Brains trust – Our experiment in a science future

Our state’s science superheroes are forging South Australia’s bold new path to the future through cutting-edge discoveries that also promise an economic boost.

IN A STERILE laboratory in suburban Adelaide, Flinders University scientists have developed advanced DNA technology that will make criminals from all over the world nervous.

The team can now pinpoint levels of DNA so minute they believe it will help place people at the scene of crimes in a fashion never before seen.

At the same campus, a scientist has developed a dirt-cheap, non-toxic polymer that can suck mercury out of water and soil.

It is a discovery that is expected to become a game-changer in the battle against the pollutant, which can cause muscle weakness, brain damage and loss of IQ points in unborn children.

Scientists at Flinders also have had a major breakthrough in a treatment for ebola – a virus that killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa in 2014-16.

Across town, a leading scientist at the University of Adelaide has developed, in simulated wind tunnels, the world’s most aerodynamic cycling helmet.

One of his colleagues is heading up a “nation-leading trial” of a meningococcal B vaccine. Another is helping to predict when and where earthquakes may strike.

At UniSA, a professor of neuroscience has uncovered quirks with how the brain learns languages, paving the way for best-practice retraining for people who have had a stroke or brain injury.

This is just a tiny selection of the work being undertaken in South Australia – work that can and will change the world.

In less than 10 weeks, the Holden factory in Elizabeth will close its doors, heralding the final chapter for the company that started building vehicle body shells in Adelaide in 1919.

The future prosperity for the state is very much seen in STEM industries – science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Science and Information Economy Minister Kyam Maher believes Adelaide has huge potential to grow its science research sector and turn it into commercial enterprises.

“We have natural advantages in terms of the size of our city,” he tells the Sunday Mail.

“We are small enough that when you want to try something new, you can get to decision makers pretty quickly. But we are also big enough to know that if something works in Adelaide it can scale up pretty well.

“If you look at our history in SA, we have had some phenomenal scientists that have made huge differences throughout the world.”

He refers to South Australians – nuclear physicist and humanitarian Mark Oliphant, Antarctic explorer Douglas Mawson and William Lawrence Bragg and his father William Henry Bragg, winners of the Nobel prize in physics in 1915 – as examples.

“I am constantly amazed with how universities are now partnering with industry and the phenomenal things that are going on,” Mr Maher says, citing the University of Adelaide’s Institute for Photonics and Advanced Sensing as a leader in the field.

Photonics is the physical science of producing, manipulating and sensing light.

“As an industry it is worth about $500 billion globally and is expected to grow to about $600 billion,” he says. “It is one of the huge growth areas and the institute, set up by Tanya Monro, is doing some really interesting work.

“(Global science and medical company) Trajan have set up an office inside the institute because they have been so impressed they want to see it at ground level and consider the commercial implications.”

Nanoscale (meaning working at the nanometre scale) biophotonics (the science of generating and harnessing light – photons – to image, detect and manipulate biological systems) is another area in South Australia also on the Science Minister’s radar.

“Led by Professor Mark Hutchinson at Adelaide Uni, they are doing measurements that we have never been able to measure before,” Mr Maher says. “Measuring in real time the fat content of milk as it passes through a dairy, measuring markers in meat to determine meat quality – fat and protein analysis.

“Some of the other interesting research they are doing is in pain detection. Pain is often measured subjectively by asking people, but there are ways to scientifically quantify that.

“They are using advanced sensing to look at the colour of blood as a marker for the levels of pain, which has huge implications for infants or people with dementia who can’t reliably talk to you about their pain.”

Innovation and commercialisation is seen as one of the keys to driving SA’s STEM-based economy.

In the past year, the State Government has given seeding grant funding to about 30 enterprises under the South Australian Early Commercialisation Fund to turn ideas into solid business ventures. The fund will provide eligible companies and organisations with grants of up to $500,000.

The ideas cover a raft of areas, including medicine, business, technology and computer gaming.

Beta Cell Technologies is working on a seeding device to support the process of developing an ectopic skin pancreas that has the potential to treat and cure Type 1 diabetes – a chronic lifelong disease that affects more than 142,000 Australians and 1.25 million in the US each year.

A world-first commercial system for automated analysis of asbestos air monitoring samples, being developed by First Frontier, promises greater efficiency and accuracy in testing.

