Chemotherapy bungle victim Andrew Knox to try stem cell treatment in bid to beat cancer

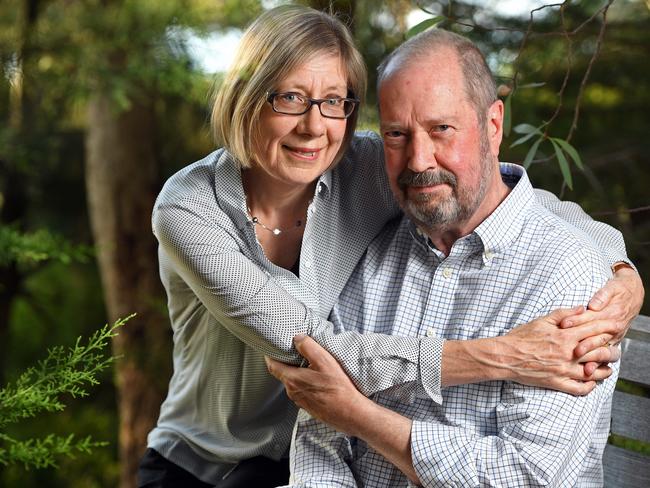

CHEMOTHERAPY underdose victim Andrew Knox will travel to Melbourne next week to begin life-or-death treatment to beat the same strain of acute myeloid leukaemia he had two years ago.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Coroner’s inquest begins as fourth victim dies

- Knox told on his birthday his cancer had returned

- Andrew Knox: This mistake may well kill me

- How a ‘typo’ denied cancer patients full treatment

- Brave chemotherapy bungle victim Bronte Higham dies

CHEMOTHERAPY underdose victim Andrew Knox will travel to Melbourne next week to begin life-or-death treatment to beat the same strain of acute myeloid leukaemia he had two years ago.

Mr Knox, who is one of seven of the ten wrongly-treated cancer patients to relapse, says the reality is he may never return home from a stem cell transplant on May 4.

Four of the relapsed patients have died and their deaths are being investigated by the South Australian coroner.

“We were all effectively programmed to relapse through ineffectual, incomplete treatment,” Mr Knox said.

“The fact that I have the same strain as before means the chemotherapy failed to do its job and now I may lose my life.”

Because the chemotherapy scandal primarily involved the Royal Adelaide Hospital, Mr Knox could not be given a transplant there even though it has the technical capability to perform them. Mr Knox said some of the RAH treating specialists would be among the group of eight whose medical conduct was referred to the disciplinary body, AHPRA, and the South Australian coroner.

“They (the RAH) agree that the transplant people involved couldn’t be seen to make objective decisions because they were involved in the underdosing and were potentially under investigation,” Mr Knox said. “That would be extraordinarily uncomfortable for all concerned.”

Mr Knox, 68, said the Austin Hospital in Heidelberg was the most skilled to deal with his particular case and he would undergo a stem cell transplant from a donor in Europe whose cells will be carried by hand to Melbourne by a medical courier.

No suitable donors could be found in Australia and Mr Knox is grateful to the unknown European, even though the treatment risks are high, initially from infections and then from rejection of the donor cells which are not a perfect match.

“To be realistic there is a significant possibility of mortality from complications but without that generosity I have no chance,” Mr Knox said. “If they didn’t find a donor, I would be gone very soon.”

He is angry that more than 18 months after the scandal came to light, and more than a year after Health Minister, Jack Snelling, referred eight people to AHPRA, no public sanctions have been incurred.

This includes staff at the RAH who caused the error and failed to alert the Flinders Medical Centre who then underdosed Mr Knox.

He will be cared for by staff at the QEH once he returns home.

“The best-case scenario for my return home is 100 days, the worst case is never,” he said. “It’s a bit of a daunting time.”