’I’m not particularly smart’: Dr Karl shares the secret to his success

He’s the guy on the radio who explains how science works to us ordinary folk, but at one time Dr Karl was digging ditches and had no interest in medicine. He lets us into his colourful home, and fascinating life.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

At 76, Dr Karl Kruszelnicki is still full of wonder.

“Look at this,” he says as he greets me at the door of his house in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, a home as colourful as the man himself with a rainbow splashed across the front wall and a Jolly Roger flag blowing in the sea breeze.

Inside it’s a similar story, with walls of turquoise and pink adorned with stunning artworks, each piece holding a memory for the author and science commentator known to most simply as Dr Karl.

On one of those walls, there’s a portrait of him by artist Peter Pound, submitted for the 2002 Archibald Prize. The good doctor was the subject of five Archibald Prize entries that year – a possible record for the annual award – and has had his likeness painted for it many times since, yet has no idea why some see him as a muse.

Perhaps it’s what’s behind the facade that fascinates artists: a brain that seems to work on overtime and remains as full of inquiry as a toddler with the perennial query “why?”.

On this day, that brain is captivated by a mini printer he’s just brought home from the US: the Zink Zero Ink portable printer.

“Look,” Kruszelnicki urges, opening it up. “It’s got special paper inside with crystals buried in it. These crystals are tautomers – chemical compounds which change from one form to another, in this case when heat is applied. So there’s five layers of paper, including the middle three which change into cyan, magenta and yellow, and can form a rainbow of colours to form the final image.”

He’s already printed out several shots of his family, which includes his beloved wife Dr Mary Dobbie, a son also named Karl, daughters Alice and Lola and two grandchildren.

It’s his family that finally prompted the author of 47 books on science to write his memoir, A Periodic Tale, which is set to be released next month.

“I was very awkward about writing about myself. I found it much easier to write about wonderful discoveries in science and turn them into plain English,” Kruszelnicki says.

“But then, I thought, what if my kids never knew ...”

It’s a question that no doubt comes from experience. In 2019, Kruszelnicki learnt the truth behind his father’s elaborate stories, and his mother’s secrecy, through the SBS program Who Do You Think You Are?

He travelled back to Poland and Ukraine, and what he discovered was chilling. His parents, Rina and Ludwik, were both Holocaust survivors, yet they never shared the true horror of what they faced.

“My father was a journalist and a writer,” Kruszelnicki says. “He did the script for the first Three Musketeers movie in Hollywood and was a scurrilous writer for the Chicago Tribune, so I sort of expected all the stuff he told me would have been exaggerated. In fact it was under-exaggerated. He escaped from death three times.

“Mum was in Auschwitz, yet the way she dealt with it was by lying to me about her age, name, where she was born and her religion, so I grew up thinking she was Swedish and a Lutheran, when in actual fact she was Polish and Jewish and survived years in a Nazi ghetto and concentration camp.

“Later in life, when suffering dementia, Mum did casually drop a terrible hint, saying, ‘I was very lucky to have you because of what they did to me at Auschwitz.’ I still have no idea what she meant, but I know the Nazis did terrible things to women.”

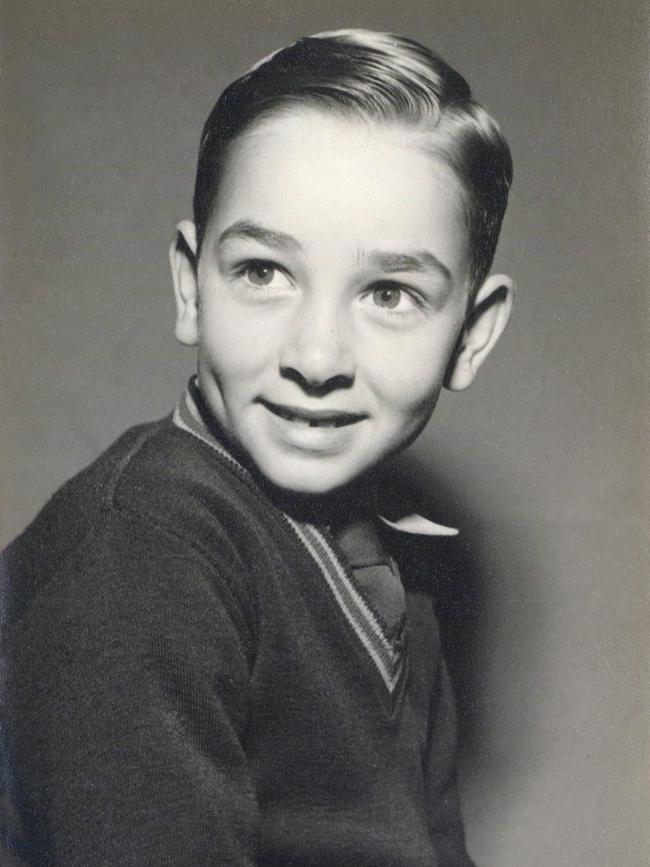

His parents met in a refugee camp in Sweden after World War II, and when their only child, Karl, was two, they moved to Australia, to Wollongong. It was 1950, and while the steel town was built off the back of migrants, it wasn’t such a welcoming place for many of them.

