Family remembers little Chloe Valentine ahead of what would have been her 10th birthday

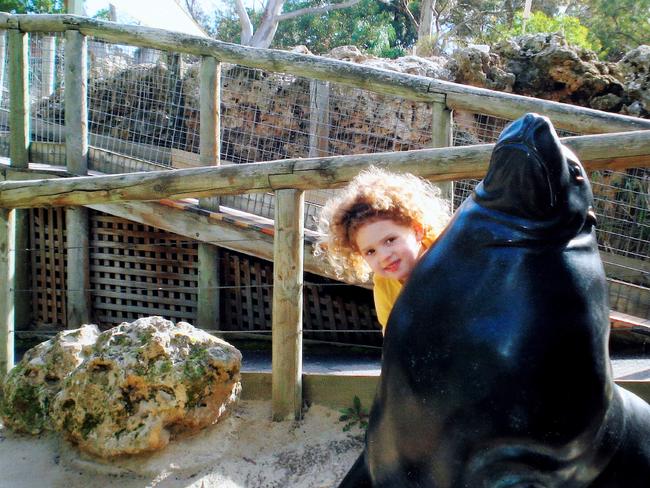

CHLOE Lee Valentine should be celebrating her 10th birthday this Thursday. Instead, she will remain “forever four” in the memories of her relatives, who know their sweet dragonfly left an extraordinary legacy.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- SA Government introduces “Chloe’s Law” to Parliament

- Parliament passes Chloe’s Law a year after coronial inquest findings delivered.

- More drug tests for parents of at-risk children

- Lauren Novak: Parents must care better for their children so social workers can focus on serious abuse

ON little Chloe Lee Valentine’s birthday, her family would usually celebrate by spending the day in their pyjamas, eating fruity pavlova and watching Disney princess movies.

On Thursday, she would have turned 10 — a milestone birthday for any child.

The blonde-haired, brown-eyed little girl probably would have worn a princess dress, maybe inspired by the characters in the hit film Frozen, and eaten lollipops and lots of cheese — she loved cheese.

But Chloe never reached her fifth birthday, let alone her 10th. Instead, she died at the age of four, held in the arms of her grandmother in an intensive care ward at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

Chloe’s mother, Ashlee Polkinghorne, will spend what would have been her daughter’s 10th birthday in jail — along with the man she was then living with, Ben McPartland — for allowing her to die from massive injuries caused at their home in January 2012.

Many will remember the uncomfortable footage of Chloe continually crashing a motorbike, much too large for her, in the couple’s backyard until she crashed into a lemon tree and, later that night, stopped breathing.

Ashlee, then 20, had a history of drug-taking and Chloe had been the subject of numerous reports to child welfare authorities.

The case horrified South Australians but it also spurred them to demand changes so that no other child would suffer the same fate.

A coronial inquest and a royal commission followed, sparking changes to the law and a complete overhaul of the Department for Child Protection.

The result is Chloe’s legacy and it keeps her family going as they feel her painful absence this week.

“She was very funny. She had this tinkling little laugh and she loved sweet things,” Chloe’s grandmother, Belinda Valentine, 50, remembers.

“She could also be stubborn and she had this great scowly face that she would give you if she didn’t want to do something. She went through horrible stuff but she was a strong kid.

“She was special. She wasn’t an angel, but she was perfect to us.”

Chloe’s young uncles — brothers to Ashlee — have also spoken publicly for the first time about their memories of the little girl who will forever be four years old to them.

“We were besties,” says 13-year-old Chad, whose birthday falls less than a fortnight before Chloe’s.

“We did face-painting together. And she loved snakes — she wasn’t scared of them.

“I still say ‘Good morning’ to her every day but it’s hard because sometimes I feel like she doesn’t answer,” the young man adds, tears rolling down his cheeks.

Ms Valentine says her youngest son and her granddaughter were like “two peas in a pod”.

“Chad would play fairies and princesses with her and then she’d do zombies and war games with him,” Ms Valentine recalls with a smile. “Because they were so similar in age, they were sort of like twins and Chad would call her his secret little sister.”

