of water every day, so they’re really important as a filter feeder.” Ms McMahon said the Port River was much healthier system than it had been in decades gone by.

“We also wanted to demonstrate the improved health of the Port River and one way of doing that was bringing back this Aussie battler,” she said.

“It actually is a living system. We want people to come and swim and paddleboard and kayak in the river.”

Estuary Care Foundation is hosting two Port Oyster Tales and Bubbles events as part of the history festival. Hear talks and compare the taste of native and Pacific oysters, all washed down with a glass of champagne. To book for the May 16 and June 1 events go to historyfestival.sa.gov.au