The game of cricket used to be romantic, but nowadays that has all but faded away | Graham Cornes

From the simple old days to the modern day proliferation of contests, styles and differing formats. Cricket used to be a romantic game, writes Graham Cornes.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Cricket used to be a romantic game. The romance has faded now, eroded by the proliferation of contests, styles and differing formats.

It was simple in the old days. We followed state-based Sheffield Shield cricket and we followed the Australian test team.

Sheffield Shield cricket was exciting because the great players competed. The best Australian cricketers played in the Sheffield Shield competition. There was no resting them before the Test matches.

Maybe nostalgia enflames the romance but really, who of the current Australian players could be described as the romantic Test hero? Consider.

Was there a more romantic cricketing hero than Keith Miller? Ridiculously handsome with that mane of jet-black hair tossed back, he played the game with a swashbuckling intent and the derring-do of one who had risked his life flying Spitfires in World War II.

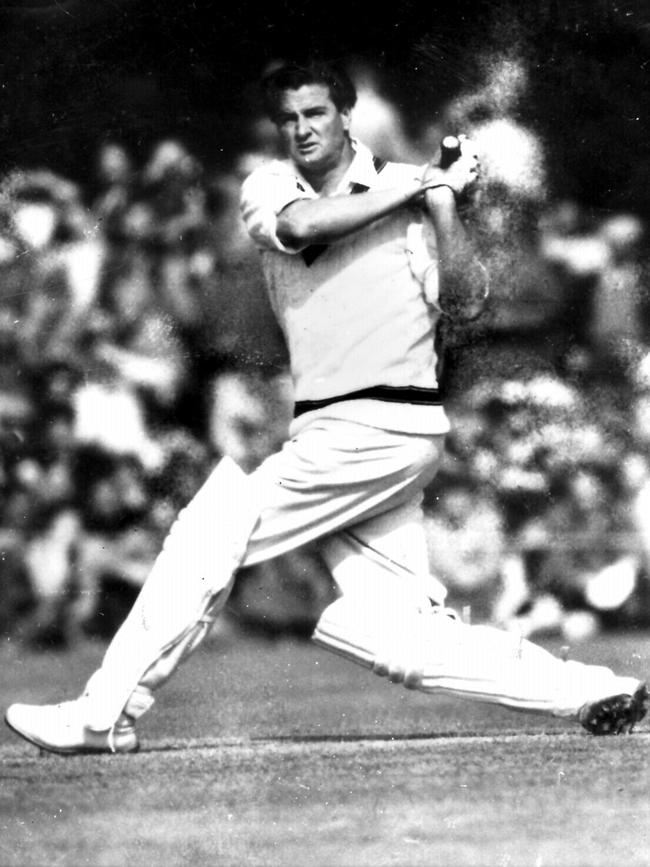

Has there been a more elegant Australian batsman than Greg Chappell? Dennis Lillee’s run-up and action was captivating, seductive even. Their performances exuded romance.

Sir Donald Bradman played 62 Sheffield Shield matches and averaged 110. He would never be described as romantic but he was the best ever and the sheer weight of runs commands reverence.

Incidentally, according to the ESPN Cricinfo website, only two other batsmen have averaged over 100 runs in Shield cricket. New South Welshman Owen Rock averaged 112, two more than Bradman.

A veteran of the First World War he graduated as a doctor. Consequently his medical career took precedence and he played only four matches.

Barry Richards thrilled South Australians in the eight games he played in the 1970/71 Shield season. He averaged 100.09. But Bradman’s average survives the scrutiny of longevity.

Over the decades, we’ve always been able to go to Adelaide Oval to see these great players play in Shield matches. Ian Chappell captained the team that won the Shield in 1975/76. Hookesy captained the team that won in 1981/1982. Darren “Boof” Lehmann captained a team which included Jason Gillespie in 1995/96.

How many of today’s kids can go to a Sheffield Shield match and watch their Test heroes? The childhood memories of seeing them in action stay with you forever.

I was 11 in 1959 when I saw the great Ray Lindwall bowling for Queensland against South Australia on the Adelaide Oval. He wasn’t a tall man but he had a beautiful fluid action. He took 7/92 that day.