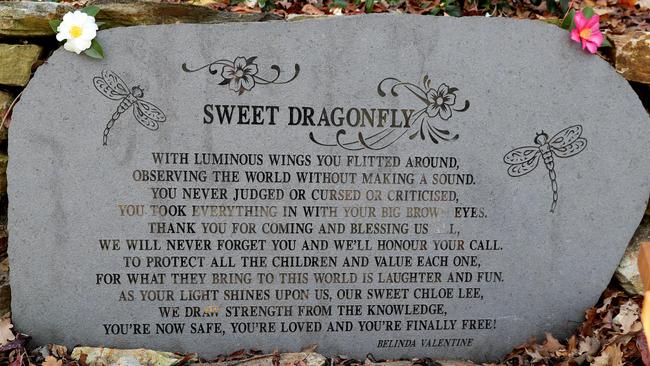

The pair often played at a public park not far from home, where they would splash in a creek. The family have since arranged to place a large stone at that same park, in the Adelaide Hills, engraved with a poem about Chloe written by Ms Valentine.

Her older son, Scott, now 16, says: “She’s still my niece and I love her.

“I don’t see her as ever being 10 years old. I see her as being this four-year-old girl who will be four forever.

“But if she grew up, she definitely would have been an athlete. She was faster than me even back then. And she would be doing well at school.”

Scott also remembers a cheeky side to his young niece.

“She loved cheese and she would refuse to eat any vegetables until I smothered them in cheese for her,” he laughs. Chad chimes in that sometimes Chloe would “lick the cheese off so we would have to put more on for her”.

Ms Valentine recalls Chloe “pinching cheese slices from the fridge” and a fondness for sweets which earned her the nickname “lollipop”.

Chloe was born on July 13, 2007, to then 16-year-old Ashlee and young dad Tom Langdon, who later moved to Perth.

Ashlee had left home at a young age and, after splitting from Langdon, she and Chloe lived in several different homes. There were times when things seemed relatively good, almost normal.

But most of the time Chloe lived in a world of risk, neglect and violence and was exposed to drug-taking by her young mother and her friends.

Ms Valentine and her husband, Steve Harvey, who is not Ashlee’s father, say they tried to help but were often shut out by Ashlee and child protection authorities. To this day, they are approached by complete strangers asking “Why didn’t you save Chloe?”.

“People don’t understand that comments they make based on insinuations like that are really painful,” Ms Valentine says.

“We still have people say to us now ‘You were the grandparents, you knew what was going on, you should have just taken her away’.

“The fact of the matter is we were trying to do that but we’d been warned by the police, by the Child Protection Department` that ‘If you go in and take her away, you will never see that child again because you’ve gone in and done something that’s against the law’.

“That would have become the focal point of the case, rather than the fact that the child was in danger.” Mr Harvey, 58, added that his wife was “on the phone almost every second day” to child protection workers about Ashlee and Chloe.

“What do you do? If you take her (Chloe), then she (Ashlee) will send the police after you and we had two other young children at home (Scott and Chad) to consider, which people don’t realise,” he says.

“We were told (by Child Protection workers) they might consider giving us Chloe but we had to take Ashlee, too. We couldn’t do that — bring a toxic, drug-addicted person into our family home. Our kids would have been in peril as well.”

Despite the chaos, Ms Valentine says they “had no idea that it was going to end like this”.

“Hindsight’s a terrible thing. We have to live with that but we also live with a certain level of confidence that we did do everything we could in the circumstances.”

The day Chloe died is as fresh in Ms Valentine’s memory — and as painful — as it was more than five years ago. It was January 20, 2012. She and Mr Harvey were in Sydney, teaching a face-painting course as part of their family business.

“It was a nice sunny day, everything was lovely, there was glitter everywhere,” Ms Valentine remembers.

“About 11am, I get this phone call from Ashlee and it was so mumbled. Then, all of a sudden, I hear ‘They think she’s brain-dead’.

“I just remember saying to her ‘What are you talking about?’. I remember everything stopping.

“She just said ‘They think that Chloe’s brain-dead’.

“I think I nearly collapsed. Everything came in on me.”

While Ms Valentine had been in Sydney, Chloe had suffered massive injuries at home in Ingle Farm and had eventually been taken to the Women’s and Children’s Hospital with severe brain damage. It was only then — hours after Chloe was admitted — that Ashlee rang her mother.

“I spoke with the doctor on the phone and he said ‘You need to get back here now’,” Ms Valentine says.

The next few hours were a blur — being put in a taxi, arriving at Sydney Airport, being rushed through to the only remaining seat on the next flight back to Adelaide. “Sometimes when I’m flying back from Sydney that’s hard for me, having those feelings again,” Ms Valentine says of the terrible journey home.

Arriving at the hospital, she was warned by her eldest son, Jake, now 29, to ‘prepare yourself Mum. Chloe looks really bad’.

“I couldn’t even recognise her,” Ms Valentine whispers, remembering her first glimpse of her battered granddaughter on a hospital bed that day.