“We were the wogs,” he says. “On one hand the country was overwhelmingly Anglo and we were European, but from the other side of the English Channel, not Mother England, so we were all universally derided.

“I found myself at the bottom of the pile as I was also slightly weird and had different tastes. The Anglo kids liked having white bread, butter and Vegemite sandwiches; I liked black bread with salami and cheese and tomato.

“I even gave up speaking Polish to try and fit in – my father spoke 12 languages, my mother spoke eight and rarely spoke English at home. But we were in a shoe shop in Wollongong and a boy was there from my primary school and his mother pushed him forward and he said, ‘Shut up, you stupid wog, and speak English.’ From that moment – I was about five – I stopped speaking other languages.”

“It isolated me from my parents, as I couldn’t understand what they were saying at the dinner table because I refused to be involved, and it didn’t make me more acceptable to Anglos in any way – they still hated me.”

Yet it didn’t stop him asking questions, with his thirst for knowledge starting at any early age.

Most kids ask questions – “Why is the sky blue?”, “Why is grass green?” – and most are satisfied with a quick answer. Not young Karl.

When Kruszelnicki couldn’t get the answers he was searching for from the adults around him, he turned to books, and found a safe place in Wollongong Library where thre librarians were keen to help this young boy so eager to learn.

“I tried the teachers at school, and they were well-meaning Irish nuns, but they’d not been taught how to educate,” he says.

“So I found my answers in Wollongong Library, and here was a safe place.

“I found myself fascinated reading fairy tales from other countries, and asked the librarians if they had any more.

“They went searching, and two weeks later 200 or so books arrived – one for each country in the world. I just went through them and it was astonishing seeing the similarities and the differences between countries, and it gave me a view from the world, from Zimbabwe to Afghanistan.

“From there it was just a short step to books that made me laugh – and then I discovered science fiction. I began to read science fiction at the rate of one story every day from about the age of 10 to 32. Then I had to stop as I’d started studying medicine and I had so much to study I couldn’t afford to waste an hour a day reading for fun. But I’ve come back to reading science fiction again.”

After high school, Kruszelnicki took full advantage of the free university education available at the time and spent a total of 16 years studying “thanks to a government that believed in the power of education”.

He picked up a Bachelor of Science majoring in physics from the University of Wollongong in 1968; was awarded a Master of Biomedical Engineering from the University of NSW in 1980; and completed his Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degrees at Sydney University in 1986.

Kruszelnicki had done some work digging ditches for the water board, but with his first degree in hand, he joined the Port Kembla steelworks as a physicist, at 19.

His main role was to design a machine to test the fatigue point of steel for use in Melbourne’s West Gate Bridge, which was under construction. But when a supervisor asked him to fake results, Kruszelnicki resigned.

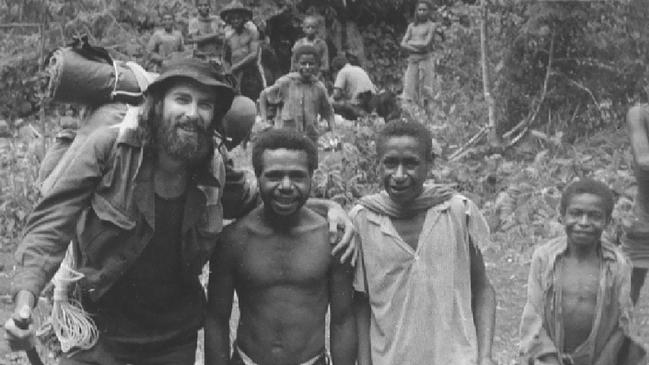

He stood his ground again in his next role, as a tutor at a tertiary college in New Guinea. His manager was undertaking a PhD and wanted Kruszelnicki to not only do all the hard work, but to skew the results. Again, he declined.

From there Kruszelnicki embarked on a colourful array of jobs and lifestyles, from a “drug-crazed hippy” to a taxi driver, filmmaker, roadie for rock and roll bands, a car mechanic and hospital scientific officer.

He learnt much from each role: about the way things worked, about society, about himself. And then, as Kruszelnicki started studying biological engineering, he “fell in love with the human body”.