My grandmother, who aspired to a higher social status than the union with my grandfather, a farm labourer who had been wounded at Gallipoli, suggested, was a member of the MCC.

Accompanying her to the MCG to see Bill Lawry open the batting for Victoria is a permanent memory.

True, there was no romance in that innings. “Stolid” is a better adjective but at least I saw the legend in action.

Kids don’t have the same opportunity to see their heroes live today. When the stars played in Shield matches they were accessible. Not now.

Perhaps it was inevitable but after Kerry Packer and World Series, cricket was not the same. Even Test cricket is different.

Here in Adelaide we are in the middle of a Test match that is being played half during the day in natural light, and half at night under artificial lights. It’s a Test match that is dependent on when you bat, not on which team has the superior talent.

Then there are the one-day international matches and the T20 series played at all corners of the cricketing world. Different skills are required for the various formats. A great Test player might struggle in the short form of the game. Conversely, a young player like Jake Fraser-McGurk, who can’t get a game in his Sheffield Shield team, will earn $1.6m for a seven-week IPL season.

It’s further complicated by the fact that not all formats of the game are accessible on free to-air television.

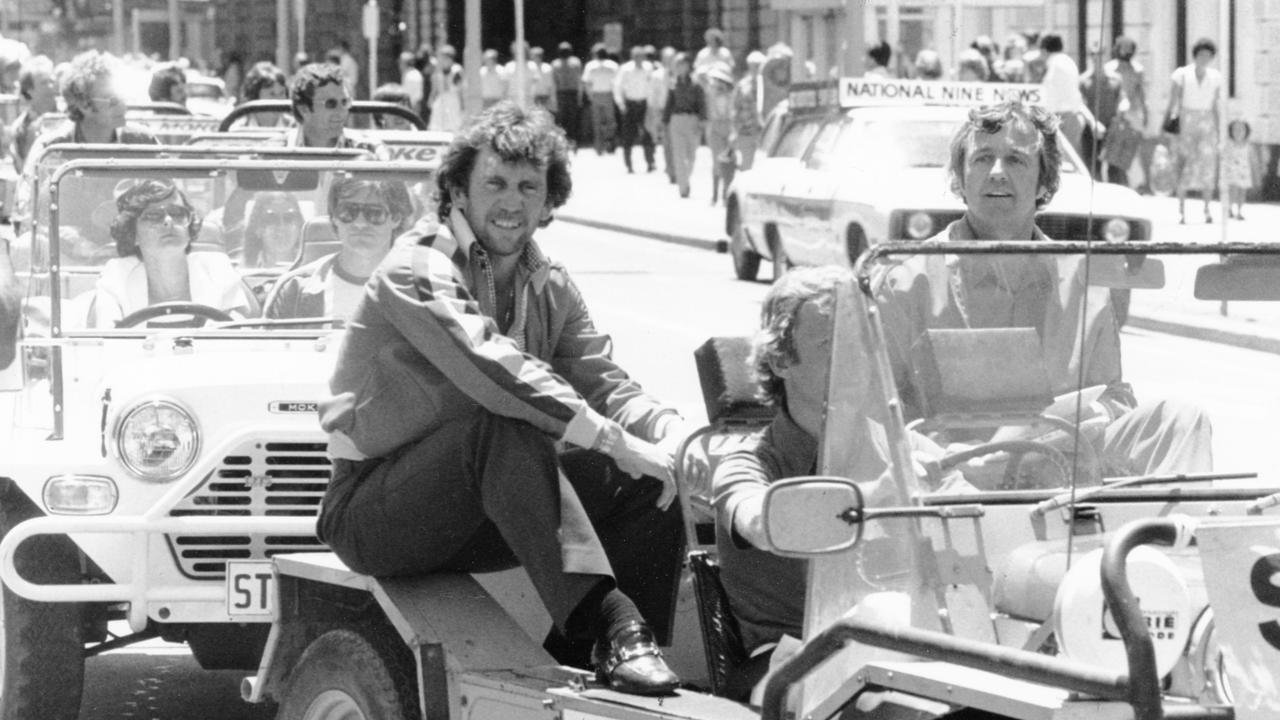

I dined this week with Ken Cunningham and Bruce McAvaney, two iconic South Australian sporting personalities. “KG”, the former umpire, Sheffield Shield cricketer and pioneering sports/talk broadcaster, and McAvaney the unsurpassed commentator whose depth of sporting knowledge is legendary.