Adelaide Crows footballers have been helping in trials of a unique hydration drink, by Flinders Partners, which reduced fluid loss during exercise by 35 per cent and rehydrated players in recovery nearly six times faster than leading sports drinks.

Inovor Technologies has established a small satellite manufacturing facility in Adelaide with the hopes of delivering its first spacecraft next year.

Life Whisperer Technologies is developing artificial intelligence-driven decision support for early detection of viable embryos for IVF implantation in a bid to help the estimated one in six couples in Australia who are unable to have children naturally.

The artificial intelligence can differentiate key features of embryos that a human eye cannot effectively discern and avoid invasive testing that can risk damage to the embryo.

The use of drones in everything from aerial photography to agriculture has grown significantly in recent years. But technology has been limited by the amount of time drones can stay in the air.

Praxis Aeronautics has developed drones powered by solar technology with flight duration of about six hours, compared to electric drones that fly for up to about one hour.

Developers are confident the technology can be used for mining and geospatial mapping, public safety functions (shark spotting, fire control, civil disobedience and surveillance), animal, environmental and conservation management, and medical supplies distribution to isolated or remote communities.

Each of the ventures have the possibility to create industries with not only world-changing breakthroughs but workforce pathways for South Australians.

Between the South Australian Parliament and the new Royal Adelaide Hospital, on North Tce, is the unmissable honeycomb-like facade of the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute.

SAHMRI, as it is more commonly known, is an independent health and medical research institute composed of about 600 local and overseas researchers.

The website for SAHMRI declares: “We’re fighting cancer, premature birth, infectious disease, depression, heart disease, Aboriginal health disparities, diabetes and dementia, in the hope that you or someone you know won’t have to.”

SAHMRI acting executive director Steve Nicholls told the Sunday Mail that research work in South Australia was critical.

“Our hospitals are full and we still have a lot of people that are dying prematurely,” Prof Nicholls says.

“We have health issues that expand across our community, in all socio-demographics but are particularly worst in disadvantaged regions.”

Prof Nicholls says South Australian scientists are conducting world-leading research in heart disease, cancer, diabetes and Aboriginal health.

“That research spans from early discovery at the bench to the clinical trials to show that the drugs work,” he says.

Despite the great progress in SA there are challenges, he says.

“Research is expensive and we not only need a larger slice of the government funding pie but we also need to be smart and find innovate ways to fund research,” Prof Nicholls says.

“We need to be better at philanthropy. South Australia has not been successful in being able to leverage funding from philanthropy and the corporate sector for research.

“We are a smaller population and a smaller proportion of research funding.

“We think that biomedical research presents a great opportunity not only in health care but as stimulus for the economy. We are now running multinational trials out of Adelaide.”

In the Old Stock Exchange building in Adelaide’s CBD, Royal Institution of Australia chief executive Bradley Abraham proudly discusses the effect Australia’s Science Channel is having in spreading the word about all things science.

The channel is the online presence of the institution, the national scientific not-for-profit organisation with a mission to inspire “people to connect with science in all its shapes and forms every day”.

Mr Abraham says that “STEM is pretty much the building blocks of the way we live”.

“Everything we do in our daily lives, there is a very heavy STEM capacity to it, from the medicines we take, the coffee we drink and the cars we drive,” he says.

Mr Abraham says STEM jobs are becoming increasingly appealing to young people, but many parents are still in the dark.

“The traditional view of scientists being in lab coats, working with test tubes or Petri dishes is such a narrow view of STEM it is not funny,” he says.

“There are opportunities available across a wide range of areas, including science, agriculture, technology, engineering, biodiversity, coders, app developers (and) social media experts.

“There are STEM jobs that were not available 10 years ago in (the) mainstream.

“We have not been good at selling the story of context – why STEM? Why is it important and why does it matter to kids?”

Mr Abraham says many STEM jobs are not just financially rewarding.

“Young people respond to being able to contribute rather than just earning a wage,” he says.

“STEM careers can be very well-paid careers ... but at the same time you can do something that is very meaningful with value.

“Young people want to be able to contribute to fix the world’s problems. “The majority of STEM practitioners, while they make good money, are doing things that are evolving society.”

