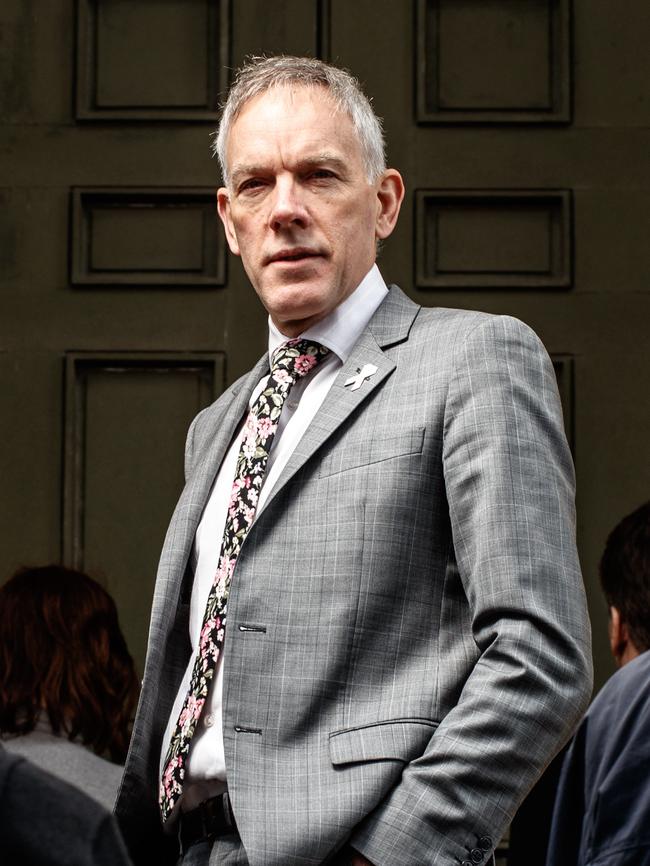

Michael O’Connell: Victims’ rights must be taken seriously when they enter the courts

DESPITE the remarkable improvements, some public officials, among others, still treat victims of crime ambivalently, writes Michael O’Connell.

- Prisoners taunting victims with misinformation about their crimes

- Michael O’Connell driven to make a difference to voiceless victims

IT’S Saturday afternoon or perhaps Tuesday night. When one is on call 24/7, days often blur.

Whichever day, the caller is a police victim contact officer.

“Sorry to disturb you,” they say, “We need your help again. Someone’s been killed. Can you arrange a homicide crime scene clean-up?”

After a briefing, I contact forensic crime scene cleaners. Respectfully, among many other improvements in victim assistance in the past decade or so, victims’ families are no longer left to confront such horror.

It has become one of my regular tasks.

Other changes include expanded services for women and children who are victims of domestic violence which include a dedicated legal service run by the Legal Services Commission and court assistance program run by the Victim Support Service.

As safety for these victims is paramount, laws have been reformed and initiatives introduced such as the family safety framework and Stay Home Stay Safe programs.

Money paid from the Victims of Crime Fund has helped employ specialist child witness assistance officers in the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions and to establish a victim register in Forensic Mental Health Services. These services have allowed victims of crimes perpetrated by mentally incompetent offenders the chance to more readily exercise their right to be kept informed on an array of matters.

My functions have evolved so I now help not only victims of crime that happens in our state, but our citizens who become victims of crime in other places, including overseas.

I have unfortunately become adept at repatriating victims of homicide from across the globe back home to our state.

All reasonable steps are taken to ensure these victims are returned with respect and dignity to loved ones.

On many occasions I am the public voice of victims. This often brings me into the media spotlight. It is important that victims are heard. It was once a cliche to say victims are the forgotten people.

They are no longer but victims still are not accepted as genuine participants in the criminal justice system.

Moreover, sceptics still try to push back. I have lost count of the number of times victims ask: “Why can’t I have a lawyer representing me in court?” Our system doesn’t allow it — yet. Victims do, though, have several participatory rights and that creates obligations on public officials.

Should a victim approve, I can exercise these rights for them, which I do either in person or through legal counsel. Pleasingly, some lawyers have embraced the concept of an equitable criminal justice system.

Lawyers now help victims be heard on charge bargaining; to apply for suppression orders; to deal with argument on competency and compellability to give evidence; to make impact statements; and, to make submissions on applications to revoke or vary intervention or mental health licence orders.

My job is unique in many ways. Our state was the first in Australia to appoint a Commissioner for Victims’ Rights and continues to be the only state with a commissioner who holds such extensive powers; likely, the only unparalleled in the world.

South Australia has been at the forefront of victims’ rights for decades and victim assistance have evolved. In some important areas, however, our leadership has waned.

The essential direct help provided by victim services is fundamental to supporting victims of crime in our state.

Their work is of huge value and importance; yet, annual grants from the Victims of Crime Fund have not increased adequately to allow these services to match all victims’ needs.

We also continue to face challenges in providing support for victims across a wide range of circumstances, such as those living remotely as well as culturally competent services to mirror the diversity of our society.

Rather than service delivery, the focus these past few years has been on the maximum payable for state-funded victim compensation, which is now $100,000.

Consequently, in law there is a possibility that victims of violence will be paid lump sums nearer to the estimated $88,000 in expenses such victims can incur — but few victims receive near maximum payments.

Further, the $100,000 is shy of the $150,000 maximum the Royal Commission recommended for the national scheme for victims of sexual abuse in institutions. Both sums are significantly more than the maximum ($50,000) offered to these victims under the redress scheme in our state.

While transforming justice is well underway and some victims have benefited, not all have. On a practical level some cases are resolved quicker in the Magistrates Court but there is no witness assistance service in that jurisdiction so, as more victims of serious offences come before it, they are denied important court preparation.

Victims are entitled to access to justice at all times but still too manyfeel they have been denied justice. Such sense of justice is not solely about the penalty, rather their treatment in the criminal justice system.

Despite the remarkable improvements, some public officials, among others, still treat victims ambivalently. Victims’ rights are not service standards or pious platitudes — they are mandatory entitlements that create obligations for all public officials.

Victims should not be outsiders in our criminal justice system but genuine participants. Victims’ rights are right in a modern ”transformed’ criminal justice system. Such a system should be capable of striking a balance between the interests of the victim, the accused and the state.

Victims must be given a say on decisions that affect them, and for this purpose they should have access to legal counsel.

Opposition to procedural justice is strong, as evident in the last session of our parliament when proposed reforms to strengthen victims’ rights were rejected by the majority.

Four decades ago, the US Supreme Court observed that victims are not a party in the criminal justice system inherited from the British.

But importantly, that court said a parliament could change this — food for thought ahead of an election and a new State Parliament in 2018.

■ MICHAEL O’CONNELL IS SOUTH AUSTRALIA COMMISSIONER FOR VICTIMS’ RIGHTS