AFL nude photo scandal prompts ‘deepfake’ fears: What are deepfakes and how to protect yourself?

Senior AFL figures say AI technology or image doctoring could be behind a massive nude photo leak – but what are deepfakes, and how dangerous are they?

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Senior AFL figures say a number of photos leaked in what has been dubbed a “major privacy breach” are likely not legitimate, prompting questions over whether “deep fake” technology or image doctoring could have been involved in their creation.

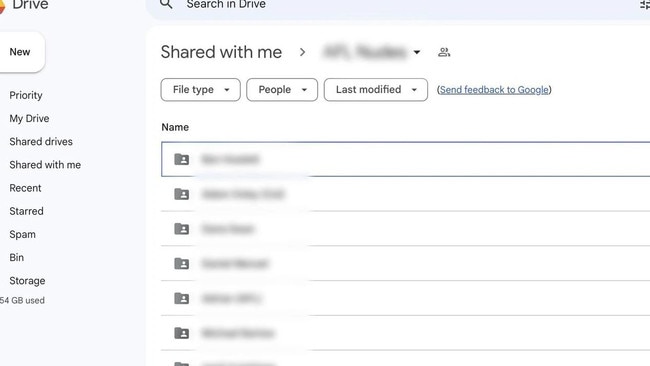

The AFL has launched an investigation into the shocking Google Drive collection of images, first revealed by the Herald Sun on Wednesday.

Each player’s name is accompanied by a folder of explicit, graphic photos and images purportedly of them. Of the 45 names, a dozen either play for the Crows or Port Adelaide or are originally from SA.

While video, images and screenshots of private messages are clearly identifiable, showing the face, or tattoos, of players, The Advertiser has chosen not to name any players. Some of the graphic images are completely unidentifiable.

A number of the pictures appear to have been sent via social media platforms Snapchat or Instagram, with features of both platforms seen on the images and what appear to be players’ profile pictures attached.

While The Advertiser has not yet verified the authenticity of any images, senior figures in the AFL – including the Players’ Association and Brownlow Medallist Jimmy Bartel – have suggested a majority of the images may not be real, potentially involving artificial intelligence “deep fakes” or image doctoring.

With platforms such as Photoshop, doctoring an image to appear as though it had been sent from a particular social media account by adding features of that account or a profile image is possible using simple photo editing technology.

Photo editing programs can also be used to edit tattoos or superimpose a different face on an image

While AI deepfake technology is more challenging to access – it requires a powerful computer, access to online tools, hours of effort and expertise – it can be used to create realistic photos and videos using a person’s likeness.

In April this year, a former counter-terrorism expert suggested that deepfake pornography posed a real threat to Australia’s athletes, warning that sporting agencies and government bodies had moved too slowly to act against emerging technology.

What are deepfakes?

The release of the images has raised questions around the rise of deepfake technology – the use of artificial intelligence software to create a hyper-realistic photo, video or audio depiction of a real person. The videos are almost impossible to identify as fakes with the naked eye.

The technology rose to prominence in 2017, when a Reddit user posed doctored pornography clips of celebrities’ faces superimposed onto porn performers.

This year, AI generated deepfakes have emerged of former Sunrise host David ‘Kochie’ Koch and former US president Donald Trump, while popular female online gaming streamers were targeted by deepfake pornography of themselves.

Australia’s eSafety Commissioner raised concerns over the rise of deepfakes, saying the technology – which is often used to create pornographic material involving the likeness of real people – poses an “unacceptably high” risk to individuals.

Last year the eSafety Commissioner handled 4169 reports of image-based abuse, a 55 per cent increase from year prior, with about 1 per cent of those relating to digitally-altered images.

A 2019 study by Sensity AI, a company tracking deepfake videos, found that 96 per cent of those created were pornographic.

The technology has also been weaponised to create false news or hoaxes, as a tool for identity theft, for sexual exploitation, intimidation and harassment.

Acting eSafety Commissioner Toby Dagg said while there were currently very few complaints regarding deepfakes, the explosion of generative AI had made the technology more publicly accessible.

“Given fact that there are models now that have been jailbroken or are circulating without any central control over them, we expect the prevalence of deep fakes to increase,” Mr Dagg said.

“There aren’t any safety standards that can be applied to the use of those models. We want to ensure that companies are being very careful about the decisions they make to open source technology like this … (and are) putting guardrails around these incredibly powerful, novel, revolutionary technologies.”

How to spot a deepfake or doctored image

While it can be difficult, the eSafety Commissioner says there are ways to identify fake photos and videos.

Often, deepfakes will have blurring, cropping or pixelation around the mouth, eyes and neck of the person as well as skin inconsistency or discolouration.

Other signs include inconsistency in the video, such as glitches or sections of lower quality, changes in lighting, badly-synched sound or irregular blinking or movement.

“One of the telltales often is if an image contains background details, sometimes that background detail won‘t make sense. Text in the background won’t be legible, sensible human text – it will be the AI model’s attempt at mimicking text,” Mr Dagg said.

“Sometimes, depending on the sophistication of the model, you can see some strange defamations around things like fingers or ears or earrings that give away a synthetic image.”

How can you protect yourself against doctored images or deepfakes?

The eSafety Commissioner says prevention of deepfakes is currently incredibly difficult – all it takes to create an image is access to enough “training material”, such as photos or videos, to feed to the AI.

While Australia currently has no specific laws around the misuse of deepfake technology, image-based abuse is covered as a civil offence by the federal Online Safety Act – which can impose fines for perpetrators who share explicit images or video without consent.

“People should be aware of the options that are available to them. Once they become aware of this kind of material circulating, they can report to esafety.gov.au and we can take action to remove the material,” Mr Dagg said.

“We're able to do that rapidly and, in 90 per cent of cases, succeed just on a request. But if we also identify a perpetrator, then we can consider remedial action against that person, requiring them to do things like delete all material in their possession.”

In South Australia, the filming and distribution of explicit images or “revenge porn” is covered under the Summary Offences Act. Deepfakes are not specifically covered under the Act.

The distribution of invasive images can result in two years’ imprisonment or fines up to $10,000, but the breadth of the law has not yet been tested in SA for deepfake pornography.