D-Day Veteran Charles Oram recalls his remarkable tale of survival at Normandy in 1944

75 years after the D-Day landings, Craig Cook talks to one of the men who lived to tell the tale of how the Allies liberated Europe from the Nazis.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Charles Oram remembers D-Day as the day he dodged a bullet.

It was 75 years ago, on June 6, 1944, when the then 20-year-old with the Royal Marines was part of the largest seaborne invasion in history that changed the course of World War II.

D-Day, codenamed Operation Neptune, involved more than 150,000 Allied troops who stormed the Normandy beaches and triggered the liberation of German-occupied northwestern Europe from Nazi control.

Charles, a coxswain sergeant, was one of the busiest men on the seas, in charge of landing craft shuttling troops to the shore on the north coast of France.

With remarkable recall, the Rostrevor resident, who has spent 64 years in Australia, remembers the mayhem and the dramatic incident that almost claimed his life.

On one trip in, Charles’ troop carrier with 35 men on board got muscled out by a bigger craft carrying trucks and tanks.

He made the wise decision to give way.

“The Germans had laid an ingenious barrage of anti-landing devices along the coast designed to explode when a craft came up the beach,” he says in his clear London accent.

“Most were under water and couldn’t be seen.

“This large craft came up on my right and I yelled out, ‘Go on then, take my place mate’, when there was this massive bang.

“They got what was meant for me. I was just lucky I guess. You had to be lucky to survive.”

Four times Charles headed out with his load of troops and returned to pick up more.

“Put on your steel helmet and keep your head down was the drill,” he says.

“You don’t think about anything else than doing your job.

“We had orders not to stop for anyone … just keep ploughing on until you hit the shore.

“Rescue craft were supposedly coming up behind picking out the dead and injured from the water.”

Charles lost no mates that day but saw hundreds of bodies on the beach.

The invasion had been meticulously planned over months to be a day earlier, June 5, but foul weather in the English Channel caused a delay.

“We went over but it was too rough to land and we had to come back into Southampton,” Charles says.

“We went out again early the next morning but were never told precisely where we were headed and what it was all about.

“We had aerial photographs in a book of the area but we had no idea what beach we were landing on. The best sight I saw on D-Day was the (Allied) aeroplanes coming overhead and bombing the German forces on the shore, because they knew we were coming and had been picking off the landing craft.

“The operation took a few weeks and each night we’d head back to Southampton and then the Doodlebugs (V1 Pilotless bombers) would come over. You never felt safe.”

Australian sailors, soldiers and airmen were involved in D-Day but in limited numbers compared to other conflicts across Europe.

The main contribution came from about 2500 Australians who were serving in Royal Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force squadrons.

A further 500 Australian sailors served on Royal Navy vessels and a dozen Australian soldiers were attached to British army formations to gain experience in preparation for amphibious operations planned for the Pacific.

There were 14 Australian casualties on D-Day, including two sailors and 12 airmen.

Many other Australian airmen lost their lives in operations during the lead-up to the invasion and in the days that followed.

On both sides, more than 20,000 troops didn’t return home.

Charles isn’t one for ceremony and won’t be attending any commemoration of D-Day – not that there is one in Adelaide as the number of veterans are down to just a handful.

The respect for those who launched the invasion that ultimately saw the capitulation of Nazi Germany is being felt around the world.

Adelaide brothers Dino and Elio Centofanti and their friend Maurizio Di Lorenzo have made the journey to France.

“We are visiting the towns and beaches that were pivotal in the success of the Allies that led to the defeat of the Germans,” Dino, from Burnside, said.

“It’s been especially interesting to follow the footsteps of Easy Company, which were made famous in the Band of Brothers television series.”

The trio will attend the official D-Day ceremony at the American cemetery at Omaha Beach, near Cherbourg, along with international dignitaries.

Making a crust in SA was no pie in the sky for Charles

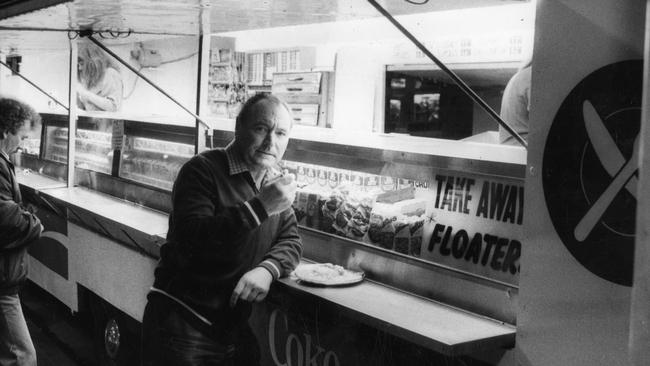

Charles Oram has a warm place in the hearts of South Australians as the long-time owner of the Adelaide Pie Cart on North Tce.

Charles was renowned for dishing up the famous pie floaters for 20 years opposite the Adelaide railway station

Within weeks of the D-Day operation Charles was sent out to the Pacific to train troops fighting the Japanese and had his 21st birthday on Bougainville Island. At the end of the war, he headed back to London, married his sweetheart Sylvia, and settled back to his trade as baker.

When the couple with two daughters immigrated to Australia as “10 pound Poms” in 1955, where a third child, a son, was born, Charles started his own baking business.

“I opened a cake shop (Oven Door Bakery) on Magill Rd in front of Otto’s – and next I built a bakery on Barnett Ave at Glynde that’s still there,” he says. His empire expanded to three bakeries across the eastern suburbs before the opportunity came to buy the pie cart in 1968 that was then situated on the corner of Rundle and King William streets.

The North Tce pie cart site outside the railway station had been popular since the early 1900s when visitors included the state’s 24th premier Tom Price, who would pop over from Parliament House for a regular feed.

But when Charlie transferred his business there in October 1970 there hadn’t been a pie cart outside the station for nearly 30 years.

It quickly became an Adelaide landmark and a novel tourist attraction for interstate and international visitors.

Charlie had his battles with the Adelaide City Council, raised regularly in State Parliament, that refused several times to extend his licensing hours.

In 1982 he spent $1000 hiring private investigators in a bid to prove noise complaints about the pie cart were unjustified before finally, in 1986, he won an all-night trading licence from 6pm to 6am.

“We had good business through the night … casino staff and patrons, police, office cleaners, railway workers, and those who worked at the Festival Theatre including the stars,” he says.

“The pie floater was always my bestseller.”

But less than a year later Charles sold the business for an undisclosed figure telling The Advertiser he wanted to “spend more time with my family and on the golf course.”

“I sold the pie cart to Balfour’s – and they buggered the business up,” he adds with a cheeky grin.

After living independently, he only moved into the ACH Milpara nursing home at Rostrevor two years ago.

“It’s been a good life – with no regrets,” he says.

“I’ve been very lucky and I know it.”