Big plans for Adelaide that never happened

Now that North Adelaide’s seemingly cursed Le Cornu site has finally sold, we could see an end to years of nothing. Probably not that fancy Sheraton hotel, though. That’s just one of the many grand plans for Adelaide over the decades that never happened.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The sale of the former Le Cornu site in North Adelaide could finally see some sort of construction on a site that’s been stagnant since 1989.

Maybe — there’s hardly a history of action on that huge, empty block of land in one of Adelaide’s most high-traffic streets.

Adelaide has a history of huge ideas ending up as nothing. From man-made mountains to Victoria Park grandstands, here’s a look back at some of Adelaide’s big deals that turned into nothing. No, this isn’t an exhaustive list. We don’t have that much time. Feel free to include your suggestions in the comments below.

Nuclear waste storage repository

It was the huge idea that could deliver $100 billion to the state — but ultimately a Citizens’ Jury flatly rejected a nuclear waste dump in SA.

A Royal Commission recommended building a nuclear waste storage repository to take other countries’ low and medium-level waste in May last year.

Citing potential state revenues of $5 billion per year, it found up to 5000 jobs could have been created during the peak of construction, and about 600 full-time jobs once the facility became operational.

Premier Jay Weatherill visited the world’s most advanced high-level nuclear waste disposal facility in Finland last year to examine its set-up.

A site was never considered — the Royal Commission made it clear the community needed to be on board as well.

It wasn’t.

A little over a year ago, a Citizens’ Jury — curiously the last such voter-led group thus far — released a report overwhelmingly against the dump, citing a lack of trust in the State Government’s ability to deliver on the project, after which the Liberals withdrew their support.

A week later, Mr Weatherill said he’d like to have a referendum on the issue, but it needed bipartisan support. The plan was abandoned earlier this year.

The Multi-Function Poli

It could have been so grand. I mean, a 2km-high man-made mountain to launch spaceships?

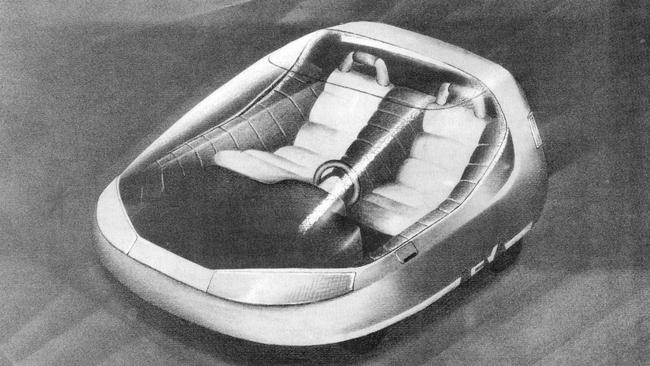

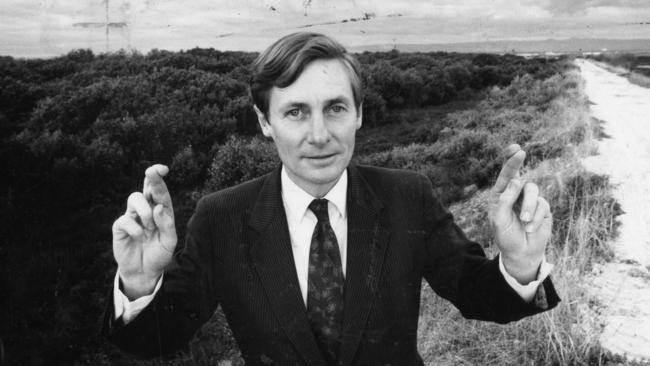

First proposed in 1987 and eventually abandoned in 1997, the Multi-Function Polis — or MFP — was supposed to be a small, super-hi-tech city built on a swamp north of Adelaide, at Gillman, led by Japanese investment.

Planned to be a utopian metropolis, with a heavy focus on integrating research, art, leisure, tourism and computers, fears of an Asian enclave ended what could have been a remarkable triumph in linking two cultures and technology. Instead, we had “two of the most expensive holes in history”

At one point it was planned that bricks for the MFP buildings would be made of reconstituted sewage, and the houses would recycle their own waste water.

By the time Gillman was chosen for the site from several across Australia, negative coverage had led to several Japanese investors pulling out.

After all, a mangrove swamp near garbage dumps was an odd choice for what was nearly a resort for rich retired Asians in Queensland.

It began to fail to attract funding, and the Federal Government pulled out in 1996.

In 1997, then-premier John Olsen announced the dream was over for SA. All that was left was two test drill holes.

