Michael McGuire: John Kerr placed more value in protecting the English queen than Australia’s democracy

The Palace Letters show why Australia needs to stop borrowing another country’s head of state as our own, writes Michael McGuire

- Palace letters from John Kerr show Prince Charles was in the loop

- Michael McGuire: Crows problems are not restricted to on the field

- How to get the most from your Advertiser digital subscription

There is something really quite dispiriting about trolling through what have become known as the “palace letters”.

The letters being the correspondence between Australia’s buffoonish former governor-general, John Kerr, and a bloke called Martin Charteris, who was private secretary to the Queen and, as such, one of her main sources of advice.

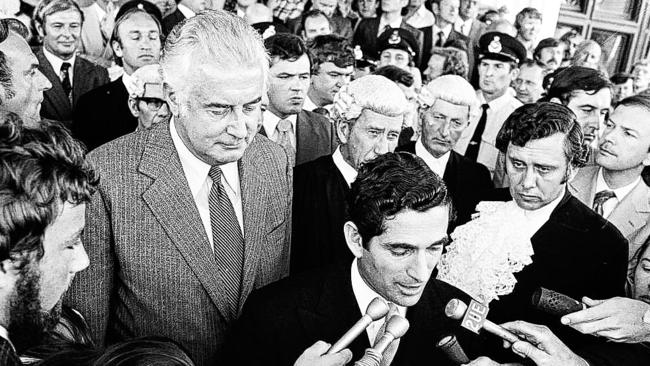

In the letters, Kerr and Charteris spend much time discussing Australia’s developing constitutional crisis of 1975. A crisis that would eventually just be called The Dismissal, when Kerr sacked Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

The depressing, dispiriting side of the correspondence lies in the fact that Kerr, Charteris, Elizabeth Windsor and her son Charles were all involved in conversations about the future of a democratically elected Australian prime minister.

That’s the British monarch, her son, an English public servant and the unelected Kerr all discussing what could happen to Whitlam. But not talking to Whitlam.

Some of the headline reporting on the palace letters has focused on whether Kerr told the Queen he was going to sack Whitlam. Turns out, he didn’t directly.

A decision Kerr made essentially because he placed more value in protecting the English Queen than Australia’s democracy. A decision for which Charteris would later thank him.

But only the most naive and gullible would believe Charteris, and therefore the Queen, did not have some idea of what was in Kerr’s mind at the time.

In one letter, Charteris confirmed to Kerr that the “reserve powers’’ to dissolve parliament did exist.

This is all a long time ago. The fact that it’s taken this long for the letters to be released by the National Archives, and over the continuing objection of the Queen.

They were only released because of the tenacity of historian Jenny Hocking, who argued the case all the way up to the High Court.

But it also illustrates how Australia is still borrowing another country’s head of state.

That is the really dispiriting side of this whole argument.

That, still, after all these years, Australia is apparently not grown up enough to be able to choose its own head of state.

That we don’t have enough intellect, wit or imagination to order our constitutional affairs in such a way as we don’t need to have it all overseen by the Queen of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland. A move towards an Australian republic is being held up by two contrasting forces.

One is obvious enough. Hard-core monarchists. That group of people who don’t believe any of the current 25 million Australians is good enough to be head of state.

Presumably, they believe if the Queen was removed as Australia’s head of state then the country would fall apart.

They should take a look at Britain at the moment.

The Queen is very much still in state over there, yet the nation is falling apart.

It’s almost as if the Queen has no influence over how well, or not, a nation is run.

The other is the republican movement, which for the most part seems to have taken a vow of silence about how it would deliver such a constitutional change.

People need to be persuaded about the benefits of becoming a republic but there is lack of leadership pushing the proposition. A lack of a detailed model about something as basic as how a president would be chosen.

Before the last election, Labor leader Bill Shorten talked about a plebiscite on a republic to gauge public opinion.

It’s probably a decent idea but Shorten would struggle to sell ice to a man dying of thirst in a desert.

A more capable, respected set of voices, that cuts across party lines, is required.

I am an optimist that an Australian republic will be delivered one day. That we will be free to cut the remaining strings to Britain.

That an Australian can be Australia’s head of state. It’s not really that much to hope for, is it?

Then, once that’s done, perhaps we can have that chat about removing another nation’s flag from our own.