*This was originally published in August 2018.

It’s a boon waiting to happen — or is it? It depends on who you ask.

The Great Australian Bight is rich in marine life, but also, potentially, in oil and gas deposits … so is there a way to balance these considerations for the betterment of South Australia?

In the follow-up to the August announcement that development could create up to 1500 jobs plus billions in annual tax revenue, The Advertiser has taken a deep-dive into this complex issue, examining the region as an ecological marvel but also an area of economic potential.

And like the area, it isn’t a small issue.

The Bight covers a shoreline of 1160km from Cape Pasley in Western Australia to Cape Carnot and includes the jewel of South Australia’s eco-tourism crown: Kangaroo Island.

Yet it is also an area ripe with oil and gas development opportunities.

So where do we go from here? You’ll have the chance to have your say at the end of this article as we explain the issue, its stakeholders and what comes next.

THE $175 BILLION QUESTION

The production of oil and gas in the Great Australian Bight would provide an economic boon for South Australia — in fact, it would match the 50-year stimulus by Bass Strait fields to southeastern Australia … at least according to the state’s chief industry representative.

Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association (APPEA) state director Matthew Doman has said drilling in The Bight was “the big opportunity” for the oil and gas sector in South Australia, suggesting its potential benefits remained largely unknown.

“The industry believes that the resources in the Great Australian Bight could be comfortably equivalent or greater than those in Bass Strait, which has contributed very significantly to the economic strength of Victoria and Tasmania for many years since production began there in the 1960s,” he said.

So if that were to come to pass we would see a very significant stimulus towards SA’s economic growth.

“There is no doubt that in the recent public discussion, there hasn’t been a clear focus on the economic benefits or the energy benefits of developing those resources.”

According to consultants ACIL Allen, the Gippsland Basin Joint Venture — by far the biggest producer in Bass Strait — produced 4.7 billion barrels of oil in that area from 1967 to 2015, and 8 trillion cubic feet of gas.

In that time, it generated gross revenue of more than $144 billion and paid more than $89 billion in Australian excises, royalties and taxes.

In 2016, consultants Wood Mackenzie estimated the region contained a potential resource of 1.9 billion barrels of oil, worth close to $175 billion at current prices.

Mr Doman said the industry was committed to winning over community support despite fierce opposition led by local councils and environmental groups including the Wilderness Society.

“There’s a lot of people in those communities — in Port Lincoln, Ceduna and other areas — who are very supportive of our industry and see the opportunity for us to contribute alongside existing industries, to growing those regions,” he said.

“Of course it has to be done in an environmentally safe manner, we have to make sure there’s no negative impact on existing industries or coastal communities — we’re committed to doing that.

“And if you look at our industry around Australia, we haven’t seen negative impacts in the Bass Strait, we haven’t seen negative impacts in the North West Shelf — we’ve seen just the opposite.”

Mr Doman said the broader oil and gas industry needed to improve its response to “orchestrated, carefully planned and well-funded” campaigns from international environmental groups who opposed new developments.

“There has been a concerted campaign to scare and misinform the community over the impacts of our industry,” he said.

“Exaggerated claims of community opposition to our industry when there’s clear evidence of very close collaboration between us and farm owners, local businesses and the broader community.

“Most disturbingly, these campaigns do have an impact, and the grossly exaggerated claims of environmental contamination have been very hard for our industry to respond to — we need to do a better job of that.”

SEAL COVE — SO GOOD WE CAN’T EVEN TOUCH IT

The beach at Seal Cove is so exclusive that the hundreds of tourists who go there every year are not allowed to set foot on it.

Locals have the small patch of sand to themselves, but they’re not stuck up about it.

In fact, visitors arriving at otherwise rocky Hopkins Island by boat from Port Lincoln are likely to be met by a welcome party.

For Australian sea lions the beach is a sanctuary in a stormy South Australian ocean 32km southwest of the Eyre Peninsula’s biggest town.

Tourism operators take boatloads of people to the shallow cove so that they can swim with the inquisitive and playful mammals who rush out to meet them like loveable puppies, but that’s as close as anyone gets to a shoreline that’s just too sensitive to take any ecological chances.

When Greenpeace recently conducted a media tour of South Australian marine habitats it fears could be destroyed by oil exploration in the Great Australian Bight, it made Seal Cove the first stop and let that habitat speak for itself, the wide-eyed sea lions tugging at emotions as the obvious fragility of a wild coast stamped itself on the mind.

It was a pretty standard PR pitch by the world’s best-known, and most media-savvy, environmental organisation — but it didn’t go to plan.

The sea was rough when the charter boat left Port Lincoln long before dawn and even in the sheltered cove the swell was too great for anyone but experienced divers to join the sea lions in the water.

The next stop — far to the south at the Neptune Islands — included a dive in a shark cage, but the great whites didn’t show.

Then the journey home was made through storms and an angry sea, with a couple of dozen landlubbers tossed all over the place, as was a stomach or two.

No swimming, no sharks, little footage, few photos and a boatload of bruised and battered journos — if this had been a media tourism junket, it would have been a failure.

But it was neither.