“Before then I thought the human body was simply filled with a chunky red salsa that might leak if you had an accident,” he says. “I had no idea of the complexity inside; it’s just amazingly sophisticated. I’d spent a lot of my first degree being politically active, but I did really well the second time around at uni, gaining a distinction average.”It was there that Kruszelnicki caught the attention of a pioneering doctor by the name of Fred Hollows, who would become world renowned for his work restoring eyesight for people in Australia and around the world.

“He called me in and asked if I could build a machine to pick up electrical signals off the human retina to diagnose certain eye diseases – mainly retinitis pigmentosa or loss of night vision,” Kruszelnicki says. “That project gave me one of my life-changing moments. Out of the blue a motorbike rider came to us who’d suffered an eye injury after a car tyre threw up a rock which ended up on his eyeball, and his whole cornea was a pulpy mess.

“He could get a cornea from a freshly dead person, but they’re rare, and nobody knew if his retina had been damaged. My machine was the only one at the time that could pick up the electrical signals coming off his retina, and I told him, ‘Hey mate, you’ve got a good retina; they can give you a cornea.’

“Then he said, ‘Can you do the operation?’ and I said ‘No’. He said ‘Why not?’ and I thought ‘Why not? Why don’t I become a medical doctor … okay, I will.’”

That’s why, aged 32, Kruszelnicki started his medical degree, and went on to work at a number of hospitals, including Sydney Children’s Hospital.

He loved his job, but it was confronting at times. Kruszelnicki was there when a child died of whooping cough for the first time in 20 years. He ended up leaving the profession, but the experience taught him vital lessons about the power of vaccines and other advances in medicine.

“We had 15 to 20 years of zero deaths from whooping cough in Australia. I was there at the kids’ hospital when we had the first death in Australia, and the baby didn’t have to die,” he says. “There’s some vaccines like measles that are really effective; if you have one shot you’re then covered for your whole life.

“But the whooping cough vaccine only gives you about 70 per cent protection; the only way it really works is if everyone in the community is vaccinated. That’s why you need herd immunity.” When the Covid pandemic came – and with it a plethora of conspiracy theories and anti-vaxxers – Kruszelnicki again had to battle misinformation around vaccines and science.

“I’ve been vaccinated five times. At the start we knew if we did not have a vaccine and we did not do isolation, the result would be one per cent of the population dead,” he says.

“On average people know 100 people, so if we did nothing, we would all know someone who would die. Luckily we did social isolation until we got the vaccine.”

For Kruszelnicki, it’s a no-brainer, and he credits modern medicine for saving so many lives, including some of those most dear to him.

“My son would have died at the age of six, because a well-meaning friend went overseas and got infected with tuberculosis and came back and gave it to him,” he says. “My daughter Lola had a febrile convulsion at three years old and was paralysed down one side of her body. She was stabbed (with a needle) and given antibiotics and she came good on the tip of a needle. My granddaughter had a fever last Christmas Eve. We took her to hospital and within one hour she had been X-rayed, admitted, stabbed and filled with IV antibiotics, and did not die. Three of my five descendants would be dead if not for modern medicine.”

Another career Kruszelnicki pursued was becoming an astronaut. He even penned a letter to NASA but was told the jobs were for American citizens only. While he didn’t land that job, his fascination with space did lead to the career for which he’s best known: in radio.

“Back in 1981, Triple J was planning to do live coverage on the launch of US Space Shuttle Columbia. It was a big deal. They had to organise audio links from Florida to LA to Honolulu, to Overseas Telecommunications in Sydney and back to the Triple J studio,” Kruszelnicki says.

“Fresh from getting my knock-back from NASA, I rang the station up and offered my services to talk about the space shuttle, and they asked me to come in for a chat, and from there I was invited to cover the launch.

“The launch didn’t go off on the designated date because of a problem with one of the fuel cells. Luckily I knew about fuel cells and was able to explain what happened. Two days later I was back on air for the rescheduled launch.”

Afterwards, Kruszelnicki’s radio career was officially launched, when the producer told him he would be perfect for a show called Great Moments in Science. And the rest is history.

Today he’s kept busy with 10 science shows on ABC radio, as well as frequent appearances on commercial radio and TV. Kruszelnicki still loves opening up the world of science to young and old, and he’s happy if his path to “fame” proves an inspiration to others.

“The biggest thrill I now get in being Dr Karl is being in the supermarket, and someone says ‘Hey, Dr Karl, I’ve been listening to you on radio and now I’m going to … ’, and here they insert any number of things, such as ‘go back to finish my HSC’, ‘start my nursing certificate’, ‘finish off my carpentry trade’.

“I don’t know what it is about being on the radio that encourages people to get another skill, but that gives me such a thrill.”