In such company, you don’t talk, you just listen. Obviously, as they laughed and talked, the topic of cricket was foremost.

I’ve worked with KG for nearly 30 years now. I doubt there is a more frustrating person to work with – for this one simple reason. His level of self-deprecation is intolerable. Modesty is one thing but there comes a time when you have to recognise your achievements and accept the compliments.

KG refuses to accept his role in those great South Australian Sheffield Shield teams of 1963/64, 1968/69 and 1970/71. He deflects the compliments with mumbled comments: “I was lucky”, or “I was just an average player”, or “I was lucky to play in a great era”, or “How blessed was I to play with those other great players”.

He is right in one respect. He did play with some great players. Maybe nostalgia can distort reality but after the West Indies tour of 1960/61 when television brought the game into our loungerooms for the first time, it was cricket’s finest era.

McAvaney was having none of KG’s modesty. “There weren’t too many better number six or seven batsmen who could also bowl”, said the guru. “A 37 average means that if you made a duck or a low score, you had to make 70-odd the next time.”

It makes sense. And there was this one little snapshot of his bowling which admittedly was restricted by playing in the same teams as Ashley Mallett and Terry Jenner. In a 1969 Shield game against New South Wales at the SCG, KG took 3/16 off 9.4 overs.

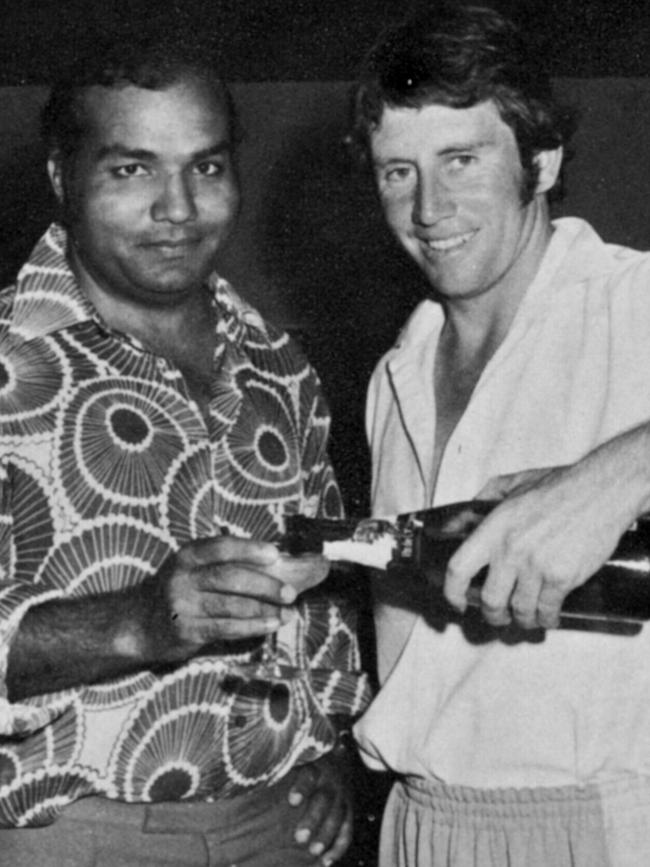

As a bowler, he was “handy”. But KG is also right. He played with some great players. None greater than Sir Garfield Sobers who scored more runs and took more wickets than any other Shield player in that glorious season of 1963/64.

Then there were the Chappell brothers, and Les Favell, the captain about who he talks with unbridled reverence.

Ian McLachlan, who should have played more Test for Australia, Mallett, Neil Hawke and Richards who, but for the restrictions of the South African apartheid bans, would have been one of the greatest ever, were great players.

Unfortunately, time does not stand still and as much as we love the memories, we can’t live in the past.

It was unthinkable 60 years ago but India is now the leader in this New World Order of cricket. The sheer weight of population and the programs that they have in place to discover and develop junior talent, will ensure that dominance.

Sadly, it will come in a new form. The shorter formats of the game satisfy a younger population’s quest for instant gratification.

Unfortunately however, there is no romance in instant gratification.