But it wasn’t for nothing — the State Government built Technology Park near Mawson Lakes instead.

The ex-Le Cornu site

OK, so the jury’s still out on this one. Something could actually happen now that Adelaide City Council has bought the huge vacant lot in North Adelaide from Makris Group.

Most Adelaideans won’t hold their breath, given the very, very long history of nothing.

The first plans for the 7535 sqm site were rejected in 1991, when a retail complex — already approved — was knocked back, beginning years of argument, court challenges and appeals over building heights.

In 1997, it was going to be cinemas and a carpark. In 2005, that changed to a luxury hotel, retail shops, apartments, restaurants and a cinema when Makris Group bought it.

Two years later, the State Government took control of the site from the city council, promising to fast-track development.

The global financial crisis undid that, then a 2012 joint venture between Makris Group and billionaire property developer Lang Walker fell over in 2013.

In 2014, Makris Group revealed new plans for a $200m, eight-building shopping and apartment complex, adding a luxury Sheraton Hotel in 2015.

In July, that was gone. Fast forward to December, and we’re to have a new owner — but no actual new plan. Yet.

You can see a much more detailed timeline highlighting a litany of nothing here.

Glenelg tidal wave in the 1970s

Not everything on this list is failed plans. Sometimes, Adelaide just loses its mind.

In 1976, Melbourne housepainter and self-proclaimed clairvoyant John Nash convinced thousand of people to go to the beach and wait for a tidal wave they all knew wasn’t coming.

Nash believed he’d had a vision of Adelaide being consumed by a tidal wave and earthquake, at noon on January 9, 1976.

Bob Byrne, who writes the popular Adelaide Remember When column for The Advertiser, wrote a long piece on the day, which makes for great reading

The publicity caused a panic, with some people reportedly selling their homes, and others literally heading to the Hills and Riverland on the day, just in case.

It was said coastal properties were sold off, businesses reported a lot of sickies on the day and hotels saw a drop in occupancy.

Even the BBC sent a TV crew to Glenelg. You know, in case.

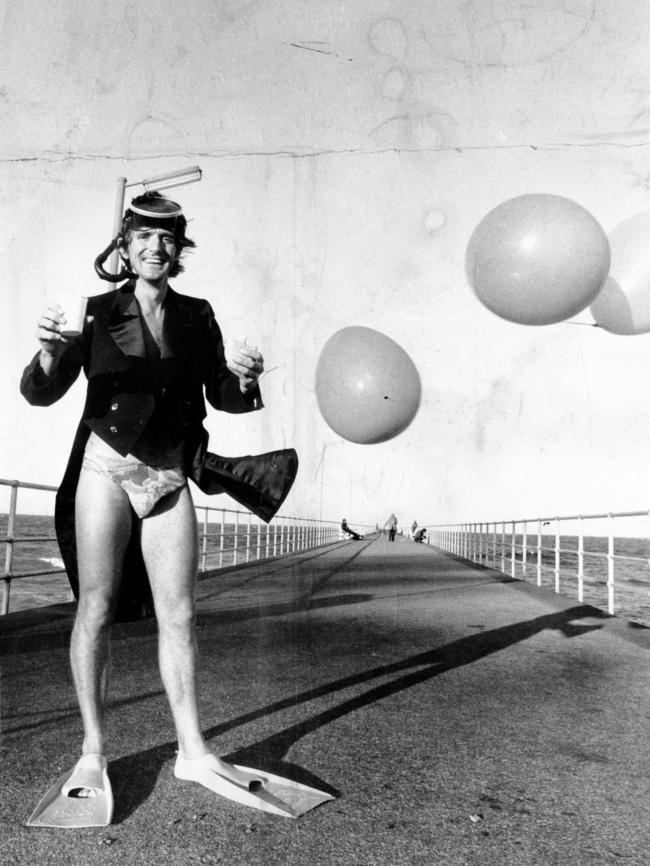

But not everyone believed it. About 2000 people headed to Glenelg, to watch the end of the state.

Advertiser columnist Rex Jory, who wrote about the event in 2006, headed down for the party, saying “the mood of the crowd was somewhere between hysteria and hilarity”.

Then-premier Don Dunstan joined in, appearing on the balcony of the Pier Hotel and told the crowd nothing would happen.

Some wore flippers and goggles, another arrived in a suit and top hat, to go out in style.

The crowd counted down to noon — and as you all know, no wave. No earthquake.

It’s said Nash moved to a small country town in NSW, which was hit by floods not long after his arrival.

If anyone can put us in contact with Mr Nash, we’d love to hear from you.

