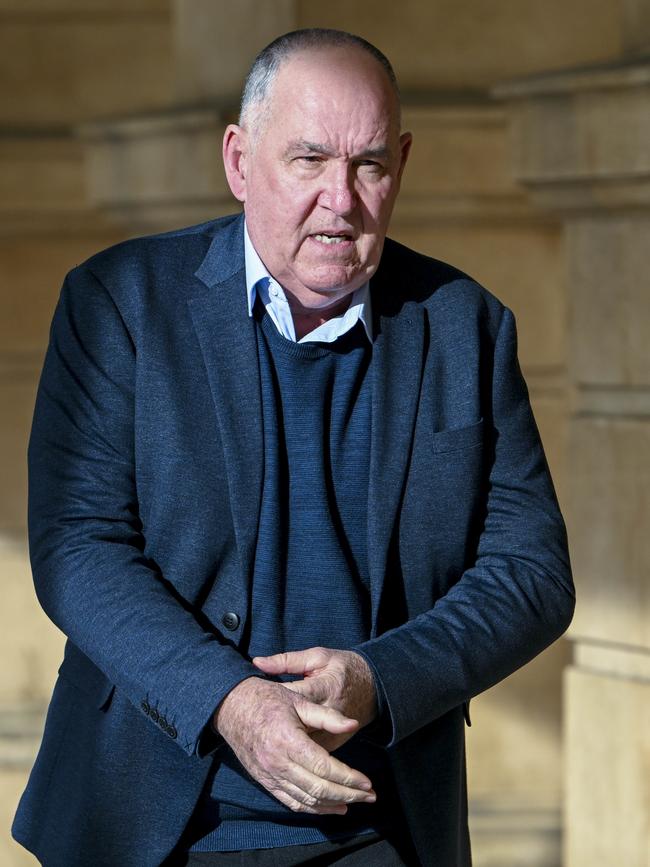

The Bicycle Bandit has given South Australians some serious thinking to do | David Penberthy

I’m not sure I want to be in the camp of those wishing a long, slow death on anyone, writes David Penberthy.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Those of us who are not religious – which in Australia these days means most of us – struggle with the concept of the deathbed confessional.

It all seems a bit cute and convenient that someone can spend their life making bad choices – repeated, conscious decisions which cause hurt to others – then neatly tie up their affairs with an 11th-hour chat with their chosen deity.

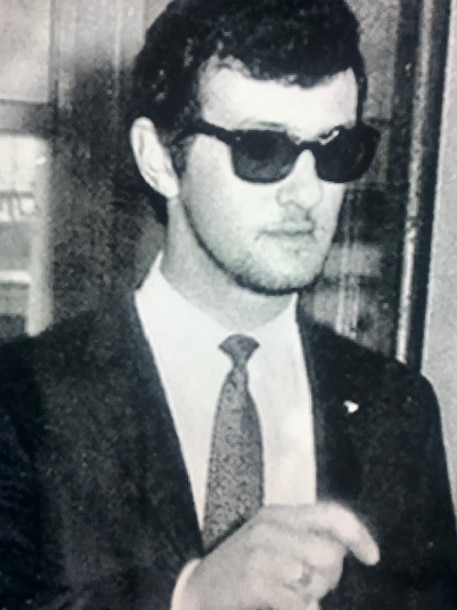

In the case of Kym Allen Parsons, better known as the Bicycle Bandit on account of his decade-long bank robbery spree during the 2000s, God had better free up his schedule to hear the full account of this man’s wrongdoing.

And if I were God, I’d be tempted to look the other way at my congested Outlook calendar that day, and focus instead on giving succour to children with cancer or people dying simply of old age after a life spent working hard and paying taxes, rather than clearing the diary to indulge a bloke who took the bludger’s path of sticking guns in women’s faces to make a quid.

Parsons’ moral reckoning was a very long time coming.

As my friend and colleague Sean Fewster quipped to me this week; “At least the mafia go to the confessional once a week”.

Parsons saved it until the very last, knowing the end is nigh as he confronts a terminal cancer diagnosis.

The really interesting dimension to the Parsons case is that he has also managed to ensure that his exit from this temporal world is as painless as possible via South Australia’s voluntary assisted dying laws.

This has proved a hugely contentious development, after its exclusive revelation by reporter Dasha Havrilenko and the aforementioned Fewster two weeks ago.

A key fact surrounding this revelation was that Parsons had applied for and sought permission to end his life under VAD before he made amends for his crimes in a legal sense by pleading guilty to 10 counts of armed robbery and one of attempted armed robbery.

That fact should not be construed as either of a criticism of the health system or the legal system. In this case, there would have been no visibility between Parsons’ status as a serious alleged criminal awaiting trial, and a citizen facing death from cancer with all the medical opinions to prove it, the key criterion for securing approval for VAD.

A generous-hearted person would argue that there should be no such visibility and that they should remain separate issues.

Not all of his victims see it that way.

As Fewster and Havrilenko reported, the fact that he was in possession of a VAD kit and had approval to use it caused a high degree of consternation among some of those who had come face-to-face with Parsons during his bank-robbing spree.

An anonymous source with insight into Mr Parsons’ circumstances said he felt “disgusted” that individuals facing charges were granted voluntary assisted dying packages before a trial”.

“What I am wanting to know from lawmakers and politicians is: Should this be allowed for before there is a trial?” he said.

It is an excellent question.

I would say that the answer to it should be “no”.

Let’s leave God out of it here. If a person has not made amends with their wrongdoing in a legal sense in the temporal world, why should they be afforded the luxury of dying the death they choose when they have failed to acknowledge the impact their own conduct has had on others?

In the absence of his subsequent guilty plea, Parsons’ attempt to access VAD could have been seen as the coward’s option, a way of avoiding not just the hardship of a painful death but also the hardship of a trial.

Even though the authorities put the cart before the horse by giving him VAD approval prior to his guilty plea, I would say that that in the event of him having pleaded guilty, apologised, and offered to repay the $350,000-odd he stole, it is easier to accept the fact that he has been given approval to end his life in the most dignified and painless manner possible.

Where this question becomes more morally challenging involves crimes involving the ultimate act of cruelty, the taking of another life.

On this question, the Parsons precedent means the state government and we as a community have some thinking to do.

To start with the two worst offenders in our prison system, what if John Bunting or Bevan Spencer von Einem fall terminally ill?

There are in fact suggestions that von Einem is very ill, possibly terminal, a fact which a sister of a victim of the Family killings raised with 7News just two nights ago.

Should people who have killed anyone, let alone taken part in the most sickening criminal enterprises in the history of this state, be given the right to choose their own death, the very right they denied to others?

It is on the face of it enraging to think of such a scenario.

But it remains morally complex. The old saying that you should never wish death upon anyone is a good one. It is one we should strive to live by, even though in the aforementioned cases it is hard to muster anything in the way of sympathy.

I am not sure I want to wind up in the camp of hoping that someone dies a long and slow death.

There is something medieval about it. It demeans us all. Perhaps extending a skerrick of sympathy to the very worst of the worst makes us even better people.

It is a fascinating case.

To end with one other theological question related to the deathbed confessional.

Does an 11th hour tell-all with the Big Guy upstairs actually guarantee you a spot in heaven, and spare you eternal hellfire?

Is it really that easy? I’m just asking for a friend.

He’s been a journalist for 32 years and has a bit of explaining to do.