One drug. Four mums. Four dead children and the devastating ripple effect

After headlines, funerals and coronial inquests fade, the devastated loved ones of those claimed by MDMA overdoses at music festivals are left trying to make sense of their loss. Four mothers bound by grief share their stories ahead of another long, hot summer of music festivals.

The Ripple Effect

Don't miss out on the headlines from The Ripple Effect. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Ripple Effect is a confronting, challenging, raw and emotional special multimedia series looking at how illicit drugs are devastating Australian families. Four courageous mothers, all bound by the grief of losing a child to an overdose, share their personal stories.

Jennie Ross-King is grappling with the beast that is grief.

It’s been more than 10 months since she buried her only daughter, 19-year-old Alexandra, but grief cruelly tricks and teases her with games of hope on some days, then threatens to drown her with cruel reality on others.

“You convince yourself they are coming home,” Ms Ross-King tells The Ripple Effect.

“It is all very surreal still. I can’t explain it but I still don’t believe that it has happened.

“So many people say it gets better with time but it gets worse, it gets harder to wake up and convince yourself that it didn’t happen and harder to trick yourself that they are just away or they are going to come home soon.

“As time passes, you realise they are not coming home.”

Losing a parent is like losing the past but, when you lose a child, you lose the future.

The old adage hits Jennie with stark reality.

“I don’t have a future,” she says. “I don’t have any more children, I’m not going to have grandchildren. Mine and Alex’s family tree stops here.”

THAT DAY

It was on a hot and humid day on January 12 this year when Alex arrived at the FOMO music festival in Parramatta. She had already taken three-quarters of a MDMA tablet on the party bus she and her friends travelled on from their Central Coast home.

When she arrived she called her mum and reassured her she was safe.

“I love you,” Alex said on the phone to her mother.

“I love you too,” Jennie replied.

They were the last words mother and daughter said to each other.

Alex took two more pills before going into the festival to avoid being caught.

As the mercury climbed to 35 degrees, Alex began to overheat.

Jennie was sweating as she planted a tree in her backyard in Lisarow, just north of Gosford and about an hour’s drive from Parramatta. Jennie felt the tug of maternal concern and grabbed her phone to send another reminder to Alex to drink plenty of water.

The message remained unopened because at that moment Alex was in crisis in the medical tent. Her body temperature was over 40 degrees.

“She was grinding her jaw, a sign of MDMA intoxication, she became agitated and a doctor with NSW Health got Alex to hospital as quickly as they could,” Jennie says.

From the hospital, Alex’s friend called Jennie. He was frantic. “I was calming him down but I was still oblivious to how serious the situation was,” Jennie adds.

She and her partner Andrew got into their car and started driving toward Westmead Hospital.

“We were less than five minutes in and (the friend) called again,” Jennie says.

“I said I need to speak to a doctor, put a doctor on. Then the doctor came on asked me to pull over: ‘It was important I was safe’. I got a bit frustrated, I said: ‘Tell me now’ and he said he wouldn’t until I pulled over.

“When I did, he told me Alex had gone into cardiac arrest, it made no sense, I don’t know what was said after that.”

In the emergency department of Westmead Hospital later that evening, Jennie sat by her only child as doctors removed the automated chest compression machine that was mechanically pumping the 19-year-old’s heart.

There was nothing more they could do for her.

Jennie learnt quickly what MDMA had done to her beautiful daughter’s healthy body.

“The doctor came in and she was visibly upset, she said they had tried to put her on a heart lung machine but they weren’t able to put in a line as a result of the overheating of her body,” Jennie continues.

“They said there was nothing more they could do and asked me if I wanted to be with her.

“I sat with Alex for some time as they stopped the manual resuscitation and she fell asleep.

“That is what she looked like, she was asleep.

“I spent some time with her, I don’t remember how much time and that was that.”

HELPLESSNESS

Alexandra Ross-King’s funeral will forever stay in Father Rod Bower’s mind. The Anglican priest has conducted hundreds of funerals over a 30-year career but none like this one.

“This is one that has a particular effect on me as a priest,” he tells The Ripple Effect.

“It is the helplessness. As a pastor, you want to bring some comfort to each family but the grief is so intense and uncontainable, you become overwhelmed by it.