Greenpeace wanted to show how vulnerable this ocean would be in the event of a major oil spill spreading from The Bight. While sea lions and sharks had been teed up as the talent, the ocean had spoken.

This is a wild, unpredictable place and if you don’t expect the unexpected, it can give you a nasty surprise.

BIGHT-SIZED OPPORTUNITIES

At an energy industry conference in Adelaide in 2018, Federal Resources Minister Matthew Canavan announced that more of The Bight had been opened up to oil and gas exploration.

The latest block of seabed about 190km off the coast and 820km from Adelaide has, according to him, “multiple potential oil-and-gas-prone source rocks’’.

The Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association was the right crowd for that news.

Outside the Adelaide Convention Centre, though, protesters were making known their opposition to drilling plans by Norwegian company Equinor.

The Federal Government has been issuing exploration leases in The Bight since 2011 and geologists are confident there’s oil and/or gas down there.

How much and exactly where is still unknown.

Energy giants BP and Chevron have already had a look and pulled out and Equinor is close to sinking The Bight’s first well, provided it can satisfy the safety requirements of the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority.

BP was unable to do this and, while it cited economics as its reason for retreating from The Bight, many believe it just found the regulatory hoops too difficult.

Those regulations have become much more demanding since BP’s 2010 Deepwater Horizon well disaster in the Gulf of Mexico.

Considered the worst spill in history, it poured 780,000 cubic metres of oil into the sea, took three months to control and years to clean up, The ecological consequences are still ongoing.

The worst-case scenario here could be as a bad as Deepwater Horizon — Emeritus Professor Andrew Hopkins on the Greenpeace tour.

The Australian National University academic is not a member of the organisation or an environmental activist, but was invited along as an expert in industrial risk.

“You can never eliminate risks,” he told The Advertiser.

“All you can do is manage them to the best of your ability. That management means resources and time and commitment and, over time, those resources can get withdrawn from an enterprise under constant pressure to cut costs and to drill more quickly.

“Safeguards against major accidents tend to be whittled away over time. The constant background is this relentless pressure to drill as fast as you can.

“It’s relentless because these companies set up bonus arrangements for all their employees and one of the components is how fast you are drilling. The faster you drill, the bigger your bonus.

“This is the pressure to ignore things that might not be right and get on with your job, and therein lies the problem.”

GORN’ FISHING

Environmental groups and safety experts are not the only people concerned at the prospect of a Bight oil accident.

The multibillion-dollar tuna industry is ideologically in favour of safe and sustainable harvesting of natural resources. It just doesn’t believe oil companies will be able to do that in the wild waters of The Bight.

“None of the companies … have agreed to the mitigation or safeguard measures which are necessary to make it a safe proposition,” says Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association chief executive officer Brian Jeffries.

He has been impressed with Equinor’s “no-bullshit” approach to dealing with concerns, but “I don’t think they quite realise, as expert as they are, just how difficult those conditions are out there”.

“The best fishermen in the world, the Japanese tuna longliners, say it’s just impossible out there to fish, let alone run safely a rig like that,” he says.

“A lot of companies around the world are drilling in quite benign waters … I don’t think they understand the conditions in The Bight. Summer or winter, it’s probably the roughest waters in the world.”

REAL-TIME SWELL IN THE BIGHT — CLICK TO DISCOVER MORE

Mr Jeffries also believes oil companies, when planning how to make amends if things do go wrong, don’t understand the tuna quota system, which was not in place in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

Through the safeguard against overfishing, fishers pay thousands of dollars to take certain tonnages and many borrow to cover this.

It’s a major expense.

“Oil companies tend to think of compensation as a one or two-year thing. But if we lose that quota for 10 years — or whatever it takes to regain the stock — then that’s a massive loss that far exceeds the Deepwater Horizon incident,” Mr Jeffries says.

“You’re not talking about a fishery that’s closed for a year and you pay a few people out. We are talking about a decade of lower quota or no quota. If you have no quota, you’ve still got to pay the bank back.”

Such a situation would devastate Port Lincoln, Mr Jeffries says.

“It’s the economic heart and soul of Eyre Peninsula … you just walk away, and once you walk away from operations like this, you tend to not come back.”

Equinor says it can afford to compensate industries affected by any spill, but that its four decades of drilling experience should give Australians confidence that won’t happen.

“We are committed to protecting our people and the environment. In the highly unlikely event there is a spill, the mechanical response will be immediate — we will act to stop and contain any hydrocarbon release,” says Jacques-Etienne Michel, Equinor’s manager in Australia.

“Our response measures will act to prevent any oil reaching shore, which is 400km away.”

Equinor acknowledges the Greens are trying to have The Bight listed as a World Heritage Site that would be protected from drilling and “we will not challenge the application”.

“We aim to work collaboratively with conservation groups in the Great Australian Bight,” Mr Michel says.

WHERE DO THE COUNCILS STAND?

At the community level, eleven SA councils are opposed to or concerned by drilling plans — plus one from Victoria.

The SA councils so far expressing concerns about the plans represent 540,000 people: Port Adelaide Enfield, Kangaroo Island, Victor Harbor, Yorke Peninsula, Onkaparinga, Yankalilla, Holdfast Bay, Marion, West Torrens, Elliston, and Alexandrina.

