A music festival, a drug, a dead teenager – now Stefan’s grieving mum warns others how one pill can kill you

Stefan Woodward won’t ever come home. At just 19, he died after overdosing at an Adelaide music festival — but every night his mum Julie walks into his room, sits on his bed and cries for her son.

The Ripple Effect

Don't miss out on the headlines from The Ripple Effect. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Julie Davis walks into her son’s room every night, sits on his neatly made bed and cries. Sometimes she slumps on the floor, unable to get up as a tidal wave of pain consumes her.

She fights insomnia as questions swirl in her head. And, if she does sleep, it is full of bad dreams before she wakes to a living nightmare that her music festival loving boy is dead.

Gone. Forever 19. Another tragic illicit drugs overdose statistic.

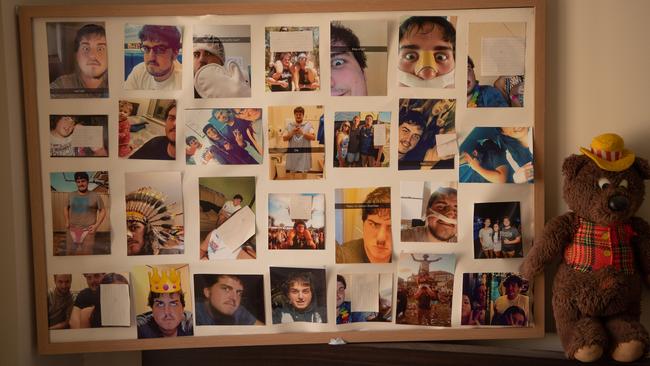

Each morning she returns to his dusty room, now a heartbreaking shrine to his life, untouched since his death almost four years ago.

Alongside his ashes and his favourite Stussy T-shirt are reminders of his passions, sporting achievements – what a “good bloke” he was.

She speaks to him, asking her kind, gentle giant of a boy to give her strength to face life without him.

In her mind, he replies how sorry he is for letting her down. And then the river of tears flow again.

Stefan Woodward, a larrikin teenager who worked hard and loved helping others, died at the Stereosonic Music Festival in Bonython Park, on Saturday, December 5, 2015.

He had just turned 19.

He took an ecstasy tablet filled with pure MDMA or methylenedioxymethamphetamine.

Witnesses reported how “friends” pulled him out of a first aid line but then left him to die, scared and alone, next to a side fence as temperatures soared past 40C.

Today, his bereft mother battles every parent’s worst nightmare.

She only leaves her western suburbs home for work. She can’t smile. She can’t be happy. She never goes to the movies or a restaurant. She is numb. Ms Davis, an aged care worker, 43, is filled with regret and anxiety as everyday life triggers panic attacks – sunscreen, hot weather, bacon cooking and ambulance sirens. Even driving past roadworks.

She is a different person from the fun-loving mother-of-three who trusted her middle son when he promised not to take drugs.

An empty shell of anger, heartache and never-ending questions.

She has dyed her hair black, to reflect her constant dark mood, her arm is an artistic shrine to her son – the tattoo pain distracts from the mental angst – and she struggles to cope with her emotions. Lost without her “shadow”, she would give up everything to hold him one last time.

“I panic more that I can’t see him ever again,” she tells the Sunday Mail, sobbing in her Largs North home that is filled with photos and reminders of her dear son.

“Every morning I wake up and I go walk into his room. I see the sun shining through and I know he is not there. He always had the blinds shut.

“One big foot sticking out the bed. He was very tall. Even with my highest heels I wasn’t taller than him.

“And then I just say ‘morning bubba’. I try and start the day, try and breathe and get to work. (I) say good morning to Stefan and say ‘give me strength to get through today’.”

COURAGE TO SPEAK OUT

Having grieved in silence for almost four years, she has courageously decided to speak out today, hoping she might prevent another bad decision.

Vehemently against pill testing, she worries young people don’t realise – or understand – the dangers.

“You could die and then you are going to completely ruin everyone’s life,” she says. “Your mum’s life. Your dad’s life. Once you’re dead, you are dead. I hate every day. You will ruin your parents’ lives. You will ruin their life forever until they die.

“I could never be happy. I can’t when my son is dead. How could I? I am very fake. I wear a mask now. People don’t want to know. Or they think I should be over it.