“The normal professional protections you have in such situations just don’t work. As a priest when you are working with people experiencing deep emotions, you seek to be deeply present, you also need to remain somewhat separated from that in order to function, otherwise you can’t stand at the altar in fits of tears like everyone else because you have a job to do.

“But in a situation where the grief is just so intense, it is impossible not to experience that in your own being.”

Tears welling and his voice faltering, Fr Bowers adds: “I can feel the emotion as I do now.

“As I stood beside Alex’s coffin, I was overwhelmed with the intense tragedy of the situation.

“Someone so full of life and joy and a deep desire to engage in life and living and for that life to be taken away in such tragic circumstances is just so, so sad.

“I can still feel it when I talk to you, I can feel the pain of the family. I can’t begin to imagine what it must be like for Alex’s family.”

‘I’M SORRY’

Craig Watkins is also deeply affected by Alex’s death. He is the paramedic who was called to take Alex to hospital in her critical state.

“You can ask any paramedic and they will tell you one of the hardest parts of our job is dealing with loss of life, particular young lives who are taken away prematurely,” Mr Watkins, a 19-year veteran, tells The Ripple Effect.

“I have worked at countless music festivals and concerts where I have seen and felt first-hand the devastating effects one decision can have.

“Obviously the death of a young person is tragic to all those that knew and loved them. However, the impact is felt far greater than that. I wish people could see and understand the enormous effort that goes in to trying to resuscitate a young life.

“I have been there, too many times. It’s crazy, it’s horrible, and it is absolutely devastating.”

Mr Watkins and his partner that day remain haunted by the outcome.

“I have witnessed first-hand the damage these incidents have on paramedics,” he says.

“I have cried with my colleagues and shared their heartache. I’ve seen them struggle and ask the questions: “What else could I have done? Could I have done more to save them?”

For Alex he had one simple message.

“I don’t know you and you don’t know me but I want you to know that I tried my best and I’m sorry.”

UNYIELDING GRIEF

Jennie admits all her days now start the same way.

“I still wake up every morning and remind myself what happened,” she says.

“The emptiness, the numbness, the sorrow and the weight is just so heavy.

“It doesn’t go away, it just doesn’t disappear and it is a ripple effect.

“I do a lot of my grieving, and it may be unhealthy, I do a lot of it privately because I don’t want my family to worry about it, so I spend time by myself and try to get it all out before Andrew gets home or mum is coming over and I just, I don’t want them to go: ‘She is getting worse’ — I don’t want them to worry about me.”

Jennie worries about Alex’s friends as well, who are also hurting.

Mackenzie, who asked to withhold his surname, was Alex’s high school sweetheart from age 16. He was with Alex the day she died and is heartbroken.

“It has been a hard time, but I do know something has to change so this doesn’t happen to another young person, and their family,” he says.

He wrote a letter to the girl he always loved the day after she died.

“Al, my friend, my best friend, my lover and my hater! You, gorgeous, made my world go round and not having you by my side for the rest of my life will be the hardest thing I will ever have to do. The small time I got to spend with you, I will never forget and this small amount of time we were together will be the one of the biggest highlights of my life. The impacts you made on me, both good and bad, I will cherish forever. You always, always told me, to stop being who other people want you to be and start being who you want to be. ‘Don’t want to do things for me or anyone else, want to do things for yourself’. I always kinda struggled to do that, so now if I can promise you one thing, it’s that I’m going to do exactly that. I’ll try my hardest to keep making you proud and even on my worst of days I know you’ll be guiding me in the right direction. Al, I love and miss you more than life itself. I hope you’re having the time of your life up there! I’ll see you soon enough I’m sure of it!!”

Jennie is protective of Alex’s friends and fears for their vulnerability.

She admits they are “not doing too well”.

A BURDEN SHARED

Julie Tam feels for Jennie.

The pair met at the NSW coronial inquest into their children’s deaths. Julie had three kids, her youngest, Joshua died two weeks before Alex, in similar circumstances but, in the scheme of counting blessings in bleak times, Julie has two grandchildren she is thankful for.

“That is something that resonates with me with Jen,” Julia says.

“Here we are counting our blessings, it is so hard but when you remember all six parents are feeling the same but we go forward our different ways and Jen will never get that experience.

