Christopher Pyne: Messy week over Religious Discrimination Bill

Prime Minister Scott Morrison won’t want too many other weeks like the one he just experienced before the federal election due later this year, writes Christopher Pyne.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

To understand the circumstances surrounding the attempt to pass the Religious Discrimination Bill in the Australian parliament last week we need to go back much further.

Firstly, to the birth of the Liberal Party in the 1940s, and then to the Abbott and Turnbull governments of 2013 to 2018.

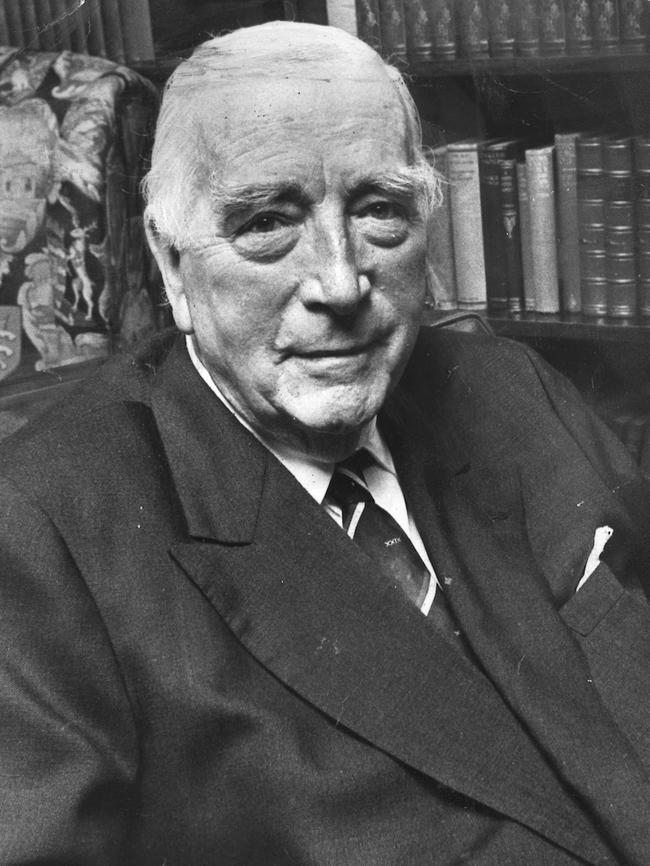

When Sir Robert Menzies created the Liberal Party in 1944, it brought together the liberal and conservative Western political philosophies of the non-Labor side of politics in Australia. Menzies and his team chose the name Liberal because they wanted to be seen to be progressive and in no way reactionary.

In practice, this means that there are members of parliament and senators in Canberra from the Liberal Party that are more towards the political centre, known as moderates, and others who are more towards the right of the political spectrum, the conservatives.

By and large they coexist perfectly happily, and the proof of the pudding has been in the eating, in as much as the non-Labor side of politics has governed for roughly 51 of the 78 years since 1944.

Labor has governed for 27. Voters seem to like the combination.

When the Liberal Party focuses on national security and the economy, it is at its happiest. When it delves into social reform this has historically created tensions.

Addressing social reform is the inevitable outcome of a developing society and it is unavoidable.

Hence a Liberal government is responsible for outcomes such as the ending of the White Australia policy that had entrenched racism in our immigration intake since the early 1900s.

It was a Liberal government, too, that sponsored the referendum that righted some of the wrongs perpetrated against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in the Australian Constitution since Federation.

Fast forward to the Abbott and Turnbull governments of the twenty teens.

In this period, a number of social policy issues arose that created significant tension in society in general, and within the Liberal party room in Canberra specifically.

During the Abbott government, columnist Andrew Bolt was sued under the auspices of section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act.

Putting aside the merits or otherwise of the case, it became a cause célèbre for conservatives to call for section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act to be amended to make its reach narrower.

That did not happen in the Abbott government and the attempt was renewed in the Turnbull government.

In both periods, for various reasons, the attempt to amend section 18C was thwarted. It left a bad taste in the mouth of conservatives.

In 2017, the Turnbull government addressed the issue of marriage equality.

It sponsored a national plebiscite to gauge the view of voters, who were overwhelmingly in favour of reform of the Marriage Act.

In December that year, a private member’s Bill was carried by the parliament that legalised same-sex marriage.

While the sky did not fall in, many conservatives were again unhappy.

During the marriage equality debate, throughout 2018 and in early 2019, a number of controversies were stirred around, among other things, the statements made by the Tasmanian Catholic Bishop Julian Porteous and the celebrated rugby player Israel Folau with respect to marriage and homosexuality.

Bishop Porteous was the subject of legal action and Folau exited rugby for a time and sued his employer.

It’s fair to say that conservatives felt under siege.

Whether they should have felt that way or not is neither here, nor there, they did. Out of that maelstrom emerged the suggestion that the rights of schools, churches and religious groups could be protected through a Religious Discrimination Bill.

Prime Minister Morrison made a promise that he would legislate in this parliament to bring it about.

As we saw last week, that was easier said than done.

There is a danger in believing that you can codify rights. Most of our rights grow out of the progress of the common law – judge-made law based on changing social mores.

When parliaments seek to legislate in this area, they sometimes create more problems than they are trying to solve. Worse, they can actually impede people’s rights, even when they are acting out of good faith.

So, it was that in attempting to codify religious rights through the Religious Discrimination Bill that the debate became less about what the government was trying to do in good faith, and more about the unintended consequences of the legislation.

The government tried to assuage some interested parties’ concerns by moving amendments to another Act – the Sex Discrimination Act.

This only made the matter more complex and open to misinterpretation.

Once the thread had been pulled, the fabric began to unravel in ways that no one could imagine.

In the end, five Liberal members of parliament voted to change the government’s own amendments over the issue of protections for transgender children – something that had not been foreseen when this policy was created three years ago.

It all looked pretty messy, because it was pretty messy.

The Bill has now been sent to committee for further work.

The Coalition government won’t want too many weeks like that again before the election due in May.