“But if I could talk to (those wanting to take drugs) I would say you don’t know. None of this ecstasy is safe. Don’t take the risk. Don’t.

“You won’t ever have a girlfriend or boyfriend. I will never have a grandchild from Stefan. He is never going to get married. He never got to see his 21st.”

Her words are especially directed at young people looking to experiment or facing peer pressure – the “just have one, you will be all right” mentality.

“You could die. There is that risk – you could die,” she says. “If someone hears how it totally devastates or guts you, or gives your family, especially your mum, brutal pain every day, they might stop taking it.

“Maybe they might not do it (and think) I love my mum. I would hate for my mum to cry every day. Because I cry every day. I am just so sick of crying every day. And I can’t not cry. I wake up and he is not here.”

FAMILY IN PAIN

Despite her ongoing anguish, Ms Davis keeps fighting for her family, who all miss their Stefan.

For her American-born husband of seven years, former Naval petty officer Johnathan, 43, originally of Lima, Ohio, whose US-based family has also been left devastated. He just wants his “happy, smiling wife back”.

For her eldest son Scott, 27. For her youngest boy, Jayven, 5. They talk about him, they mourn him, they remember the good times. Jayven talks to his big brother and shows him his drawings. His mother wants him to grow up knowing she loved Stefan and to never forget his face.

While life is real tough, she won’t give up on them. “First of all, I don’t think it is a ripple effect. I think it is massive waves and some waves are huge that almost kill me,” she sobs.

“Some bad days are really bad … and I have told my doctor this, I feel like I am getting worse. And he has told me, sometimes the third and fourth years are the worst. Especially when you lose someone so quickly. I am still in shock. “I will never get over Stefan. He was my child. He wasn’t a plant that died.

“He was my son. I know he has died but I still look to the front door and I think he is coming home. That is probably one of the reasons why I haven’t changed his room. Because I think he will get mad at me if I touch or move anything.

“What if he does come home and asks ‘what are you doing in my room’. He didn’t like me in his room.” This sparks a rare smile.

“I don’t go out anymore. I try very hard not to take it to work,” she says.

“I am an activity officer where I have to make old people happy and play games so it is very, very hard. I can feel Stefan with me. Stefan would be upset with me if I quit.

“I just want to crawl into a hole … and cry. But I put my mask on and do my job, and hopefully don’t break down. When I finish work I sit in my car and cry because I got through it.

“I don’t want any other parent to go through this pain.”

HE SAID HE WOULD BE SAFE

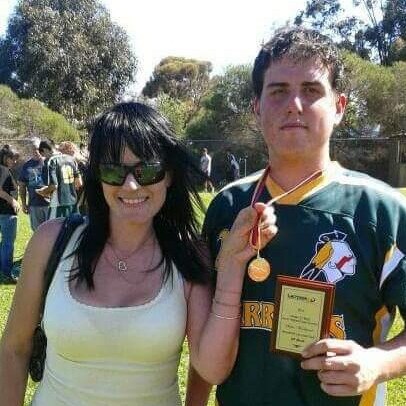

Stefan, a talented state lacrosse player who worked hard at the local Foodland, attended the music festival with 30 mates, who he had just met through a high school friend.

The next week he was due to start a plumbing apprenticeship on his path to a road construction career.

Parked in the family driveway is his tiny white Daihatsu Charade with a sticker in tribute on a window, just like all the family cars – a gift in death from his step-grandmother.

At dinner the night before he died, he promised his mum he would only drink bourbon and cola cans. He hated taking medicine tablets and was not into drugs. Stefan, who had just finished Year 13 at Seaton High School so he could start his trade, also promised to be sun-smart.