“In that way it is a blessing for us and an additional difficulty for her, that’s what happens when you lose your children, you lose their future and you lose your future and their siblings future moments.”

Julie and John Tam had a perfect life. They were high school sweethearts who fell for each other at 16 and had been together for four decades.

They were blessed with three beautiful children, one grandchild and another on the way and they had yet to even lose a parent.

Life was very good.

When Julie kissed her 22-year-old son Josh goodbye last December knowing he was heading off on a road trip to the Lost Paradise music festival on the NSW Central Coast, the Brisbane mum worried about the long trip.

“Drive safe to the festival, it’s going to be a long drive,” she told him.

He flashed his heartbreaker smile. “You know mum, boys and long drives,” he teased.

Julie had almost graduated from the fearful lie-awake-at-night routine of parents with teens and the necessary process of cutting the apron strings.

“He was 22, so I thought, by the time they are 22 they almost home and hosed, so the biggest threat for boys at that age is driving. So that was my final parting warning because I thought that is all I had to be worried about,” Julie recalls.

A KNOCK ON THE DOOR

Just after 11pm on December 29, she was roused by a phone call. It was the police.

The family were holidaying in Coolum on the Sunshine Coast and the officer was knocking on the door of home in Ashgrove.

“I’d just gone off to sleep,” she says.

“It was a police officer who was outside our unit in Brisbane. I honestly thought she was going to say he’s hurt himself or he’s been arrested doing something silly.

“I said: ‘Is it Josh?’ I expected her to say something kinder than” ‘I’m sorry but your son has passed away’.

“You don’t go back from those words and our world changed, completely, irrevocably …”

(Julie whispers this as if to soften the devastating words).

“I felt him in the room with me at that point,” she continues. “I said out aloud: ‘I forgive you Josh’. I felt him physically carrying me because he would have felt sorry and he would have thought: ‘Mum will crash and burn’.”

Josh had taken a “crystal-like rock” of MDMA but what Julie now knows is that the purity of the cheap drug is more concentrated on the market at present, more potent than what it would have been on Josh’s earlier experimental ecstasy outings.

Josh had also been separated from his friends.

“The drugs now are so incredibly strong and Josh had what he thought was an appropriate dosage, although there is no appropriate dosage, none of us want them to do it, he took what he thought was harmless but in hindsight was probably four times as strong as he thought,” she adds.

“So that in itself was one part of the dominoes to be down there in 30-40 degree temperatures and we now know MDMA increased the body temperature and turns off the regulator, so you don’t even know you are overheating and organs start to fail because they can’t cope.

“These are the things young people don’t realise.”

ON THE FRONTLINE

An overworked GP by the name of Dr Krishna Sura had tried to save Julie Tam’s youngest child in the Lost Paradise medical tent when his body temperature was a perilous 43.4C.

“It doesn’t matter how good a doctor you are, there was nothing that could have been done, he was too far gone, sometimes they are just too far gone,” the 36-year-old Maroubra doctor tells The Ripple Effect.

Amid the chaotic backdrop of 12,000 revellers, with not enough IV fluids “zero sharps containers, no sinks to wash hands in, no gloves, barely any set-up” and dozens of passed-out kids, the images of Josh have stayed with Dr Sura.

“I spent five minutes with him and we could see the gravity of the situation and we were not equipped to deal with it, and regardless, he belonged in a hospital ASAP,” Dr Sura says, adding he saw many other young people come close to the same fate.

“I have the image of him combating us trying to get lines in, in my head, but we are doctors and this is what we are taught to deal with but it doesn’t make it easier. It’s horrible, it is horrible and you wouldn’t wish it on anyone.

“They are very close to death, so close to death.”

Julie and John flew down to Newcastle on New Year’s Day. A social worker organised for them to see their son.

“In many ways, until you see them you don’t really truly believe it but it was a horrible moment,” Julie says.

“Because it was as hot as it was, he didn’t look himself. That was very difficult, we could see it was him but the effects that the heat and the toxins have on the body is not something you can ever prepare for.”

AMAZING COMPASSION

In her stairwell today, Julie has assembled the “Shrine of Josh” to erase those haunting images. Photos of a little boy with the cheeky smile, a footy player, a handsome teen with perfect teeth and caramel skin, compliments of his dad’s Papua New Guinean heritage.