Kruszelnicki has alwayshad a project or two onthe go on the side – he once won an Ig Nobel award (a satirical science prize) after discovering the mystery behind belly button fluff and why it’s nearly always blue. (Spoiler: It’s a mix of dead skin and fibres of clothing and the average colour of clothing worn in western society is blue). His latest pet project is trying to devise individual, personalised AIs that will be able to engage the many hundreds of people who try to “correct” him on issues from climate change to vaccination on X, formerly Twitter.

“(Twitter) has turned into a battlefield of bots who just try and shout down reasonable people,” Kruszelnicki says. “I use an example from Only Fans. I read an article that said users get a small amount of money from subscriptions; the majority of their income comes from special offers sent out. Subscribers think they’re getting a personal message, but really they’re being sent by people in countries like Venezuela and India. But now those jobs are going to bots.

“So I thought, I’m getting hundreds of people coming at me, I can’t engage each one individually, but if I get a heap of bots as my agents, I can activate them to talk to Fred or Sally or John and so on. But the bots need to psychologically tune to each of them because, for some people, getting told the accurate facts will work, but for others who, say, need to chop down trees to earn money, they might need to think about what that means long term for their children. So responses need to cater for that.”

Kruszelnicki remains in two minds about AI. It can be a help – he uses Chat GPT and Perplexity to look up answers, usually from his own books – but it can’t always be trusted.

“I’ve found 70 per cent of the time my brain is better than Chat GPT and Perplexity; while five per cent of the time they suggest something I’ve forgotten or something I didn’t think of,” he says. “However, 25 per cent of the time they are very confidently wrong.”

Climate change remains a passion for Kruszelnicki, and he’s still banking on renewable energy as our best bet to reverse the damage.

“We can reverse climate change. The basic principle is we do not take any more carbon from underground to the surface,” he says. “The main reason we use oil, gas and coal is for energy and raw materials, but already today we can replace virtually everything we do with raw materials with things from nature. For instance, you can convert wood to make it three times harder than steel and as transparent as glass.

“If whatever carbon we have underground we leave there, the carbon dioxide levels will stabilise and then begin to come down again. The barrier to that, of course, is fossil fuel companies.”

As for nuclear power, there’s a case for, he says, but a stronger case against.

“The science is straightforward,” Kruszelnicki says. “A nuclear reactor itself takes a lot of energy to make but once it’s going it’s very safe.

“But after about 50 years, all the plumbing begins to leak and it’s hideously radioactive.

“So the average reactor takes 15 years to build, you use it for 50 years then abandon it, and it remains radioactive for a quarter of a billion years which puts a huge cost on future generations.”

Of course, he has another solution, and it comes in the form of electric vehicles, which Kruszelnicki says could power houses, streets and whole cities if there were enough of them, and the right infrastructure around them.

“An electric car has a battery with a capacity of 100 kilowatt hours,” he says. “That will run a car for 600km, or you can run an American house for three or four days. Or run my house, which has double glazing and insulation, for about 10 days, or an apartment for 20 days.

“If every car in Australia was an electric car and the grid went down, and you had charging points in every street, then the cars could run the grid for a week. Recently there was a blackout in Yass, and people were running their houses off their electric cars.”

Kruszelnicki is also passionate about improving social justice – something that started in his university years. “The gap between the rich and poor has never been greater in human history,” he says. “Previously the greatest gap was in 1920 and we again reached that around 2015, and now it’s the worst it’s ever been.

“The key is liberating people from what holds them back. I go back to the supermarket, where people tell me they’re getting back to further education or training, and in an unfair world I feel thrilled that they’re discovering a way out, a means to get a higher income.”

Kruszelnicki has had his knock-backs – in addition to NASA’s rejection there was a failed tilt at politics in the 2007 federal election – and he claims that he’s not particularly smart either. What he does have, he says, is the ability to turn complex information into a simple story that’s accessible for everyone.

“Look at humans as a hunting animal; we’re not particularly fast, our claws are not like bears, but we have a brain and can form ourselves into groups and part of that social cohesion is stories,” Kruszelnicki says.

“My real skill is the knack of finding something that the average Australian will find interesting and then I plagiarise it and turn it into English. For instance, it took me 20 hours to understand bitcoin. Now I can recount that in three minutes, so that’s my skill.

“I’m not particularly smart. My IQ is 110. I’ve worked with many smarter people who can get to understand things quicker.

“But by having to understand all the steps in between I can explain it to the general public and it makes sense. In a way, not being that smart has been an advantage.” ■

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki’s memoir, A Periodic Tale, ABC Books, $45, is available for preorder now and in bookstores from September 4.

Orpheum Cinema and Constant Reader Bookshop present an evening with Dr Karl. Tuesday, September 17, 6.30pm. orpheum.com.au

More Coverage

Originally published as ’I’m not particularly smart’: Dr Karl shares the secret to his success