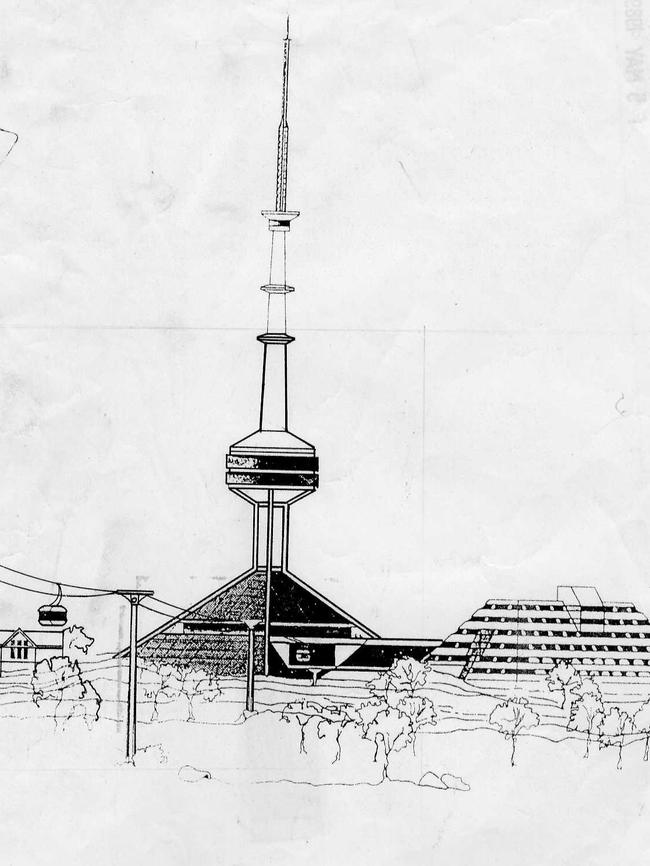

Cleland cable car — the 1986 version

A couple of weeks ago, the State Government revealed a Hong Kong entrepreneur-led plan for a cable car between Cleland National Park and Mt Lofty Botanic Garden summit, new hotel and treetop walk for the wildlife sanctuary.

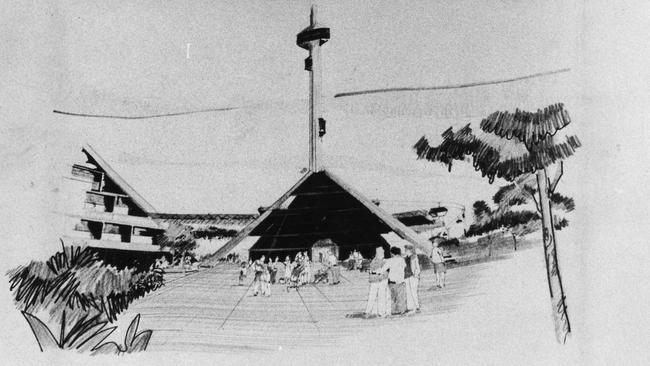

Quite a literally a groundbreaking idea, and it was also that back in 1986, when it was first suggested, along with a hotel — and then dumped three years later over fears for the environment.

The 6km cable car would have run from the eastern side of Beaumont to just below Mount Lofty Summit, stopping at Waterfall Gully and Cleland wildlife park along the way.

It would have ended at a station inside a 200m communication tower, the central feature of a tourist centre incorporating a 100-room hotel, three restaurants and a kiosk, costing about $140m in today’s money.

The plan included a revolving restaurant, a viewing platform, and restoring St Michael’s Anglican monastery, which was destroyed in the 1983 Ash Wednesday bushfires and bought by the State Government.

The Stirling Council opposed the plan, calling it “two black pyramids”.

That opposition grew, especially over potential damage to the surrounding environment and the project’s scale, and saw the plan scrapped and replaced with a $15 million bistro.

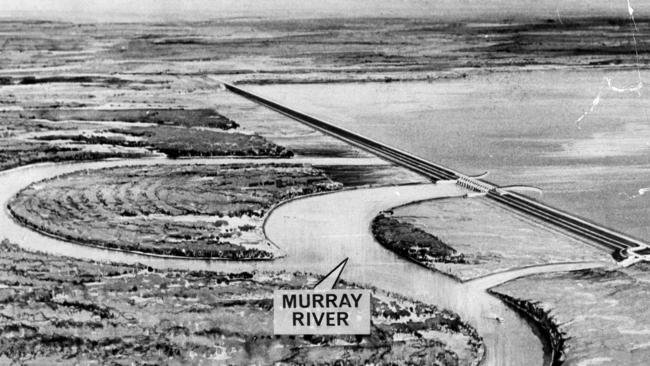

Chowilla Dam

It would have been one of the largest reservoirs in Australia in the 1960s, but the Chowilla Dam wound up nothing more than maps, paintings and a 23km railway line to nowhere — and the beginning of Don Dunstan’s reign as SA’s premier.