“I can’t walk down the stairs without kissing him,” Julie adds.

And it was this Josh that Julie wanted Dr Sura to know after he gave his frank testimony at the inquest. And it was an act of kindness Dr Sura will remember for a lifetime.

“She pulled me aside at the inquest and she showed me photos of what he looked like when he was well, she said: ‘I don’t want you to have the last image of him when you saw him last’ and it was very kind of her, she is amazing and compassionate,” Dr Sura says.

Since Josh died, Julie and John have paused at 7.52pm every Saturday, the time Josh was pronounced dead.

“It was very difficult but for John and I, it helped and we did it every Saturday up until about three weeks ago when Emily (Josh’s big sister) said she can’t do that anymore,” Julie says.

This “mamma bear” — as she calls herself — worries for everyone else.

“We are very different at grief but John is as shattered as a dad would be, he was his son and he thought he would have him forever, he idolised the ground he walked on and he adored him,” she says.

“I worry about all of us because we are all just so broken, it’s the best word to describe it, we are literally broken and trying to piece ourselves back together knowing there is always going to be a part missing.”

ENDLESS RIPPLES

The ripple washes across all aspects of Julie’s life. After 22 years as an office manager at an engineering firm, she has just resigned.

“I’ve worked full time all my life with three kids and your whole world is paying mortgages and school fees and I’d cut back to three days a week but I just felt I needed to stop,” she says. “I just had to stop and sit at ground zero and find out how to rebuild, I was pushing through and not doing so well pushing through.

“You come to realise nothing matters, money doesn’t matter, it’s just not a factor, yes we have to pay bills but when you go to work and feel the stresses of silly work things.

“I also have grief fog, or grief brain, you just go over something over and over again and you can’t concentrate and simple things seem incredibly hard.”

And Julie has found grief is not just emotional and psychological but also physical.

“You feel like you are dying,” she says.

“Some days you feel like the knife is in your heart and physically being turned but other days it is the dull ache in the background. I understand now when people say you can die from a broken heart, you absolutely could.”

Jennie is also battling the physical effects of grief, which she too finds exhausting.

“Other than having no energy and finding it difficult to do anything. What does it matter if I get up at 8am or 10am? I don’t have any sense of taste since (and) my friend who lost her daughter to suicide three years ago, she had the same thing,” Jennie says.

To be close to her daughter, Jennie goes to Alex’s room, left as it was, and talks to her.

“I talk to her, talk to her a lot,” she says.

“I close my eyes, I do in her room, I still clean in there and open her shutters up and fix up her bed and tidy stuff and we talk, sometimes I get cross with her. If someone said to me if you knew what was going to happen and given a choice to have another child that this won’t happen to, I wouldn’t change it, despite the pain, I wouldn’t change her for anyone and I’m grateful for the 19 years I had.”

To feel close to Josh, Julie sits in his car, which she now drives with personalised number plates with his beloved Warriors footy team. And she has taken to cuddling a blue teddy bear she found in a newsagent.

“When he was born he was given a blue bear from his uncle and Joshie flogged it to pieces as he was into wrestling,” Julie adds.

“We were out shopping one day a few weeks after we lost him, we were in a newsagent and they have children’s gifts and I picked up this blue bear and I just started to cry and I was rocking like you do a baby. I put it down and walked away and then I went back and picked it up and thought I need to buy this bear.

“Because you miss the physical touch of them and that allowed me something to hold, it was something I could hold that resonated with him.”

GRIEF PLAYS CRUEL TRICKS

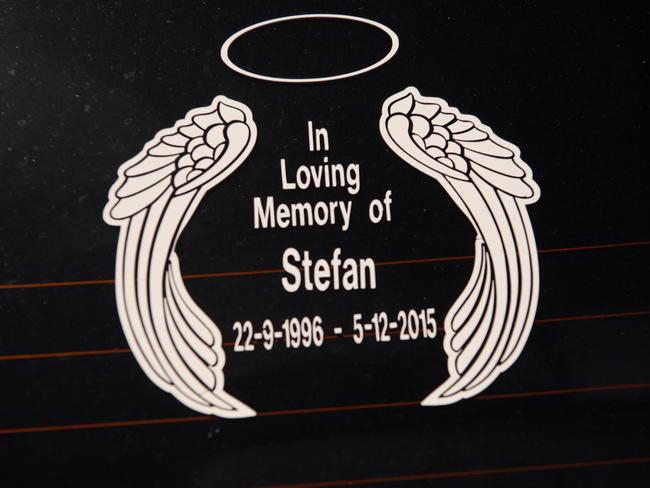

Julie Davis, the mother of Stefan Woodward, says she would do anything to hold her middle son one more time. Stefan died from a MDMA overdose at Adelaide’s Stereosonic music festival in December 2015.