Mr Maher says future job opportunities for South Australians lie in the STEM sector.

“It is exceptionally important that we continue the momentum that we have,” he says. “We have for half a century in Adelaide been a city that has relied on traditional manufacturing.

“There is a change that is under way that needs to keep going.

“Over the next couple of generations we will see almost $100 million of naval defence projects in Adelaide.

“Science engineering technology will be needed to solve some of the challenges of building some of the most complex machines on earth.

“But some of the spin-offs that come out of that area will also be huge. Silicon Valley was founded in the early days of naval defence projects.”

Silicon Valley is the nickname for the southern portion of the San Francisco Bay Area that now is home to many of the world’s largest hi-tech corporations. It has been estimated Silicon Valley accounts for one-third of all of the venture capital investment in the US, helping it to become a leading hub and start-up ecosystem for hi-tech innovation and scientific development.

It is not the only region of the US Mr Maher discusses when talking about Adelaide’s future. He compares Adelaide to Austin, Texas, and Boulder, Colorado – two US cities that he says have an advantage of “the sweet spot in terms of size for innovation”.

He says SA’s capital has increased its vibrancy with the rejuvenation of laneways and the success of Adelaide Oval, to rival cities like Austin.

“Creative people want to be in a place that is vibrant. That feeds the technological diversity and vibrancy that then feeds into the social and cultural vibrancy,” he says.

HELEN MARSHALL

Robinson Research Institute, University of Adelaide

Professor Helen Marshall’s research program is focused on urgent priorities in infectious disease prevention and includes clinical trials in investigational vaccines, infectious and social epidemiology and public health.

She is leading a world-first study looking into the impact and herd immunity effect of immunising against meningococcal B.

About 60,000 South Australian students, all children in Years 10, 11 and 12, have been offered the meningococcal B vaccine for free as part of a state-led study.

Her main interests include meningococcal, human papillomavirus and pertussis infections and their prevention by immunisation.

She has been an investigator on more than 50 paediatric, adolescent and adult clinical trials.

Prof Marshall’s research group VIRTU is the only centre in Australia assessing community attitudes to introduction of new vaccines.

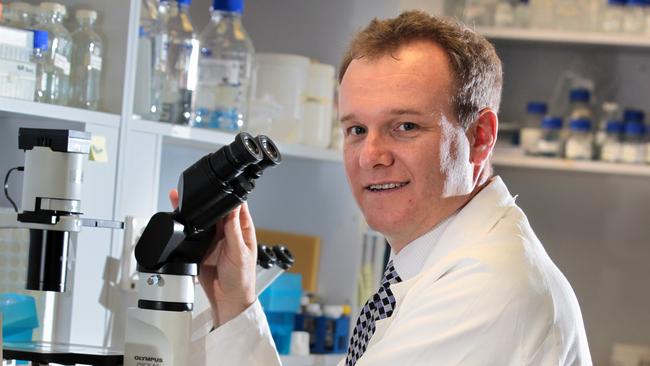

RICHARD KELSO

School of Mechanical Engineering, University of Adelaide

The world’s most aerodynamic road cycling helmets have been developed by Associate Professor Richard Kelso in Adelaide, giving an edge to 2016 Tour de France and Olympics participants with the need for speed.

It is estimated the helmets could provide an advantage of anywhere from 0.2m to 2m over competitors in a bunch sprint. In professional cycling terms, that could make the difference between wearing the winning jersey or not.

Since its release, the helmet has been worn to victory in an estimated 12 stages of European grand tours and spring classics, as well as 26 stage wins in other professional races. Overall, there have been an estimated 43 significant successes, including top-three placings in grand tours and young-rider jersey victories by riders.

ANDRE LUITEN

Chair of Experimental Physics, Institute for Photonics and Advanced Sensing, University of Adelaide

Prof Luiten and his team are developing the world’s most precise clock to boost a defence asset that safeguards Australia. The Sapphire Clock loses or gains only one second every 40 million years.

He and his team have also produced the world’s most sensitive thermometer – able to measure temperature with a precision of 30 billionths of a degree.

