When it comes to athletes achieving greatness in their profession, their family’s fingerprints are all over it | Graham Cornes

The world’s greatest sporting stars all started with ambitious childhood dreams to become the best, but they didn’t do it alone. For good or the bad, their parents had a huge hand in their success, writes Graham Cornes.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

What makes a champion? It’s an intriguing question, particularly for a parent who may have aspirations of greatness for their children.

Is it natural talent? Of course that’s important, but so many with natural talent fall by sport’s wayside.

Is it dedication to training? Definitely. Is it a love of the sport? Yes, you have to love it. Is it a willingness to accept instruction and criticism? Maybe.

Is it desire - is it important for a young child to dream of sporting greatness, to emulate their sporting heroes? Apparently not.

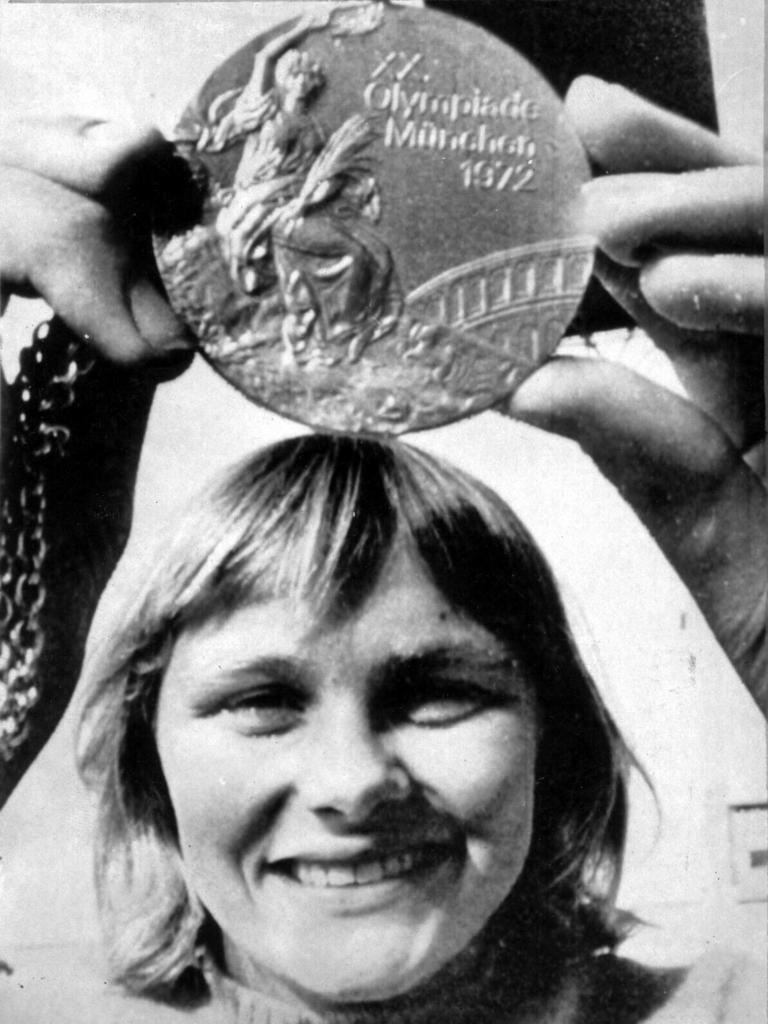

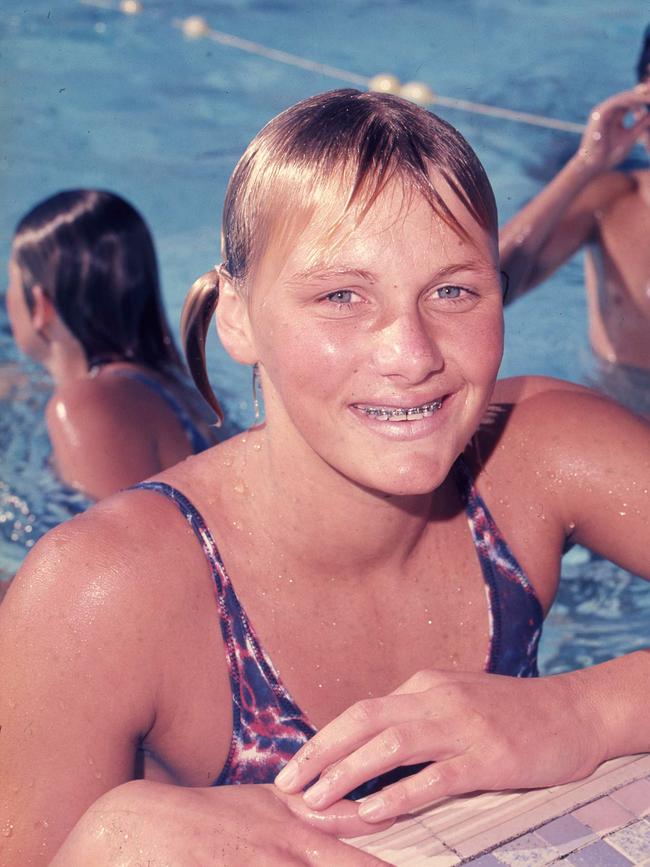

One of the most fascinating conversations that I’ve had recently was with Shane Gould, an Australian swimming legend. She was still only 15 when she won five individual medals at the Munich Olympics - three gold, a silver and a bronze. Then she retired, shunning the fame and the constant media pressures.

