Dr Richard Harris quits health for adventure doco making, book writing

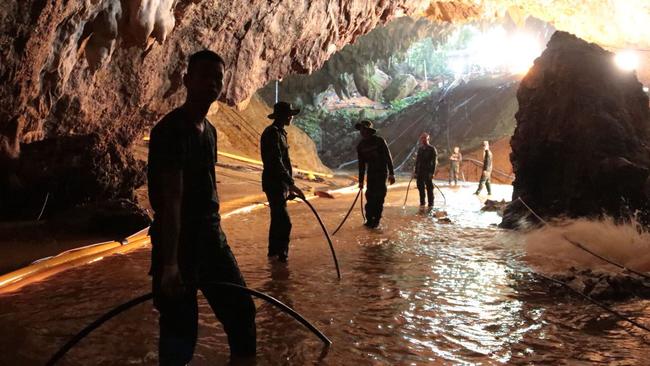

Dr Richard Harris, the humble hero of the extraordinary rescue of 12 young boys and their soccer coach from a Thai cave, tells Jess Adamson it’s time for a new adventure.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

One of Australia’s favourite doctors, Richard Harris, OAM, will complete his last shift as an anaesthetist on Wednesday after 33 years.

And in true “Dr Harry” style, he wanted to go quietly, under the radar, just as he always has.

A humble hero of the extraordinary 2018 rescue of 12 young boys and their soccer coach trapped in a Thai cave, Dr Harris says it’s time for a new chapter.

His life has changed dramatically since the rescue, for which he and his great mate Craig Challen were fittingly crowned joint Australians of the Year.

He’s working on his third and fourth books, is planning to make adventure documentaries and has delivered more than 100 corporate and charity speaking engagements this year alone.

He’s just returned from a week in Boston where he helped deliver a motivational workshop along with some US members of the Thai rescue team.

Not bad for someone who has long been uncomfortable with public speaking. The growing demand for “Harry” has given him the courage to retire from a job he loved.

“It seems really exciting to have a second career at the age of 58,” he says. “I’ve kind of slowly been checking out from medicine physically and mentally for the last couple of years because of all those other opportunities.”

Dr Harris has administered more than 30,000 anaesthetics since his first, under supervision at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, in 1990. Highly regarded by his colleagues, he’s calm, measured and trusted with a kind and often humorous bedside manner.

His patients have included the tiniest of babies right through to a 102-year-old woman.

For a laid-back and self-deprecating adventurer who had planned to be a country GP, it’s been a remarkable clinical career.

“I thought somewhere like Port Lincoln could be the place for me because I grew up camping and exploring on the West Coast. I had in my mind this life of fishing, diving and doctoring,’’ he says.

“And so, Fiona and I went to England in 1991 with the plan that I would do 12 months of anaesthesia and ICU and she would do some emergency medicine.

“I just got the bug – I thought this is actually great, I love it.

“I love the fact that it was very procedural, and it was like physiology and pharmacology in action at the end of the needle.

“If you give a drug and if you give too much you see the result very quickly. It just brought it all to life for me.”

The freedom that came with anaesthesia was also a drawcard.

“If you’re not on call you don’t have any responsibility in the hospital. Unlike a surgeon who might have inpatients for whom they are responsible.

“If I wasn’t on call, I could go away and go diving and I thought, hey this might suit me.”

Amid the pressure of operating theatres, lifelong bonds have been formed.

“Something that’s given me enormous satisfaction is working in private practice with surgeons and nursing staff who’ve become great friends over many years.

“That working relationship actually improves clinical outcomes. It means that if I express some concern my surgeon will immediately say ‘what can we do to make this safer’?

“I’ve made very close friends over the years doing that.”

Among Dr Harris’s career highlights are his work with South Australia’s MedSTAR retrieval service where he thrived in the small but high performing teams, and a two-year stint with AusAID in Vanuatu.

“The Vanuatu experience felt like one of the few times in my life where I can put my hand on my heart and say if I wasn’t there, that patient would have died,” he says.

And so, what does the future look like once the stethoscope is hung up for the last time?

There’s another Alfie the Brave children’s story on the way, along with a book on risk management in the setting of adventuring, to be released next year.

Making documentary films is the ultimate goal and a major deal may not be too far away.

It’s a thrilling next step for someone who carried a camera underwater from the age of 16.

“A friend and I went halves in a small amphibious stills camera when I was at school,’’ he says. “I’ve always been the movie guy for our expeditions and increasingly, I just thought to myself, I’d love to be able to showcase to the world what we see underwater, particularly in caves.

“It seems to be a very, very difficult challenge to get greenlit but I think I’m very close.”

There’ll be time for more cave diving including a return to New Zealand’s Pearse Resurgence with Craig Challen and the pair’s diving mates, affectionately known as the Wetmules. Last time the group visited the cave they reached 245m in an epic dive that lasted 16 hours.

Dr Harris will continue to give back to Operation Flinders and the Kids Foundation, admitting he hadn’t realised how good it is to be a volunteer.

“I don’t believe there’s anything such as true altruism – I get more from helping these kids than they get from me,” he says.

Family is a big priority for the father of three, especially wife Fiona after a series of missed flights from Boston saw him miss her birthday on Saturday.

“She’s amazing. Without her I’d be nothing. She holds the fort, she lets me go mostly,’’ he says.

“It’s incredibly selfish what I do, especially to her, the stress and worry I put her through.

“We’ve been married 32 years and we’re definitely going around for another 30.”

Four and a half years on, Dr Harris is still genuinely surprised at the global attention he’s had since the Tham Luang cave drama unfolded.

Four different films and documentaries have been made about it with Rodger Corser and Joel Edgerton playing our knockabout Aussie doctor in two of them.

Dr Harris is still in contact with the young boys and their families. There’ve been tearful reunions – and he’ll be forever grateful to have played a role, despite having zero confidence they’d make it out alive.

Let’s not forget, as the world watched, he sedated the children with ketamine in a desperate last-ditch attempt to save them, before the rescue team guided them unconscious and underwater through the many chambers of the dark and flooded cave. It was the best of the bad options they had.

“If you asked me tomorrow to do it again, I’d still be very pessimistic about the outcome,’’ he says.

“But I felt so completely privileged to be a part of it. The story of humanity working together is so powerful, it’s amazing.”

In a week where our young school leavers are contemplating their futures, Dr Harris is an inspiration.

He’s not afraid to admit he didn’t fit in at school and wasn’t clear on what he wanted to do.

“I was hopeless at sport. I wasn’t super smart, I had to work to get good grades,” he says.

“I was sort of at the bottom of the top stream, surrounded by people who were smarter than me. It wasn’t good for my confidence and for a while I felt a bit crushed.”

But he worked hard enough to “sneak in” to medical school and while he failed the first year “comprehensively” he made it in the end. His message? Everyone has a unique set of skills. Find them and follow them.

“Not everything comes easily to all of us and sometimes it takes time to find what the right thing for us in life is,’’ he says.

“I’ve probably only realised with this event in Thailand that this unusual set of hobbies and skills that I’ve accumulated suddenly became an important part of who I am.

“If you have something about you that’s a bit different, don’t look at that as a disadvantage – one day you’ll work out that’s going to make you the person for the moment.

“I’ve been so lucky in my life.”

We are the lucky ones. Thank you, Harry. Let the adventures begin.