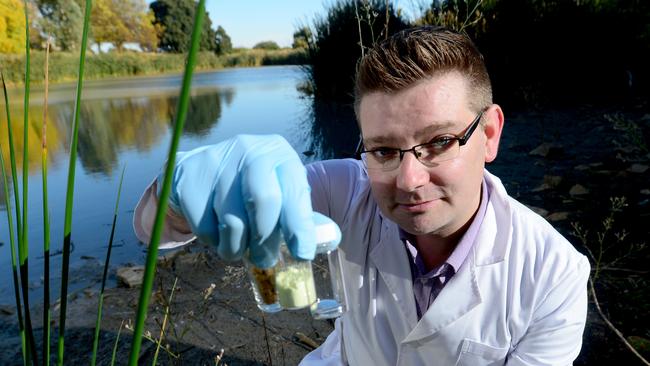

PAUL KIRKBRIDE

Professor of Forensic Science Chemical and Physical Sciences Flinders University

Professor Kirkbride is leading DNA ammunition research that should have criminals all around the world nervous.

He and his team were the first scientists in the world to match gunshot residue with specific brands of ammunition.

The research detects gunshot residue and then matches glass fragment trace elements and isotopes present with those in bullet cartridges, providing a previously unachievable level of detail about gun crimes.

Prof Kirkbride’s work assesses tiny pieces of glass that have nodules of lead and/or barium attached to them. The team has focused its attention on .22 ammunition, the most commonly used ammunition in gun crimes in Australia.

The science will be a game changer for law enforcement agencies, which have previously been unable to link some suspects with crime scenes.

STEVEN WIEDERMAN

Senior Lecturer, Adelaide Medical School, University of Adelaide

Dr Wiederman probes how brains, large and small, developed the ability to predictively focus attention on a moving target while ignoring distractions.

His team uses electrophysiological techniques (the electrical properties of biological cells and tissues) to investigate how flying insects see the world and to build robots that emulate these principles.

He has discovered a complex visual circuit in a dragonfly’s brain that could help to improve vision systems for robots.

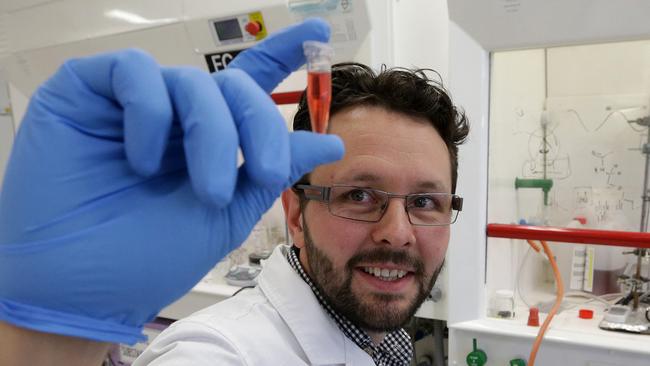

JUSTIN CHALKER

Senior lecturer, Synthetic Chemistry, Flinders University

Dr Chalker leads a team of scientists who have discovered a dirt-cheap, non-toxic polymer that can suck mercury out of water and soil.

The discovery is expected to be a game-changer in the battle against the pollutant, which can cause muscle weakness, brain damage and loss of IQ points in unborn children.

He is working on creating a plant held in a shipping container, so the polymer could be made on site in remote regions.

INA BORNKESSEL-SCHLESEWSKY

Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, UniSA

Professor Bornkessel-Schlesewsky’s research focuses on the complex interactions that happen in the brain as we learn and understand languages.

The research, into how we learn different languages, has discovered the brain learns languages as seemingly disparate as Chinese, Turkish and German in ways that are similar for the brain. Languages we would expect to have commonalities, such as German and Dutch, are processed quite differently to each other.

The research is expected to guide language retraining for people who have had a stroke or brain injury.

It may also inform aspects of artificial intelligence communications development, support innovations in the way we teach languages and also help to strengthen cognitive health into old age.