Her ideology on developing young champions, and achieving sporting greatness is interesting. The accepted mentality is that kids who have some talent for a sport dream of emulating their sporting heroes.

Don’t we think it’s healthy to have sporting role models? Not according to Shane Gould.

“I don’t think it’s right that a kid can say ‘I want to go to the Olympics when they are only nine or 10 years old’. It’s too far away. It’s unachievable at 10 years old,” she said.

Gould espouses the concept of setting immediate goals and training for something that’s immediately achievable.

“To feel satisfied and content, you have to have realistic goals that are achievable,” she said.

Surprisingly, for Gould, representing Australia at the Olympic Games was not a burning ambition nor is it a crowning achievement. She seems just as pleased with her under-7 school champion award as she is with her Olympic gold medals.

Gould has always seemed a reluctant hero, a spiritual being close to nature, who is oblivious to the adulation. Much of her childhood was spent in Fiji where her father worked for an airline company.

“I was a free-range kid who grew up around water”, she laughs.

Back in Australia she won a bronze medal in under-9 breaststroke championship and so came to the notice of swimming coaches. But still she hadn’t heard of Dawn Fraser – she knew vaguely of just one elite swimmer, Karen Moras, a 400m freestyle swimmer who had won a bronze medal in Mexico.

It was her parents, not swimmers, who were the biggest influence on her greatness.

“It’s the parents who entice children into sport way more than elite athletes”, says Gould.

And therein lies the key. The parents.

It’s true that before kids have any sporting interests, they will follow their parents. When they start to play sport themselves it’s generally the lead of their parents that determines the sport.

How much enjoyment did we get as kids watching our parents play? Was it football, netball, tennis or cricket? Those memories are etched forever.

Didn’t we want to be like them? In presentation speeches when a sportsperson is accepting award, the biggest influence on their career is often a parent. It’s the father (or mother) who spent endless hours kicking, catching or throwing.

But then, did we want to be like the sporting heroes we saw on television? How influential are they compared with parents?

In Gould’s case, her parents were supportive but not intrusive. They didn’t push. They did the running around for Shane and her sisters. There is the delicate balance been being supportive and pushing the kid too far, too soon.

Sam Konstas is Australia’s latest young sports star. Yes, he still has a long way to go but he will have a big future. Those who knew him growing up, tell the story of the kid who, from a very early age, would drag his father out of bed at 6am for endless net sessions.

How many parents would endure that? His father didn’t drive the passion but he was there to support with time, transport and endless throwdowns.

On any given morning you can drive past the lake at West Lakes and see the rowers training. Rowers and swimmers. Are there any more dedicated athletes?

And for every dedicated rower or swimmer there has to be a dedicated parent who has sacrificed sleep and time to get the kid to training.

Olympic cycling champion, our own Anna Meares, tells of the sacrifice her parent made with a weekly 600km round trip to MacKay and the nearest velodrome. Fifteen year-old Mark Ricciuto’s dad would drive him down from the Riverland for training at West Adelaide.

There are so many similar stories. Unfortunately there are probably more stories of parents who couldn’t afford the time or the expense to support the sporting ambitions of the children. However, there is always a contradiction.

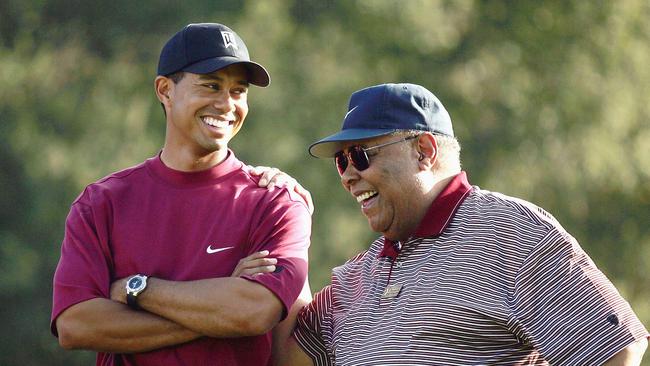

Unlike Shane Gould, whose sporting ambitions looked no further than the next contest, there are many successful champions who were driven by the ambitions of their parents. Tiger Woods, the Williams sisters and even our own Lleyton Hewitt owe their success to the drive of their parents.

The tough love didn’t break those champions. But tough love isn’t for everybody, particularly in this age of entitled youth.

Gould’s philosophy of minimalistic goal setting and not having role models can be debated. I’ve written before of the journey of Sam Smart, who was on one of the Crows’ early lists. How, as an 11-year-old kid in a country town, he set his goals on playing for Norwood and graduating as a doctor. How he studied to get a scholarship to one of Adelaide’s private schools. How he worked year by year towards those goals. How he did play for Norwood. How he eventually became a doctor.

I never tire of telling the story. Those early goals drove him.

Then there are others who achieve against all the odds of dysfunctional family environments and abject poverty. Look no further than the inspirational stories of Youth Opportunities, a charity supported so generously by Adam Scott. A young person gets an opportunity, is supported and achieves education levels wildly beyond any early expectations.

It is not a sporting charity but the message of achievement should inspire any athlete.

Shane Gould feels that a young sportsperson should be inspired by the activity.

The goals should be intrinsic: “What does it feel like, how can I get better, fitness and health.”

She shuns extrinsic goals like medals, rewards and travel, but one can’t help feel that she has been hurt somewhere along the way.

“Fans are fickle, fame is fleeting,” she says.

Who are we to argue with an Australian sporting legend, but why not let the kids have their role models and their sporting dreams?

And if they do start to show potential, as Shane says, then break those dreams down into achievable next steps.