Christopher Pyne: Very few political pundits were prepared to make a firm prediction

The past few weeks have looked bad for the government but to the people who really matter it will go mostly unnoticed, writes Christopher Pyne.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Having just spent the larger part of the past two weeks in Canberra, I’m reminded why I don’t miss politics.

The hole in the membrane of the Canberra Bubble is that it abhors calm.

The collection of journalists, columnists, MPs, senators, ministers and their myriad staff and hangers-on exist in an atmosphere unlike any other in the nation.

It thrives on crisis.

When politics is dull and boring, the voters like it. But the opposition can’t bear it because it looks like the government is getting on with governing. The press gallery hate it because it gives them much less to report.

Instead, it becomes a vicious cycle of calm, the creation of crisis, the breathless reporting of crisis, the exhaustion of the protagonists and then a return to calm again.

Everyone in the Canberra Bubble professes to be looking forward to Christmas, the new year and summer holidays. I assume they need to recharge their batteries so they can do it all again in 2022.

Election years are the hardest years of all in the political cycle.

There will be a national budget on March 29, followed by an election called for May. I expected and predicted as much.

I never bought into the excitement generated by some in our polity that the election would be at the end of 2021. There’s far too much for the Morrison government to settle, as much as can be settled, around the coronavirus pandemic.

They also will be determined to outline an agenda for what would be a fourth term for the Coalition since the Abbott government was elected in 2013. All of that will take the next six months.

The opposition would like the election yesterday but they don’t get to decide. That is uniquely in the hands of the Prime Minister alone.

This will be a watershed election for the Labor Party. Labor has won only one majority in the House of Representatives since 1996 – the 2007 national election when Kevin Rudd became prime minister.

At the 2019 election, then-opposition leader Bill Shorten had an arguably “big government” agenda, which made it easy for the Coalition to convince the voters to stick “with the devil you know” rather than try Labor’s plan.

Right now, Anthony Albanese’s opposition is adopting a small-target crouching position.

We don’t know very much about the detail of what Labor would do in office. Admittedly, this strategy has worked in the past. But if it doesn’t work this time, many in Labor will question what they have to do to win the trust of the voters.

In 1996, John Howard had offloaded barnacles from the 1993 “Fightback” agenda of John Hewson that was radical, scary and, finally, fatal to Hewson’s chances of becoming prime minister. Howard was small-target to Hewson’s biggest target of all.

The Rudd-led opposition convinced voters that nothing much would change if they were elected, other than the prime minister.

Again, they presented a small target. As Howard had been prime minister for 11½ years by then, the tactic resonated.

The press gallery in Canberra always demand the opposition produce a detailed policy agenda. Once the opposition does so, they then tear it apart as it fills airtime, viewing time and newspapers.

When the election is over, they can then spend time analysing the failure of the opposition to win because they adopted a detailed policy agenda and made themselves sitting ducks for pointed government scare campaigns.

If the opposition doesn’t produce a far-reaching policy prescription, the media herald that they are unprepared for government and need more time to sort out what they stand for. As you can tell, it’s a circular argument.

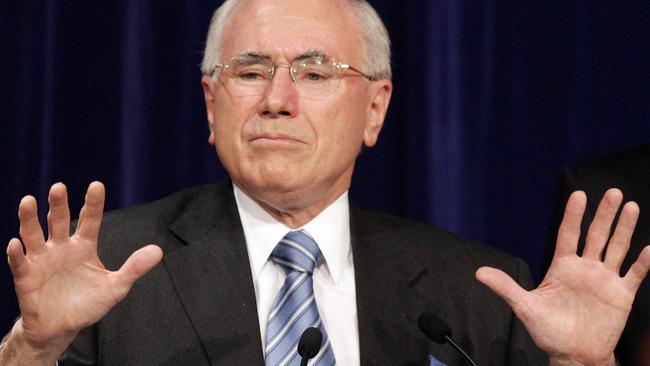

Surprisingly, in Canberra in the past fortnight, despite what looked like a slightly chaotic mess, very few political pundits and former colleagues of mine on both sides of the aisle were prepared to make a firm prediction about the outcome of the next election.

There are too many variables. How will people vote in the midst of a pandemic? Will they mark the Coalition down for their performance on health or will they give them credit?

What effect will fear of a global recession – induced by a sluggish Chinese economy and the impact of the ongoing uncertainty about the pandemic – have on whether voters want to stick with what they have now or risk change?

If they change, will it be to something better? How will the closure of borders affect people’s confidence and thinking?

What will the impact of individual state premiers be on the outcome in each state? What call will people make between Morrison and Albanese for the person they think is best suited to be prime minister?

People just can’t say.

The only certainty is most voters won’t give it much attention until they have to do so.

They are too busy running their own lives to think about politics and government every day.

The only place that happens is in the parliamentary triangle on Capital Hill in Canberra.

What we affectionately call the Canberra Bubble.