Deutsch courage: Push to keep Barossa language alive

STROLL the streets of the Barossa Valley 100 years ago and you would have been as likely to receive a guten morgen as a good morning — now it’s a fight to keep the Barossa Deutsch language alive.

STROLL the streets of the Barossa Valley 100 years ago and you would have been as likely to receive a guten morgen as a good morning.

The area, famously settled by hardworking German immigrants in the mid-1800s, was a hotbed of German language – a language that gradually took on elements of English vocabulary and grammar and became known Barossa Deutsch.

Barossa Deutsch was the first language of many prominent South Australians, including Storm Boy author Colin Thiele, but these days the number of speakers is dwindling.

However if enthusiasts like University of Adelaide Visiting Research Fellow Peter Mickan get their way, the streets of the famous wine growing region will once again ring with the sound of Teutonic conversation.

Dr Mickan is one of the driving forces behind a number of programs aimed at keeping older, native speakers of Barossa Deutsch conversing and passing on the language to a new generation.

Monthly Kaffe und Kuchen (coffee and cake) meetings, visits to aged care homes (where many native speakers now reside) and even German playgroups are just some of the initiatives in place.

“There were 52 bi-lingual schools in South Australia that taught in German in the morning and English in the afternoon,” Dr Mickan said.

“We call it Barossa Deutsch, but it was spoken beyond the Barossa Valley. The Adelaide Hills, Yorke Peninsula and the South-East all had German-speaking populations.

“The interesting thing about the Barossa is that it became a language island, a sprachinsel. This was German with an English influence on the vocabulary and grammar.”

Dr Mickan said anti-German sentiment around the time of both world wars meant that speaking Barossa Deutsch in public could be frowned upon.

“One story I’ve heard was from a German speaker whose classmates asked him to teach them the numbers in German,” he said. “When the teacher found out he was punished – that was the general feeling around speaking German.”

Dr Mickan said a particularly satisfying part of recent efforts to keep the language alive was seeing people in aged care speak German again for the first time in decades.

“The Lutheran services and the church hymns were all in German when they were young, and they were craving a chance to speak German again,” he said.

“In one Tanunda home alone there were 27 residents who grew up with German as their first language. Now we have a Barossa German Inc. that does visits to homes for the elderly in the Barossa. These are monthly get-togethers, with some people who are more than 100 years old, to sing German songs and listen to their stories.

“As you age it’s very important to have that exposure to your first language … just to see the tears in their eyes when they hear their Confirmation hymn in the language they grew up with.”

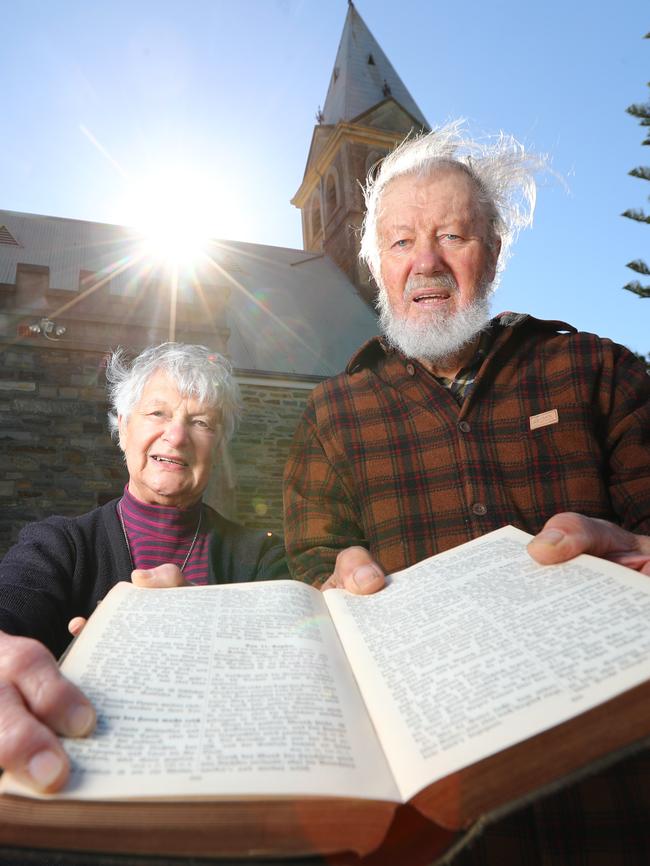

Don Ross and Marie Heinrich both grew up speaking Barossa Deutsch at home, although unlike some older Barossa residents they both knew English by the time they started school.

“I learned it from my parents and grandparents,” Mr Ross said.

“I learned German and then English, but some children started school with no English at all and that must have been difficult.”

Mr Ross, who is 80, said he and Mrs Heinrich were among the last generation for whom German was the first language.

Mrs Heinrich said her own children weren’t fluent German speakers.

“As if often the case, they mainly know the words that you shouldn’t say,” she laughed.

Dr Mickan will be speaking at the Conference of German-Australian History and Heritage, to be held at Adelaide University from August 17 to 19. Visit germanheritage.org.au