“I thought, that’s not Chloe, they’ve made a mistake. And then it hits you that it is her. It was sickening.

“The sheet was up to her chin. I needed to see her so I took the sheet off and she was so broken. She was just totally broken and bruised. I thought, ‘What have they done to her?

“Those pictures are still in my mind. I don’t want anyone else to ever have to go through that.”

The doctors explained that Chloe’s brain was no longer receiving oxygen and delivered the devastating news that she could not be saved.

Ashlee was at the hospital and held her child in those final hours but she struggled with the emotional weight of the life-shattering moment and left before Chloe died. Ms Valentine was left holding her granddaughter in her arms after doctors switched off her life support.

“They turned the lights down really low. We were just talking to her, saying ‘We love you, we’re so sorry, we wish we could have done something else’,” she remembers.

“The doctors came in saying her heart is slowing down now, she’s going to pass away soon, and I just remember thinking ‘Not now, I’m not ready. I just need more time’,” Ms Valentine says, her voice cracking as she relives the panic of that moment.

“Then she died … and I remember thinking ‘How is this happening in my life, in my family?’.”

Reflecting on that day now, Ms Valentine struggles to find the words to describe her grief.

“You can’t even explain the feelings. The words feel disrespectful because it’s only a droplet in the ocean. It doesn’t explain the depth of emotion,” she says, exasperated.

“None of us realise how much you love someone until you lose them.”

When she returned home from the hospital, Ms Valentine had the awful job of telling her young sons, who were 7 and 11 at the time.

“I was shattered,” says Chad. “I couldn’t sleep. I was really sad.”

Scott says he tried to block out the grief: “I sort of just switched off. I didn’t want to feel anything”.

“But I don’t get as emotional anymore. It’s not as hard for me to talk about anymore. I know Chloe wouldn’t want us to sit around and grieve her forever. She’d want us to go out and have fun and help other little girls have fun.”

For Ms Valentine, the focus now is turning to the future.

“We thought we were just a normal, average family. But this is our new normal,” she says. “The pain never goes; you just make room within yourself.

“It’s really hard when there’s been trauma to pull out the positive stuff. Part of doing that is by asking ‘What are the lessons? What did we learn from this?’

“It’s a hard, messy journey but there is hope. Each person who tells us their positive story of change in their lives, with their children, because of our story — that brings us a lot of hope.

“Anyone who loses a child knows that child is extraordinarily important. The important awareness for change that’s happened because of (the loss of Chloe) is huge and we’re so grateful for that.”

Changes for the better include new laws which empower authorities to remove a child automatically at birth from any parent convicted of murder, manslaughter, causing serious harm to or endangering the life of a child.

The agency responsible for child safety when Chloe was alive, Families SA, has been overhauled and renamed the Child Protection Department.

It has a new boss, Cathy Taylor, and is working to implement changes recommended by Coroner Mark Johns’ inquest into Chloe’s death and a later royal commission into the wider child-protection system.

Other legislation, which passed Parliament during the week, will enshrine in law that keeping children safe from harm should be the most important factor in making decisions regarding child protection.

However, Mr Harvey notes that while the upper ranks of the system have changed, many of the same workers remain on the frontline and are face the same issues. He believes there is still a lot more to be done.

Putting themselves in front of cameras and advocating publicly for change has taken a toll on the family, but they say they will continue to bear it if it means others don’t have to live through a preventable tragedy.

These days, the family honours Chloe — and creates new memories — through their face-painting business, travelling around the country putting smiles on the faces of young children.

Ms Valentine is reminded of her granddaughter every time she sits down to paint the cherubic face of a little girl with golden curls.

It was at the first Royal Show they attended after Chloe’s death that a surprise visitor gave she and Mr Harvey a little hope.

“It was in Melbourne, at the end of winter, after we set up our tent and we looked up in the corner and there was this dragonfly sitting, watching us” Mr Harvey remembers. “It stayed there for the whole Show.”

The insect holds special significance, as Ms Valentine explains.

“When Chloe was at our house one day, she came walking in the back door with this big dragonfly sitting on her hand,” she recalls. “She said ‘Look, nanna’, and put out her hand to say ‘You can hold it’.

“It jumped onto my hand but then it buzzed away. Chloe just said ‘It’s OK’ and put her hand out and the dragonfly came back to her. Then she walked to the door and let it fly away.

“It was amazing. I remember thinking ‘Who is this child?’.

“Later I found Chloe sitting on a stool looking thoughtful. She said ‘That must have been a really special dragonfly to come and land on me’.

“I looked at her and thought ‘No, actually Chloe, I think you’re the special one’.”