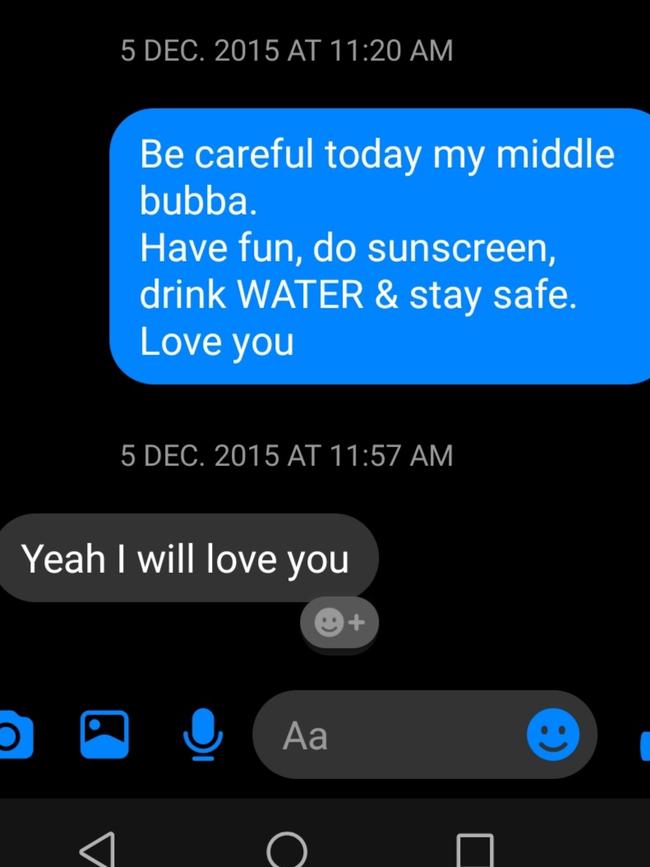

On that searing summer day, Ms Davis burnt her feet while hanging out washing. So she messaged Stefan to stay safe, use sunscreen, drink water and that she loved him. He replied he would and that he loved her.

It was their final words.

When she saw his body all she could smell was sunscreen. “Now it is hard for me to smell sunscreen,” she says as she wipes away tears.

“I don’t like going to the beach because when I went to hospital … I went to kiss him and he smelt like sunscreen. It is a bad trigger.”

The hours after he died are a blur.

She remembers returning from the supermarket to missed calls from his friends. She remembers racing to Royal Adelaide Hospital, and calmly telling police they had the wrong person. She held him for more than 14 hours pleading with him to wake.

At 7am the next morning her worried husband and best friend pried her away from her “beautiful son” to begin life without him. What she also remembers is how he died – alone, melting and knowing he was in trouble. Detectives are investigating a “person of interest”, a friend they believe gave him the drugs.

GUT–WRENCHING FURY

Ms Davis believes her son’s drink was either spiked by someone wanting a laugh to see him “wasted” or he gave in to peer pressure. Regardless, it sparks pure, overwhelming and gut-wrenching fury.

Her rage triggers violent thoughts – feelings she has shared with detectives, who tell her to let them hand out justice. So she patiently waits.

Police have told her their person of interest is “close to home” and has been in her house, but their identity is a secret. Detectives warned her against speaking to the Stereosonic “friends”. She can’t understand how they sleep at night. She hopes one day someone will get a conscience and tell police the truth.

“I am so angry with him (Stefan). But I not just angry with him, I am angry with his friends,” she says.

“Friends that I have been told have been in my house. Friends I thought really cared for Stefan.

“(Witnesses) heard them calling him names. They called him ‘pussy’ – something to get him out of the first aid line. He wanted help. He knew something was wrong. And that makes me really angry. Instead of helping him they took him out of the line.

“And they didn’t stay with him because he was found by himself slumped against the fence by a security guard, so I am just very angry at that because every night I have a lot of what ifs and whys.”

She adds: “Why didn’t I stop him going because it was so hot. Why did I let him buy that ticket? What if it was cancelled that day because it was so hot? What if his friends took him to the front of the line?

“If only they didn’t pull him out. It haunts me ... why didn’t they help him more? Why did he take it? Did he take it? He pretty much melted, which hurts, because he must have felt really awful. “The peer pressure thing is really out there. They called him names. They bullied him out of that first aid line. That kills me.”

But staring off into her garden filled with “Stefan flowers”, she looks back and pauses.

“It has ruined me,” she says.

“Some days I don’t even want to get up but I drag myself up. I don’t brush my hair. I don’t care how I look. I don’t give a s--- about anything anymore. I had him when I was 19. It is awful but he died at 19. I just want Stefan back.”

If you need help? Please call Lifeline Australia 13 11 14 — 24 hours a day, 365 days a year or in the event of a medical emergency, call triple-0 immediately.