Moyne Council, based in the heritage town of Port Fairy on the Great Ocean Road in Victoria, has voted to become part of negotiations about the prospect of oil drilling being investigated by Equinor.

The Norwegian company is applying for permission to drill in the central area of The Bight but green groups are opposed to any exploration.

Moyne Council has passed a resolution stating: “Moyne Shire Council acknowledges concerns regarding deep sea oil drilling in the Great Australian Bight and commits to writing to Equinor and the relevant federal minister to request full consultation from Equinor in relation to the development of its proposed Environmental Plan’’.

A notable exception from councils expressing concern is Port Lincoln — but a motion is under consideration.

Equinor’s AGM in Norway was attended by Kangaroo Island mayor Peter Clements, who told the company that it should “quit its plans to drill in the deep, rough and remote waters of the Great Australian Bight, just as BP and Chevron have already done”.

In an opinion piece in The Advertiser, Mr Clements pointed out that “incredibly, this week, the Southern Ocean recorded wave heights of 23m (equivalent to an eight-storey building)”.

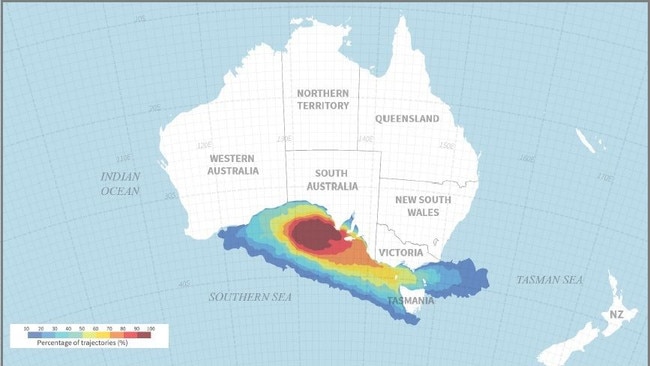

“The Great Australian Bight waters are deeper, more treacherous and more remote than the Gulf of Mexico”, he wrote, adding that BP’s own oil spill modelling showed a slick from an ultra-deepwater well blowout could have an impact “anywhere along all of southern Australia’s coast”.

Independent modelling shows much the same thing.

“A spill could hit Adelaide in 20 days and could hit Port Lincoln and Kangaroo Island in 15 days,” Mr Clements said.

But oil-slicked birds, dead wildlife and blackened beaches in the horrifying Deepwater Horizon images of 2010 won’t have to be replicated here to constitute an ecological disaster, says Dr Jodie Rummer, an Australian Research Council researcher at James Cook University who was also invited on the Greenpeace trip.

The reef ecology specialist says that a dissipated spill and the equivalent of “just a few drops in an Olympic swimming pool” would be invisible, but deadly.

“Even if we think the concentrations are really, really low — not enough to cause a massive fish kill — fish could be cognitively impaired or physiologically impaired in terms of their cardiac function, their circulatory systems, their musculature,” she says.

“These are all things we have found that have resulted from a study using the examples from Deepwater Horizon.”

THE SOCIAL CAMPAIGN

The Greenpeace’s campaign against Bight drilling also recruited scientific star power in marine biologist and fashion model Laura Wells and world-rated freediver Julia Wheeler, who is also a nature photographer.

In the age of the social-media influencer, they have more than 170,000 Instagram followers between them and have been using the platform to oppose drilling.

They also joined the boat tour with winners of an essay competition run by the environmental group.

One of the winners, surfer Jamilla Martin, 19, of Adelaide, said drilling in The Bight would be “crazy and ridiculous, just a stupid idea”.

“If there is a spill, cleaning it up is going to be next to impossible,” she says.

Greenpeace campaigner Nathaniel Pelle says the community and industries that rely on the Great Australian Bight “have already turned away two of the world’s biggest oil companies in BP and Chevron” and that the environmental group would continue a fight it expects to win.

“The oil industry is flailing, caught between low oil prices, the electric-vehicle revolution, new climate laws and communities who don’t want a Gulf of Mexico spill in their backyard,” he says.

SO WHAT’S NEXT?

Equinor plans to commence drilling in The Bight at the end of next year, after energy giants BP and Chevron shelved their plans in 2016 and 2017.

Other companies including Karoon Oil, Bight Petroleum and Murphy Oil also hold exploration permits in the area.

But while the oil giant has plans for 2019, in April the federal National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority ruled it was not yet satisfied that seismic testing plans within the Duntroon Basin, which are not owned by Equinor but are among the closest to KI, were safe for the environment and proposals would have to be resubmitted.

APPEA’s Matthew Doman said testing in The Bight for oil and gas would only proceed with the highest environmental safety standards.

“The benefits of successful exploration will be significant for South Australia, and the industry accepts and will respond to the questions and concerns of the community,’’ he said.

“It would only go ahead after rigorous approval and community consultation.’’

YOU’VE GOT THIS FAR — WELL DONE! FINALLY, HAVE YOUR SAY

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout