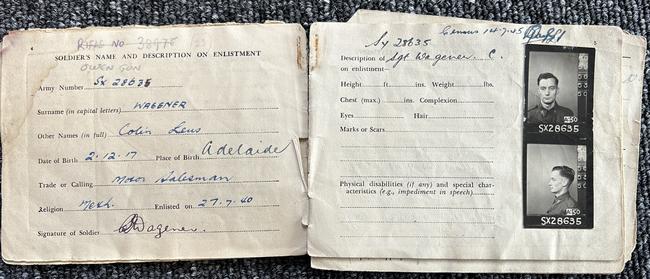

Colin Wagener, who at 106 is SA’s oldest WWII veteran, reflects on his life in profound and moving interview

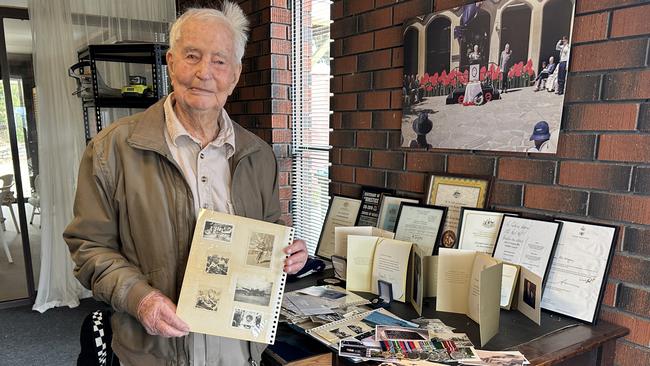

Colin Wagener had a front-row seat to history during WWII. But for decades the 106-year-old couldn’t bring himself to talk about it. Read our extraordinary interview with SA’s oldest veteran.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For six and a half decades, Adelaide Hills centenarian Colin Wagener didn’t speak – and tried not to think – about World War II.

The medals he’d received, which included the Pacific Star and Efficiency Medal for “loyalty and dedication to safeguarding Australia and its interests”, sat untouched, hidden away in boxes.

“I’d had a gutsful”, the straight-talking 106-year-old says.

“Before the war, I used to see the WWI boys marching and they’d have two, sometimes three medals, and I’d think how wonderful it would be to wear medals … when I finally got them, I didn’t want them.

“I didn’t want to know about (the war); you were in a tent with eight people week after week, month after month and you’d had a gutsful.

“Every time you had a shower, you had to take your gun with you; your meals were a tin with grey matter – cold stew – in it.

“I just wanted to get home but there was nothing you could do about it. I thought the war would never end and that I would be in the army for the rest of my life and then suddenly … it all stopped.

“They tell me I have PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) … all my life (since) I have been taking sleeping tablets, I can’t do without them.

“I was lucky, I was well off all the way through and didn’t even get shot; I didn’t have the rough and tumble of POW camps like so many others.”

Of the three South Australian mates he enlisted with just he and one other made it home.

“We were mad, we must have been mad,” he says.

Asked if was afraid of dying, he pauses and considers the question before answering.

“I don’t think I was … I don’t think people think along those lines; we looked at it the other way around, we wanted to live, we didn’t want to die (but) we didn’t know how close we’d get at times,” he says.

“War hardens you. (There comes a point) you no longer give a damn; you become conditioned – if someone is waiting out in the jungle and you are killed, too bad, if you had to eat a meal you didn’t like, it didn’t matter … you had no choice.”

Mr Wagener says words he read on a visit to the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery in Thailand many, many years after the war ended, have remained with him.

“‘When you go home, tell them that we gave our tomorrow for your today’ … that is powerful, that one,” he says.