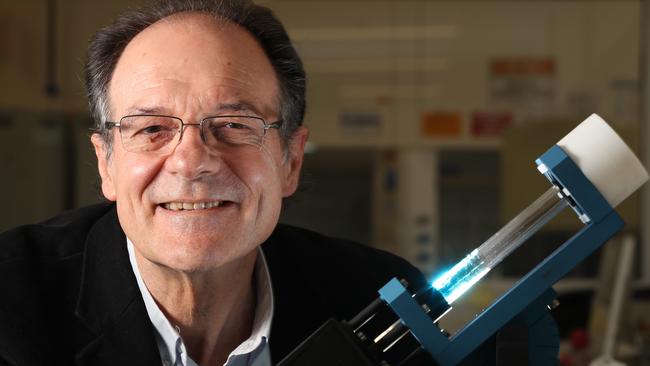

COLIN RASTON

Professor of Clean Technology Chemical and Physical Sciences Flinders University

Professor Raston was in 2015 awarded the most notorious international prize in science – the Ig Nobel Award – for finding a way to unboil an egg.

The Igs are intended to reward scientific advances that make people laugh – and think. Each year they track down the most unusual and imaginative research.

But Prof Raston’s machine, which can unravel proteins, has proved to be far more than just a gimmick.

To demonstrate the machine’s potential, they fed it a boiled egg and got an “uncooked” one back.

It was actually a serious demonstration of a groundbreaking new technology with implications for cancer treatments, pharmaceutical manufacturing and the processing of biofuels and foods.

Prof Raston has since developed a seek-and-destroy smart bomb – radiation treatment – to blast cancer tumours without harming healthy tissue.

He has now turned his attention to producing high-quality graphene, which is 200 times stronger than steel, for industrial use.

JUSTINE SMITH

Ophthalmologist, Flinders University

Professor Smith is one of Australia’s first “Superstars of STEM” charged with inspiring the next generation of female scientists.

Last month it was revealed she was part of a team of scientists who believe they have found the key to containing the deadly Ebola virus that killed thousands of people in Africa, after discovering a “super cell” they say may act as a “reservoir” to keep the virus from spreading.

She is currently leading a project to save the sight of hundreds of thousands of people suffering from the inflammatory eye disease uveitis.

PETER VEITCH

Head of Department, Physics School of Physical Sciences, University of Adelaide

In 2015 Professor Peter Veitch, with scientists from 90 universities around the world, discovered what has been described as one of the most important scientific advances of our lifetime. The team detected gravitational waves emanating from a cataclysmic collision of two black holes about 1.3 billion years ago.

It was a discovery beyond what even Einstein, who first predicted the waves’ existence, would have imagined possible.

BRONWYN GILLANDERS

Professor, School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide

Professor Gillanders’ research focuses on aquatic waters (freshwater, estuarine and marine) with a strong focus on fish and cephalopods (octopus, squid and cuttlefish) and environmental issues. SA has the only known breeding aggregation of cephalopods in the world. The iconic aggregation of giant Australian cuttlefish in upper Spencer Gulf offers an ideal opportunity for Prof Gillanders’ study. Her team has recently focused on global trends in cephalopods and is studying environmental and fisheries drivers of these trends.

ALAN COOPER

Director, Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, University of Adelaide

The 2016 South Australian Scientist of the Year has played a central role in the development of the field of ancient DNA, starting with his PhD research in the United States almost 20 years ago.

Prof Cooper currently leads the Aboriginal Heritage Project in collaboration with the South Australian Museum and Aboriginal Families and Communities around Australia, which aims to create the first DNA map of Aboriginal Australia, allowing people of Aboriginal descent to trace their heritage back beyond recent records.

One of his research projects used DNA in hair samples to help show Aboriginal people have been continuously present in the same regions of Australia for up to 50,000 years.

THE EARLY HEROES OF STEM

Some of them live on in our memories – and on our currency. Others have been forgotten. Here are a few of the brains that show the early ingenuity of SA.

■ Richard Bowyer Smith — Invented the first stump-jump plough, entitled the Vixen (1876)

■ David Unaipon — Invented an improved mechanical handpiece for shearing sheep by changing the motion of the blades from circular to straight (1909)

■ Lancelot de Mole — Mechanical engineer and inventor known for the early design of the military tank (1910)

■ Edward Both — Inventor of the first portable electrocardiograph and the “visited” — a forerunner to the modern fax machine (1940)

■ Sir Howard Florey — Joint Nobel prize winner in physiology or medicine for his role in the development of penicillin (1941)

■ Lance Hill — A motor mechanic who made the first Hill’s Hoist for his wife, whose washing kept falling off the prop washing line (1945)