South Australia’s South East farming communities split as rare earths discoveries bring major change

For more than 100 years, these have been farming communities but that could be about to change, writes Jessica Adamson.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The historic Joanna Community Hall, 330km southeast of Adelaide, has stood proudly for almost 70 years, surrounded by rich farming land and vineyards.

A portrait of Her Majesty, the late Queen Elizabeth II, still hangs on the northern wall.

No one has got around to replacing it with King Charles yet.

Joanna Hall’s played host to thousands of birthdays, weddings, concerts and fundraisers over the years. If the walls could talk, they would speak of true community connection and celebration.

But last Wednesday night, a more sombre group gathered there, a collection of farmers, vignerons and local business leaders with a fight on their hands.

Many are deeply concerned that their prime agricultural land has caught the eye of ASX listed exploration company, Australian Rare Earths or AR3.

For four years now, the company has been drilling on farming properties, in forestry plantations and along roadsides throughout the region.

What they’ve found is in global demand and potentially very valuable.

AR3 CEO Travis Beinke says it’s a significant discovery.

“Minerals found at Koppamurra in the South East, neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium, are critical to the energy transition,” he says.

“These rare earths are vital in the production of electric vehicles and wind turbines as we move towards a more sustainable world.”

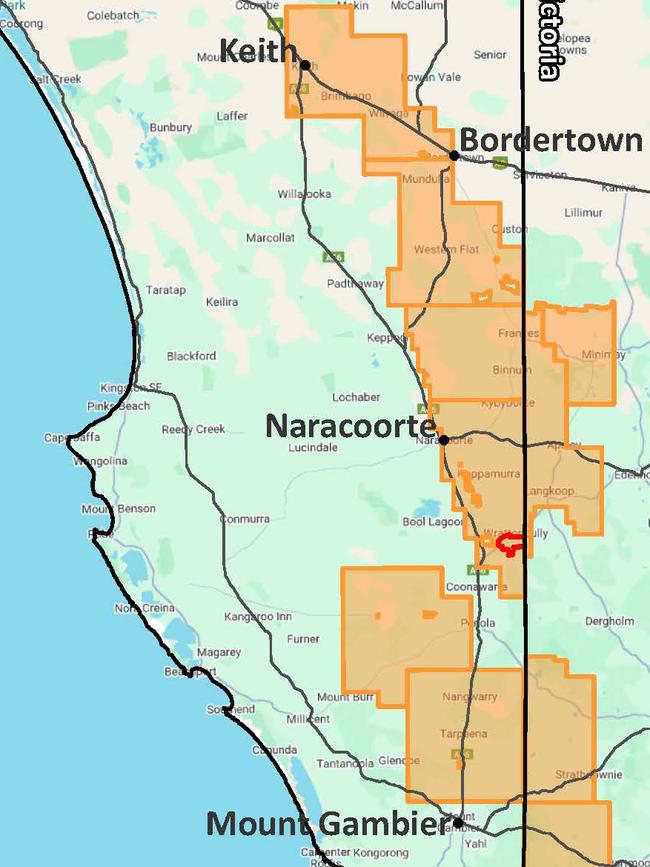

AR3 has been granted 10 exploration leases by the state government spanning more than 7000sq km from Keith to Mount Gambier and into Victoria. It’s known as the Koppamurra Project.

Right now, they’re preparing an application for a mining lease within it, an area of 20sq km southeast of Naracoorte.

Rare earths are also used in mobile phones, computers, vacuum cleaners and electric toothbrushes, along with medical equipment like MRI machines.

AR3 wants to sell them to the world and it makes some economic sense given that, until now, those highly sought after elements have only been produced in China and Myanmar.

The problem is, getting to the clay-hosted minerals means everything on top must go – irrigation, bores, fencing, sheds, soil and subsoil, maybe even the vineyards and centuries-old gum trees – if permission is granted.

AR3 promises to quickly rehabilitate the land, but right now, no one knows the long-term impact the process will have on this pristine and highly productive land, its soil, underground water and rich red gum landscape.

Finding out is a work in progress and that’s what’s causing community division.

Ken Turner lives within the proposed mining lease area. He and his daughter Nicola work the land.

“I’m one of those blokes prepared to sit back and wait until there’s an application,” Ken says.

“They’ve got to demonstrate before I support the mine that they can rehabilitate the land, the soil, our infrastructure and the water. You can’t fix it if they bugger it up.

“I think it’s good that we have the debate because I don’t want to see my daughter in 20 years’ time still being in limbo and not knowing whether they will mine or not mine.

“If we have the debate now, if the company lodges their application and the government assesses the soil, land and the water, they might determine that AR3 can’t mine there and then they all go away and leave us farming happily ever after.”

That’s exactly what many in the region are hoping for.

The newly launched Limestone Coast Sustainable Futures Association sees the project as one of the greatest economic, environmental and social threats ever to face community.

And while it might sound like a case of “not in my backyard”, the Limestone Coast produces the lion’s share of the state’s forestry and logging products, around half of our milk, potatoes and beef and a third of our wine and fine wool.

For generations its people have farmed one of the finest food bowls in the nation and they’re rattled by plans for a multi-generational mining project to run through it.

Limestone Coast Sustainable Futures Association’s chairman, Wrattonbully livestock producer Todd Woodard, says a lack of scientific evidence about the long-term impacts is fuelling concern.

“This is not an anti-mining campaign,” he says.

“We recognise the need to source rare earth resources for our clean energy transition. But it should not come at the expense of our food and fibre security and the hundreds of businesses and the value chain that this sector supports.

“Our prized agricultural landscape is one of South Australia’s greatest assets – an economic powerhouse generating more value per hectare than anywhere in.

“Unfortunately, recent history is littered with examples of malpractice and irreparable damage from strip mining activities leading to devastating environmental and social outcomes for Australian regional communities.

“We cannot risk irreparable damage to occur in our state’s food bowl. Our high-value agricultural land and key environmental assets must be protected for future generations.”

Committee member and farmer Dee Nolan says the region’s reputation, rated as one of the most reliable and high-value agricultural regions in Australia, is at stake.

“Then there’s the risk to our valuable underground water supply,” she says.

“People are very worried about the proposed use of acid to extract the rare earth minerals and the chance of it leaking into the aquifer.”

Ken Turner agrees that protecting the underground water and the 300-year-old red gums it nurtures is a priority.

“There’s an old adage that water is for fighting over and whiskey’s for drinking,” he says.

“I’m not convinced that small scale mining can’t occur, but the Landscape Board has a responsibility to manage the environment and save those trees, as they do with the water.”

Despite the community angst, Travis Beinke says AR3 is pushing ahead, confident the project will meet the required expectations.

“AR3 is proposing a progressive heap leach and rapid rehabilitation development

pathway enabling the return to farming to the land in a much shorter time frame than

traditional mining practices,” he says.

“Our studies must demonstrate no negative impact on groundwater or soil. If we cannot do this, we simply will not be granted a mining licence.”

They’re unashamedly working to get locals on side with a partnership-for-progress

philosophy, sponsoring organisations like Scouts SA, the Lucindale Camp Draft, the Naracoorte Horse Racing Club, schools and the local art gallery.

“AR3 has a vision to build a new industry with the local community for the benefit of the state while helping Australia secure supply of critical minerals that are in demand and essential to the clean energy transition,” he says.

Ultimately, the state government will decide whether mining and agriculture can successfully coexist in a region that brings us some of the country’s best meat, milk and vegetables, world-class wine and the timber framing for our homes.

The decision lies with the Department of Energy and Mining and it must get it right.