Each night she walks into his room, sits on his neatly made bed and cries. Sometimes she slumps on the floor.

His room — untouched since his death almost four years ago — is a reminder of his passions, sporting achievements and what a “good bloke” he was. Some of his ashes are there alongside his favourite Stussy T-shirt. People think it is odd she has not packed up his things but grief plays tricks with her, like it does with the other mums.

“It took me two years to move his shoes out of the laundry” Julie says.

“I keep thinking he will come home and say: ‘Why are my shoes not in the laundry anymore?’

“That is probably one of the reasons why I haven’t changed his room. Because I think he will get mad at me if I touch or move anything.

“What if he does come home and ask: ‘What are you doing in my room?’ He didn’t like me in his room. A few people say you need to pack stuff away and that is why I am still upset.”

Julie, an aged care worker, 43, is still grappling with the reality that greets her on waking.

“Some mornings are better. But every morning I wake up and I go walk into his room. I see the sun shining through and I know he is not there,” she adds.

“He always had the blinds shut. One big foot sticking out the bed. He was very tall. Even with my highest heels I wasn’t taller than him. And then I just say: ‘Morning bubba’. I try and start the day, try and breathe and get to work.”

It was 40C on December 5, 2015 when Stefan went to the Stereosonic Music Festival, in Adelaide’s Bonython Park with about 30 friends.

He had taken an ecstasy tablet filled with pure MDMA.

Some of those “friends” pulled him out of a first aid line when he was feeling unwell but then left him to die alone next to a side fence.

Julie remembers returning from the supermarket to several missed calls from his mates. She remembers racing to the Royal Adelaide Hospital. She remembers believing authorities had the wrong person.

Julie sat at his bedside for more than 14 hours pleading with him to wake up. At 7am the next morning her worried husband and best friend pried her away to begin life without him.

What she also remembers is how her son died, alone, melting and knowing he was in trouble. The police inquiry remains open as detectives investigate a “person of interest”, a friend who they believe sold Stefan the drugs.

The loss of their child has invited depression and anxiety to lurk at the back door.

“I panic more that I can’t see him ever again,” she tells the Ripple Effect from her Largs North home. She is filled with regret and anxiety as everyday life triggers panic attacks — sunscreen, bacon, ambulance sirens, even driving past roadworks.

Julie had always warned him about being sun-smart. Stefan, a talented state lacrosse player who worked hard at the local Foodland, attended the popular music festival with 30 others, some of whom he had just met through a high school friend.

The following week he was going to start a plumbing apprenticeship on his path to a road construction career. Parked in the family driveway is his tiny white Daihatsu Charade he was about to drive. It now has a sticker in tribute on a window, just like all the family’s other vehicles — a gift from his step-grandmother.

At dinner the night before he died, he promised his mother he would only drink Woodstock bourbon and cola cans. He hated taking medicine tablets and was not into drugs.

Stefan, who had just finished year 13 at Seaton High School so he could start his trade, also promised to be sun-smart after being burnt at another festival.

On a searing summer day, his mother burnt her feet while hanging out the washing. So she messaged him to stay safe, drink water and that she loved him.

He replied that he would and that he loved her. It was their final words.

Ms Davis, whose mother Caterina died last year aged 76 from kidney and liver failure, remembers warning him about being sun-smart.

When she saw his body all she could smell was sunscreen.

“Now it is hard for me to smell sunscreen,” she says as she wipes away tears.

“I don’t like going to the beach because when I went to hospital … I went to kiss him and he smelt like sunscreen. It is a bad trigger.

“I try. I have been to the beach maybe four times. Only for Jayven (her youngest son aged five) because I feel like he deserves to see the beach.”