Proposed in 1960 by then-premier Tom Playford, the dam was to provide reliable water supplies for SA by creating a massive reservoir upstream of Renmark.

The dam wall would have been in SA, but the reservoir would have stretched into Victoria and NSW, and been about 1400 sq km.

The stats were impressive — a 1968 pamphlet from the State Government lists an earth embankment 5.5km long, with a 240m spillway. The depth was to be up to 17m, creating a relatively shallow reservoir, which produced the problem of evaporation.

The SA, NSW, and Victorian governments agreed in 1963, and a railway line to transport the rock was built. Three trains were even ordered.

The plan was to block the Murray in the Chowilla floodplain, but environmental concerns about increased downstream salinity, huge amounts of evaporation in a hot dry climate, and flooding the Chowilla wetlands led to protests.

It became political — the dam would have been in independent MP Tom Stott’s electorate, and his vote helped Playford win the 1962 election. But the Liberal leadership switched to Steele Hall, who in the late 60s decided Chowilla wasn’t a good idea and favoured water from Dartmouth Dam, in northeastern Victoria instead.

Costs to build Chowilla were spiralling — from about $256m in today’s money in 1960 to $810m in 1968, and environmental protests were growing.

When Hall dropped his support, Scott switched to Don Dunstan, who was elected in 1970.

When the Victorian Government dropped its support, Chowilla was eventually dumped.

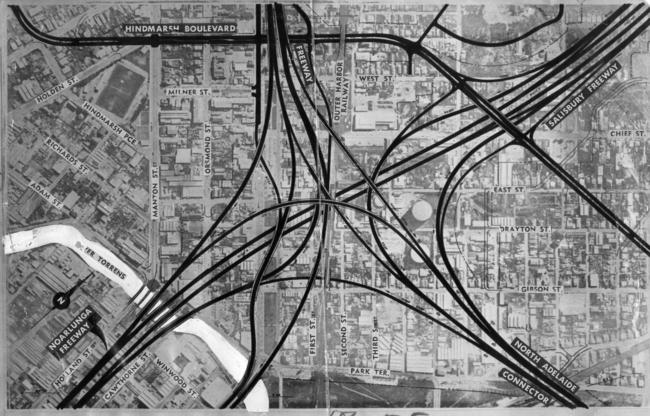

The MATS plan

Had the Metropolitan Adelaide Transport Study gone ahead, our city would have looked very different. There’d be a highway through Norwood and a subway under King William St.

Released in 1968, the plan recommended freeways, an expressway, widening existing roads, new arterial roads, a new bridge over the Port River and upgrading train lines.

The cost was staggering — $5.2 billion in today’s money.

It included a North-South freeway, referred to as the Noarlunga freeway, which was the centrepiece of the plan, a Port freeway, Hindmarsh interchange with connector to a Modbury Freeway, an eastern freeway connecting the under-construction South-Eastern Freeway to the CBD that would have gone through St Peters and Norwood, and a Foothills Freeway.

A Dry Creek Expressway was also recommended, a Glenelg Expressway (in place of the tram line) and upgrading much of Main South Rd to an expressway to Reynella.

A huge number of properties needed to be bought and demolished — 3000 for the Noarlunga freeway, including 800 homes. Hilton wouldn’t exist, and neither would Hindmarsh, possibly replaced with four levels of interchanges. Millions was spent buying homes in Hindmarsh.

The reaction was vicious. People didn’t think such a huge plan was necessary, there were fears about forced property buyouts, and many were worried about demolishing historic homes in the inner southeast.

As well, there were fears of the impact of freeways on Adelaide’s landscape — dividing neighbourhoods and creating “ghettos”, as had happened in America.

The government was going ahead, albeit with some changes, and vast tracts of land were bought in preparation.

Then in 1970, Don Dunstan came into power and MATS was shelved — sort of.

He didn’t immediately sell off all the land bought for MATS — the Festival Centre was eventually built on the space set aside for the subway.

An O-Bahn was built instead of the Modbury freeway. The Southern Expressway partly follows the original plan for the Noarlunga freeway.

You can read more detail on the planned freeways here.

Rex Jory wrote a piece about the MATS plan here.

