Sean Fewster: Continued debate over paroled child sex offenders shows inadequacies of both the law and society’s approach to the problem

AN “uncontrollable” child predator is set to be released. Legal authorities are attempting to mitigate the risk but the public is furious. This whole messy situation reveals serious problems with our approach to community protection, writes chief court reporter Sean Fewster.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

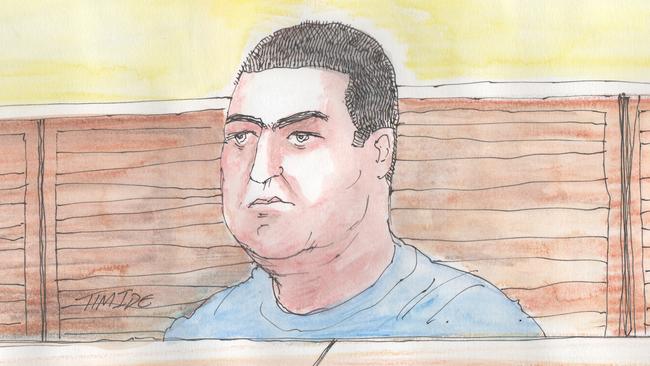

- Colin Charles Humphrys: Serial predator freed to Bowden-Brompton

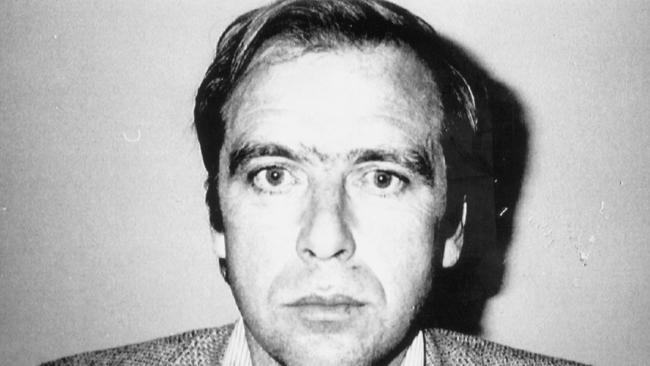

- Mark Trevor Marshall: “Risky” pervert’s bid for freedom rejected

- Gavin Shaun Schuster: Court intervenes to stop paedophile’s release

- The law: Read the legislation that governs the freedom of predators

- The decision: Judge explains why Humphrys will be released

PEGGY Fulton Hora — legal innovator, retired US judge and former SA Thinker in Residence — could sum up her opinion on criminal justice in a single line.

“If they’re bad, jail ’em and if we’re mad, rehabilitate ’em,” she would say.

Prompted to expand on that, Her Honour would say jail should be reserved for the worst of the worst, the criminals who simply could not function in normal society.

Those who could function, she would argue, ought to have the opportunity to make amends — regardless of how angry, upset, frustrated or even scared they made the community feel.

With his five-state, three-decade history of heinous child sex offending, predatory kidnapper Colin Charles Humphrys falls unquestionably into the first of Judge Hora’s categories.

The problem, however, is that our laws require judges to balance the second of her categories — rehabilitation — against public safety.

Section 24 of the Criminal Law (Sentencing) Act (1988) copped quite the beating over the final years of the Rann/Weatherill era.

Depending on whom you asked, it either gave too much weight to offering sex predators a second chance, or gave too little thought to terrified parents and vulnerable children.

It was another of Humphrys’ odious breed — serial offender Mark Trevor Marshall — who prompted change, thanks to his incessant attempts to be free.

Twice, authorities found child exploitation material in his prison cell just weeks after he filed a release application.

And yet that was not enough to stop him, because doctors feared his post-traumatic stress could not be addressed in custody and he was at risk of institutionalisation.

In concert with the then-Opposition, the former State Goverment tightened the laws by making public safety the “paramount consideration” in applications for release.

It also listed 10 other criteria that must be satisfied before a habitual offender could be considered safe enough to be allowed, under supervision, back into the community.

Those changes did little to stop Gavin Shaun Schuster, another monster who came within a hair’s breadth of moving into an address at Kilburn.

Schuster — whose crimes date back to his own adolescence — was set to live just a few hundred metres from schools and playgrounds.

Now-retired Justice John Sulan conceded Schuster would “always” be a risk but said “nothing is perfect in this world”, ordering release to stave off institutionalisation.

Prosecutors appealed and the Full Court overturned the decision — but said Justice Sulan was not technically at fault.

Instead, it ruled prosecutors had failed to demonstrate how easily Shuster could slip through his monitoring conditions, meaning the decision was made on insufficient information.

It is important to keep Marshall and Schuster in mind when considering Justice Trish Kelly’s ruling on Humphrys.

Like his grotesque peers, Humphrys is said to be in danger of institutionalisation, at a high risk of reoffending and either unwilling or incapable of controlling himself.

Unlike Schuster’s case, the court heard extensive evidence from psychologists, the Parole Board and the Department for Correctional Services as to how he could be supervised.

Weighing that volume of evidence against the risk to the public, Her Honour was satisfied that — as per the legislation — Humphrys could and should be managed in the community.

She also went a step further, saying Humphrys had yet to be given a chance to prove he could obey conditions and abide by supervision — another factor in favour of release.

“I do not consider that the point has been reached that it is yet appropriate to incarcerate him in all probability for the rest of his life,” she concluded.

Many in the public would disagree — still more would argue Humphrys has reneged on every “second chance” he has been offered by returning to his predatory ways.

Worse still, each and every one of those “personal failings” has destroyed the life of another innocent boy and ruined another family.

If Marshall showed the flaws in the law, and Schuster in the approach of prosecutors, the Humphrys case demonstrates how much more needs to be done to combat this problem.

Like it or not, criminals — even the bad ones — cannot be locked up, key thrown away, for the rest of their lives.

And if they cannot remain in our overcrowded prisons or bursting-at-the-seams mental health facilities, thought and resources need to be directed to alternative, specialist, secure housing.

It is not good enough to say “nothing is perfect in this world”, and it is unacceptable to have to release a dangerous felon who is “as good as he will ever be”.

Even further legislative change, as flagged on Wednesday by new Attorney-General Vickie Chapman, is but another band-aid on this open wound.

If they’re bad, jail ’em and if we’re mad, rehabilitate ’em — but we should be doing so in true safety, not on the weight of probability and chance.