She is a different person from the fun-loving mother-of-three who trusted her middle son when he promised not to take drugs.

She has dyed her hair black, to reflect her constant dark mood, her arm is an artistic shrine to her son — the tattoo pain distracts from mental angst — and she struggles to cope with her emotions.

“You don’t think your child is going to die. I thought he was going to come back. I didn’t think he was going to die,” she says.

Despite her ongoing anguish, Julie keeps fighting for her family, who all miss their Stefan. While life is tough, she won’t give up on any of them.

For her American-born husband of seven years, former Naval Petty Officer Johnathan, 43, originally of Lima, Ohio, his US-based family has also been left devastated.

He just wants his “happy, smiling wife back” — for her eldest son Scott, 27 and for her youngest son, Jayven.

They talk about him, they mourn him, they remember the good times. Jayven talks to his big brother and shows him his drawings. His mother wants him to grow up knowing she loved Stefan and to never forget his face.

“First of all, I don’t think it is a ripple effect. I think it is massive waves and some waves are huge that almost kill me,” she sobs.

“Some bad days are really bad … and I have told my doctor this, I feel like I am getting worse. And he has told me, sometimes the third and fourth years are the worst. Especially when you lose someone so quickly. I am still in shock.

“I will never get over Stefan. He was my child. He wasn’t a plant that died. He was my son. I know he has died but I still look to the front door and I think he is coming home.”

She adds: “I don’t go out anymore. I am very fake at work, but I have to be. I try very hard not to take it to work. I am an activity officer where I have to make old people happy and play games so it is very, very hard. I can feel Stefan with me. Stefan would be upset with me if I quit. I just want to crawl into a hole … and cry. But I put my mask on and do my job. And hopefully don’t break down.

“When I finish work I sit in my car and cry because I got through it.”

If she could scream a message to young people it would be this: “You could die and then you are going to completely ruin everyone’s life. Your mum’s life. Your dad’s life. Once you’re dead you are dead. You don’t know what it would do. I hate every day. I am numb. I can’t smile, I can’t laugh. You will ruin your parents’ lives.

“You will ruin their life forever until they die.

“None of this ecstasy is safe. Don’t take the risk. Don’t. You won’t ever have a girlfriend or boyfriend. I will never have a grandchild from Stefan. He is never going to get married. He never got to see his 21st.”

Julie grapples with the added complication that he could have been helped. .

“(Witnesses) heard them calling him names,” she reveals.

“They called him pussy — something to get him out of the first aid line. He wanted help. He knew something was wrong. And that makes me really angry. Instead of helping him they took him out of the line.

“If only they didn’t pull him out. It haunts me. The what-ifs and the whys. Why didn’t they help him more? Why did he take it? Did he take it? He pretty much melted, which hurts, because he must have felt really awful.”

‘SOME BAD DRUGS’

Adriana Buccianti knows how Julie feels. Her son also died alone.

At 1.30am on January 29, 2012, Adriana woke with a start.

She would find out later it was the exact time her son Daniel, 32, died of a drug overdose at the Rainbow Serpent Music Festival in country Victoria.

Daniel had moved back in with her and they were very close. A few hours before he died, he called and asked her to come get him after taking “some bad drugs”. As she readied to head to the music festival two hours away, she rang back and he assured her he was “now OK”.

He died several hours later.

“I remember not having a moment to even think and when it was all over the funeral was over, I remember sitting in my lounge room thinking what happened to all those people who said they were going to hang around and then you realise when you have your first dinner on your own, you’re home on your own, it is you,” she says.

“I look at Daniel’s photos and think, a) where did the time go and b) did you even exist? Your brain plays some amazing tricks on you.”

Like Jennie, her brain told her Daniel had simply gone away on a trip.

“I would think: ‘Oh he’s just going to come walking through the front door, put his bag down and say I’ve just been away for a while’, and you know it is the furthest from the truth but it is just how your brain works,” Adriana says.

THE PHYSICAL TOLL

Just a few months after Daniel died, Adriana herself ended up in a coma for 18 days.

“Daniel died on the 29th of January and in August I just got this rash, then I had shingles, and I was taking antivirals but didn’t feel right, in the end I called an ambulance and ended up in emergency department at the hospital and woke up 18 days later,” she recalls, putting it all down to the stress of grief.