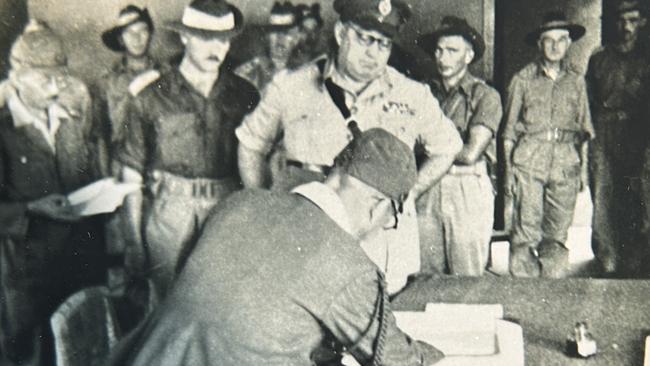

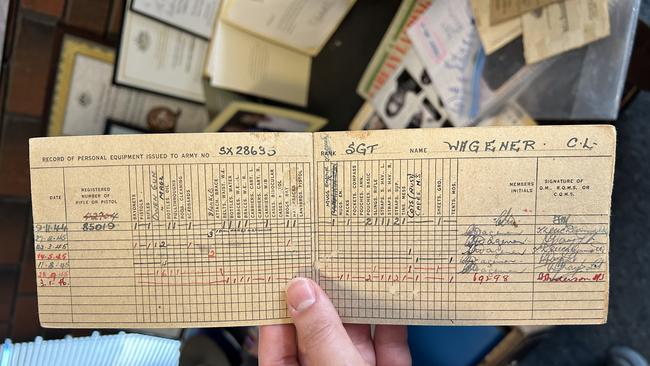

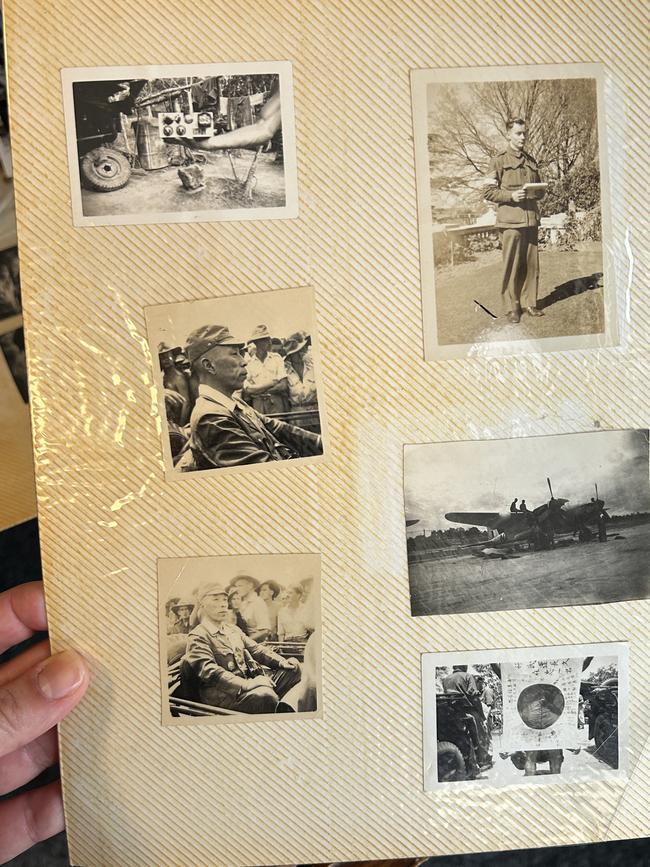

Mr Wagener, who was in the signals unit – responsible for “telling them when to start firing or turn on the searchlights” – with the 2/3rd anti-aircraft AA regiment (9th division) in Borneo, was there when Japanese war criminal Lieutenant General Masao Baba, tried for his involvement in the horrific Sandakan death march, surrendered, capturing key moments on camera.

While he is candid about the reality of war and his experience in it, he is far from bitter.

He is warm and generous with his time, offering a “Murray River” salted caramel Tim Tam with coffee because “they’re the best” when The Advertiser visits.

He chuckles often and his stories are peppered with humorous, uncensored anecdotes about the characters he met along the way and the absurd situations he found himself in, such as being tasked with burning millions of dollars of money seized from the enemy.

“Strangely enough, I was given all the ‘evasion money’ to burn … it might have been that I had an honest face,” he laughs.

“I was under instruction to burn it all and it took quite a long time to do – all day and night as well as a bit of the next day to do it.

“There were half a dozen boxes stamped with Yokohama Specie Bank and packed tight with money – I was millionaire for a short time.”

The budding photographer and filmmaker tells of trading his ration of cigarettes for “darkroom” equipment to develop his photos under the darkness of night.

He poignantly shares how he asked his family to send some dried gum leaves in the post, to burn so he could be reminded of home.

He recalls the names of officers in his unit as he points to photos, revealing little snippets, such as cheeky ribbings between soldiers – some strictly “off-the-record” – and quietly chortling at certain memories.

He reminisces about the irreverent younger officers who would borrow his gun for nightly guard duty shifts, and return it uncleaned.

“I had a beautiful little sub machine gun and I would lend it to them … the buggers would always fire it and I would be cleaning it the next day,” he says with a smile.

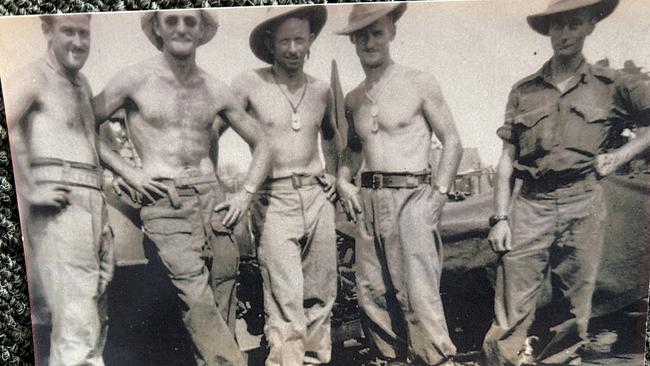

He holds up an image of himself and four drivers, taken on the eve of his unit’s planned beach landing at Borneo, shaking his head wryly as he recalls the photographer saying he’d taken it “just in case you don’t make it”.

His eyes twinkle as he remembers finally arriving back on Australian soil, months after the war had ended to be greeted by a ticker-tape parade in Brisbane.

“They loaded us into trucks and drove us down the main street … I felt little bits of paper falling on me … we were dirty, we were hungry and we were wet from a shower of rain but we didn’t care, we were going home,” he says. “It was lovely.”

He then boarded a train with his fellow South Australians, bound for his home state and arriving at 10.30am on Christmas Day in 1945.

“It was the best Christmas present I’ve ever had,” he says.

The man who has lived through both world wars and the Great Depression remains remarkably active and vibrant, in defiance of his age; he still rides his motorbike regularly and helps on the farm, attributing his sprightliness to the fact “his bones don’t match his age” – at least that is what his radiographer tells him.

“So I don’t know how old I am, I could be 90 and living under false pretences,” he laughs.

While he has rarely spoken publicly about his time at war, in a moving video message created for students of his former school – he was part of Pulteney Grammar’s Class of ‘33 – he says of his fallen comrades: “I salute them by covering my medals, because their sacrifice was greater than mine.”

He repeats these words today, uttering them with quiet sincerity and unwavering conviction:

“You cover your medal with your hand because their sacrifice is greater than yours … that is a known thing, it is set in stone.”

And South Australia salutes you – and thanks you for your service, Mr Wagener.