Monarto satellite city

The town best known for lions was almost Adelaide’s second city.

In the 1970s, worried about population growth, premier Don Dunstan proposed a satellite city at Monarto, planned for about 200,000 by the end of the century.

To have its own identity, Monarto was to be the ideal city — to start as a small town, and end up a “new vision of Australian city” — townhouses, inner-city bicycles lanes, parks. A small city, with established light industries, it was to be part of Dunstan’s plan to spread South Australia’s industries across the state.

Farmland was compulsorily acquired for the city, with farmers selling their livestock and leaving their properties. Tens of thousands of trees were planted to beautify the area.

But the city never went ahead. Population growth wasn’t as much as expected, and the federal government withdrew its funding. Private enterprise never got behind the project.

The project was abandoned, and instead, Monarto Zoo was built on land already bought.

The Clipsal grandstand

File this one under “never mess with the parklands”.

In 2001, a 2500-seat grandstand in Victoria Park — as well as permanent car racing facilities — was proposed

The facility would have been built south of the grandstand, incorporating a ground-level area to be used as 52 pit garages for car racing and as a betting area for horse races.

Upstairs would have been catering facilities, a dining area, lounges, viewing terraces and a viewing concourse.

This new building would have had 2500 grandstand seats, a media centre, corporate suites and a control tower.

Essentially, then-premier John Olsen was proposing turning the racecourse into a precinct for racing both horses and cars.

Originally to cost about $24 million, by 2004 the plans began to include facilities for sports including cricket, soccer and even in-line skating, rebuilding the horse track and a double-sided grandstand — to cost about $34 million.

In 2006, then-Treasurer Kevin Foley revealed a “sleek new grandstand” with a $55 million upgrade of Victoria Park.

Opposition was fierce because of the impact on Adelaide’s parklands. The Adelaide City Council was largely opposed, and the Adelaide Parklands Authority rejected it in 2007.

Later that year, the State Government gave up on the project and decided to use a temporary grandstand for the Clipsal.

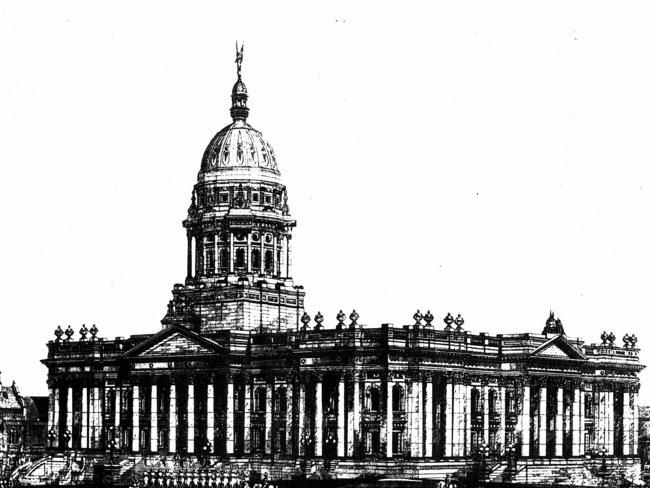

Dome on top of Parliament House

South Australia’s Parliament House is technically unfinished. The original plan included not only a dome, but towers.

The chosen design was Greek Revival, with ornate columns and a dome atop a tower.

Construction on Parliament House’s West Wing began in 1874, and was finished in 1889, but the three towers and dome were removed because of a lack of funds.

The lower house had a new home, but the legislative committee met in old parliament house for several decades, because economic depression hit in the 1890s.

Designs for the East Wing were finished in 1913, but World War One delayed construction again — it didn’t begin until the 1930s, thanks to a gift of money from Sir John Bonython

The money was used to create jobs during the Great Depression, and the East Wing was finished in 1939 — without tower or dome.

Port Road canal

Ever wondered why there’s a huge strip of land running down the middle of Port Rd?

You can thank Colonel Light — his original Adelaide town plan was for a canal right down the middle of Port Rd, running from the Torrens River to Port Adelaide, as well as a railway line.

Called the Grand Junction Canal, the idea was to easily ferry goods from ships docked at the Port to the CBD.

Colonel Light didn’t get along with Governor Hindmarsh, who wanted South Australia’s capital built at Port Adelaide.

But Light won, and the port became a port. Meanwhile, goods, produce, livestock and people were coming to South Australia, and Colonel Light planned for a man-made canal that could float what Adelaide needed straight to it.

It was never built because of the massive investment required at the time.

The South Australian Register in 1851 reported on a private exhibition of drawings showing the proposed canal and railway, noting “the cost, we suspect, will not be trifling”.