‘Absolutely slower’: The hoops a Sydney Harbour Bridge DA would have to jump through now

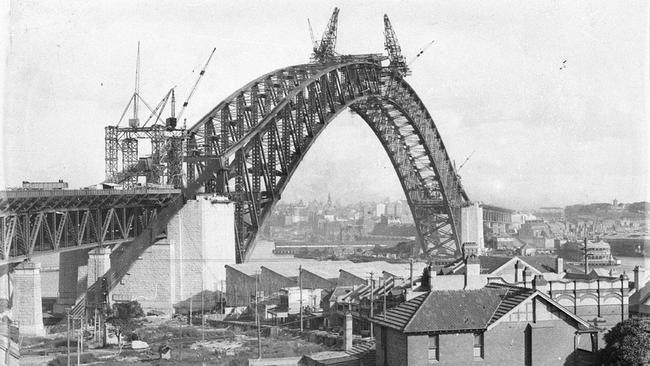

Anyone trying to build a modern-day project akin to the iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge would have to contend with a logjam of environmental and bureaucratic red tape, experts say.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Anyone trying to build a modern-day project akin to the iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge would have to contend with a logjam of environmental and bureaucratic red tape which would have hobbled the original development, experts say.

One of the biggest projects built in Sydney since then – the WestConnex motorway network – showed the length of time mega-projects take now, with more than 11 years passing between the formal concept for the project being lodged in 2012 and the final stage opening.

A new harbour bridge-sized development would likely follow a similar pathway, with an initial concept plan needing to be outlined.

A year after the formal concept for WestConnex was tabled, the initial environmental review for the project was published – the first in a series of reports in environmental impacts.

A project the size of the harbour bridge would likely be tipped into the state significant planning pathway – used for major projects with impacts beyond their local area – which can be approved by the NSW Planning Minister, or a senior planning official.

Some projects can also be deemed critical state significant infrastructure, which can only be approved by the planning minister.

A massive project can also be referred from the state significant development pathway to the NSW independent Planning Commission (IPC), reserved for large-scale project facing significant community opposition.

Even then, with approval, projects can be scuppered – such as a proposed gold mine near Blayney, which was hit with a partial section 10 ban by Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek, despite being approved by the IPC.

One of the masterminds of the Sydney Harbour Tunnel, which opened in 1992, said NSW’s planning system has grown vastly more complex since then.

Tony Shepherd, who was director at Transfield in charge of development when the tunnel was planned and built, said they still had to contend with environmental surveys and other box-ticking exercises when the undersea tunnel was proposed.

“We did an environmental survey (and it) took us about two years all up to do the studies then get the approvals,” he said.

“If you came up … with a new harbour bridge of the size and complexity of the original by John Bradfield … you’d be lucky with all the studies and whatnot you have to do if you could get it (approved) in five years … you’d be doing well.”

He said the NSW planning system desperately needed reform.

“It’s absolutely gotten slower and more difficult to get things through. I believe in good strong planning and environmental assessments – but there’s a limit to how long it’s got to take … my strong recommendation to government is to find a way to streamline it without putting good planning and the environment at risk.”

One thing that hasn’t changed is opponents to progress – with Mr Shepherd saying the tunnel had its share of detractors.

“We had to fight off the NIMBYs, North Sydney council was dead against it … despite it dramatically reducing congestion in North Sydney, and vastly improving the quality of the air there,” he said.

Urban Taskforce CEO Tom Forrest, when asked about the difficulty of building a new Sydney Harbour Bridge-type development, pointed to the near-decade long saga for a bike ramp to be built on the northern side of the bridge.

That project, talked about since the 1980s, had funding announced for it in 2016, before funding was recommitted last year for its construction.

“It’s a great example – to think that has taken so long, and still doesn’t exist,” he said.

“The idea of (now being able to build) a life-changing, city-building piece of core infrastructure (like the Sydney Harbour Bridge) with capacity to cater for the following 100 years is hard to believe.

“There would be any number of potential impacts on flora, fauna, and noise … I’ve got no doubt there’d be some who would oppose the obstruction of the view.”

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘Absolutely slower’: The hoops a Sydney Harbour Bridge DA would have to jump through now