“I had N1H1 flu, I had chickenpox and a viral pneumonia. Oh definitely, I’d go to bed crying, wake up crying and having to work in the meantime. I would write in a book and cry and when I read what I wrote now, I was so broken, so broken.

“People don’t understand, it is something you live, you either live with it or let it destroy you, there’s not much in between.

“I remember in the early days just thinking I want to go with you, I don’t think I would have done it, because I still have a daughter and a granddaughter at the time, but when you go through this horrific pain, it is all about you.”

Like Julie Tam, she also had “grief brain”. As a social worker, she spent a fair amount of time driving and found she was getting abused on the road.

“I was distracted, driving too slowly, or veering and people would abuse me,” she says.

“I ended up making a sign “mum in grief” to put on the bumper and people would steer clear. I had that on my car for a good six months.”

THE BIRTHDAY

Jennie, Julie and Adriana agree one of the most confronting, confusing days after the loss of their child was the birthday.

Josh’s birthday fell just four days before Mother’s Day. The pain had Julie in free-fall, so she decided to literally throw herself out of a plane.

“I said we should do something out of the box, like jump out of an aeroplane,” Julie says.

So she and husband John did just that. They were joined by Josh’s cousin, uncle and one of his best mates.

The day Josh was born will always be celebrated Julie says, with something out of the box.

Jennie also felt compelled to celebrate what would have been Alex’s 20th birthday on May 25.

“We had a massive gathering …” she adds. “With 50 people over and we had a spit and all her friends came over. I won’t say it was an easy day, but the day she came to us, I will always celebrate that.”

Adriana celebrates as well with her friends and a chocolate mud cake, Daniel’s favourite. He died just nine days after his birthday, so the month of January is painful.

Adriana’s brother Bruno and his wife Sue know all too well the deep pain of losing a child. Their daughter Madelyn died of leukaemia in 2005.

She was only nine years old and she was close to her Uncle Dan. Each year, on Madelyn’s birthday, Adriana, Daniel and his sister Melissa met with Bruno and Sue at the cemetery to celebrate the day Madelyn was born. They have now stopped the tradition as Madelyn’s birthday is January 29, the same day Daniel died.

“The long term effect is we don’t have our nephew and it is a very bittersweet birthday for Madelyn now that we have Daniel’s anniversary of his death on the same day,” Sue Buccianti says. Another family Christmas tradition has also come to a halt.

“We all used to go over to Adriana’s to do Christmas together and Daniel, a chef, would cook. We’ve only done it once since Daniel died. Everything falls apart,” she says.

Adriana has also been a fierce campaigner for pill testing and, like the broader debate, there are opposing views in the family.

Daniel’s younger sister Melissa disagrees with her mother.

“We don’t talk about it, it’s so sad. She can’t talk about her brother without crying. It does divide families,” Adriana says.

ANOTHER HOT SUMMER

Jennie Ross-King has also taken up campaigning for more education and pill testing.

“As a parent, I want to be part of the education process. Don’t be as naive as I was, I don’t think I was that naive, but the kids think they know stuff but they don’t,” she says.

Julie agrees. She spends her days now working on a foundation she and Josh’s friends set-up to honour Josh. Called Just Mossin, Josh’s slang for kicking back, the foundation aims to education on the perils of drug-taking because Josh was “not a druggie”, he was an everyday young person doing what is so normalised in the music festival scene.

All agree, as the music festival season rolls into a long, hot summer, they want no other parent to go through this.

They each hope the pain of their loss can help change the world.

“I am a different person than what I was 12 months ago,” Jennie says.

“I believe Alex is with me and pushing me to make change and make a difference. She never liked to see someone in pain, or on their own.

“She bought out the best in people and that is what she is doing with me now so this doesn’t happen to someone else.”

Julie Davis pleads with those thinking of taking drugs, to think of their mums.

“Maybe they might not do it (and think) I love my mum.

“I would hate for my mum to cry every day. Because I cry every day.”

If you need help? Please call Lifeline Australia 13 11 14 — 24 hours a day, 365 days a year or in the event of a medical emergency, call triple-0 immediately.

Originally published as One drug. Four mums. Four dead children and the devastating ripple effect